![]()

Chapter 1

A New Chronology and New Agenda: The Problematic Sixth Century

John Hines

The New Chronological Framework for Early Anglo-Saxon England

It is a familiar state of affairs for the positive results of a major research project to pose an entirely new set of questions as the answers to the questions initially addressed. Indeed, it is quite reasonable to expect to assess the success of a programme of research primarily by the character and importance of the further research questions it generates. The results of a thorough review and revision of Early Anglo-Saxon archaeological chronology were published recently (Hines and Bayliss 2013). This report proposed a new chronological framework for the Early Anglo-Saxon archaeological period, now confined within the fifth to seventh centuries AD, with associated calendrical date-estimates for definable phase-boundaries. The chronological scheme and the dates associated with it have wide-ranging implications for cultural history. One of the most unexpected of those is the impact of our new insights upon processes of cultural history in the sixth century AD, a period of time which had not formerly been considered to be much of a problem.

A report that appears in a printed volume of some 600 pages, with several hundred figures and tables, inevitably includes too much in the way of data, analysis and interpretation for introduction in a summary manner. Experience has already taught us how difficult it can be to anticipate what sort of selection or emphasis from this report is most appropriate for different audiences and readerships: a fundamental choice is that between explaining technically and methodologically what was done and explaining as clearly as possible what the results are. The intention in the present paper is not to go over what is already in print; rather it is to focus on one particular context in which these results can be applied. This should serve as an effectively illustrated introduction to both the methods and the conclusions of the chronological analysis, by making the impact of those results particularly clear.

It is important, however, to be clear what the results of the new chronological framework pertain to, and therefore what sort of results we have. The project involved a great deal of interpretative work and evaluative discussion in the process of working between the methods and the results. This was not a set of tasks for which the team simply defined a series of techniques, applied them, and produced some answers. The inter-relationship between different components of the project was always meant to be iterative and cyclical, refining our methods and the organization and selection of data in light of interim results. We also had to solve some purely practical problems which no idealised or theoretical ‘methods statement’ could ever have anticipated (Hines and Bayliss 2013, esp. 89–99). These points are highly relevant to the principal focus of the present paper.

Of no less importance is the fact that this project was not the only piece of research in this field going on at the time. There is a wider context of relevant and complementary investigations. Largely by coincidence, 2013 also saw an analytical and interpretative volume on the massive cremation cemetery at Spong Hill in Norfolk brought together and published. The results of that work were genuinely innovative in that they have now provided us with a very large assemblage of material assigned to the fifth century AD (Hills and Lucy 2013). Only in the few years before that had we seen studies of the archaeology of the fifth century on the Continent and in southern Scandinavia move to a new level of confidence and precision, combined with comprehensiveness, especially through the analyses of the votive deposits at Nydam, southern Jutland, and Kragehul on the island of Fyn, by Andreas Rau and Rasmus Birch Iversen respectively (Rau 2010; Birch Iversen 2010). These showed how those deposits, including some material with very close parallels in England, can be correlated with the scheme of phases defined by Horst Wolfgang Böhme around the Roman Imperial frontier further west and south on the Continent, where calendrical dates can be assigned to the finds through their associations with datable coins (Böhme 1975; 1987).

The Anglo-Saxon chronology project was initially designed and funded by English Heritage as ‘Anglo-Saxon England c. AD 570–720: The Chronological Basis’. The time-span then selected represented in part a particularly favourable segment of the then-available standard radiocarbon calibration curve, although it is evident in fact that this should have been just as effective back to circa AD 530 (Fig. 1.1). Inevitably, the project design was also guided by the understanding of the chronological sequence as it stood in the mid-1990s. That included a belief that the ‘Early Anglo-Saxon’ practice of regular furnished burial continued into the first half of the eighth century, and secondly that there may have been a major material-cultural boundary line in Anglo-Saxon England around AD 570, although this was questioned (Hines 1984, 16–32; Geake 1997, 1, 7–10, 25–26 and 123–125; Brugmann 2004, 42–70). Using translated German and Scandinavian terminology, some of us used to call that boundary-line the ‘end of the Migration Period’: it was a time when a large range of earlier artefact-types went out of use, the frequency of furnished burial appeared to decline markedly, and its geographical distribution also appeared to shift.

Figure 1.1 The radiocarbon calibration curve available at the start of the project ‘Anglo-Saxon England c. AD 570–720: the chronological basis’ in the late 1990s, with the section cal AD 570–720 highlighted and the intercept line between cal AD 530 and the curve marked. Also highlighted is the area of a plateau in the calibration curve from c. cal AD 420–530 within which precise radiocarbon dating is impossible. After Hines and Bayliss 2013, fig. 2.3.

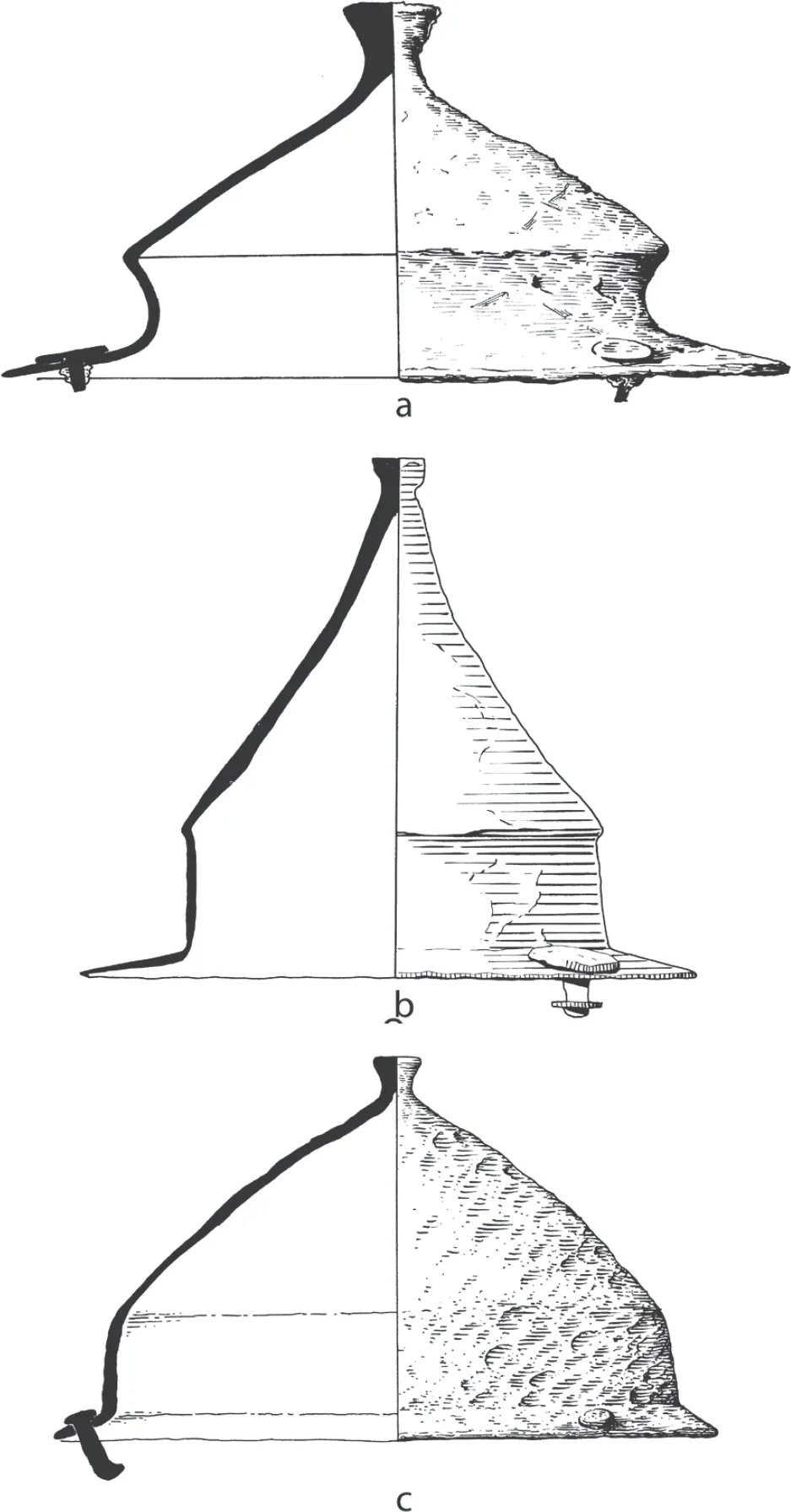

It proved necessary to construct chronological sequences for male and female graves separately. There are too few artefact-types that occur in the burials of both sexes to support a single scheme; especially in the case of artefact-types that are of chronological significance. There are some such objects, such as certain types of buckles or belt-fittings (Fig. 1.2) and of pottery, which allow us to correlate the male and female sequences once they have separately been established (Hines and Bayliss 2013, 473–476); and ultimately the provision of grave goods in both male and female graves came to a single, quite abrupt end. However, the phases within the chronological series are defined quite differently for males and females, and indeed more sub-phases could be identified amongst the men’s graves than amongst the women’s graves within more or less the same period of time.

Figure 1.2 Types of belt-fitting which occur in both male and female graves in Early Anglo-Saxon England. a: strap-end of form BU4-e (Buckland Dover, Kent, grave 98); b: belt-mount of form BU4-d (Bifrons, Kent, grave 43); c: shield-on-tongue buckle of form BU2-d (Buckland Dover, grave 91) (Buckland Dover, Kent, grave 91); d: shoe-shaped belt-mount of form BU2-h. All illustrations from Hines and Bayliss 2013, Chapter 5.

We also found it necessary to extend our analysis back to an earlier point in the archaeological sequence than we had originally intended: in fact, we went back to a point close to the date around AD 530, which it was noted, in respect of the radiocarbon calibration curve (cf. Fig. 1.1), was always going to be a workable parameter to start from. The reason for this, however, was simply that, with the seriation technique being used, we needed to use a longer sequence of change for the series to appear at all. In fact, the extent to which the sequences were extended was done differently between the male and female series. The male sequence actually runs well back into the fifth century. In the case of the women’s graves, however, we could rely upon a study published by Birte Brugmann in 2004 on glass beads from women’s graves in England to go back only to a threshold she labels the start of ‘group A2b’, and dates to c. 530 (Brugmann 2004, 70). In fact, we had access to Dr Brugmann’s work before it was published, and checked her conclusions very carefully. What this means in practice is that in the female series we have only grave-assemblages that include bead-types that did not exist before a certain, well-defined threshold, and so, obviously, cannot be earlier than that boundary-line (Hines and Bayliss 2013, 202–209, 353–364, 372–383). We made no assumptions, however, about what the true date of that threshold was.

In light of these necessary and pragmatic decisions, there is a further important point to be made about the representativity of our data for the earliest parts of the Anglo-Saxon furnished burial sequence. Within the range of dates we were originally meant to analyse, that is from c. AD 570 onwards, our collection of Anglo-Saxon burials is as complete as we could possibly make it — up to the practical cut-off point in January 2005, when it was necessary to proceed to analysis without continually trying to incorporate every new find. In respect of material we would suppose, on the understandings existing when the data collection was undertaken, to pre-date c. AD 570, however, the grave-assemblages and their artefacts we have included are unquestionably just a sample. We consider it to be a good sample, but in particular it is a sample whose quality is to be judged first and foremost by its fitness for its purpose, which was to secure a reliable sequencing for the later finds. This becomes especially relevant when we talk about the relative frequency of furnished burial in various phases. From the late sixth century we can give and compare very reliable figures. Down to around AD 570 we know that more finds have been made which belong to that phase than are included in our data-sets.

What came out of this in the end, then, were separate sequences of male and female burials, ordered by the similarity of their contents. These sequences are divided into chronological phases. We would not realistically expect our methods to have put every individual grave in each of these sequences into a strict, correct, chronological order: in fact we can test that mathematically as well, and the closeness of the male sequence to that ideal is as high as 89%, while that of the female sequence is at best 67% (Hines and Bayliss 2013, 294–295 and 416–422). What therefore we have to do is to see how we can group the grave-assemblages into chronologically distinct phases — a process which actually involves finding chronologically secure boundaries within the series and between burials rather than identifying focal points for clusters of burials. In this way we can identify six phases in the male sequence and five in the intrinsically less precise female sequence. Actually, our procedures allow us to define the six sequential male phases according to two different methods of partition, but really the difference in output between those partitions is not great, and this is not an issue to dwell upon here (see Hines and Bayliss 2013, 251–296 and 459–464).

The present paper refers solely to the mode of partition of the sequences into chronological phases which I believe to be the most practical and most accessible in archaeological terms. This is the phasing of the archaeological sequence based upon leading types. The idea essentially is that a properly defined artefact-type must have a certain starting-point in time — a threshold at which it was first invented or designed and introduced, and before which, of course, it simply did not exist. Chronologically, the most useful artefact-types are those which will define the most precise and narrowly dated series of phases that we can identify. In practice, in the male burial sequence this means successive forms of shield boss, although sword-fittings can be significant too (Figs. 1.3–1.4); in the female burial sequence, as already noted, it involves the successive introduction of new types of bead worn by the women in their necklaces.

Figure 1.3 Leading types for the phases AS-MA to AS-MC in the new chronological framework for Anglo-Saxon graves and grave goods. a: shield boss of Class SB1 (AS-MA); b: shield boss of Class SB2 (AS-MB); c: shield boss of form SB4-b (AS-MC). All illustrations from Hines and Bayliss 2013, Chapter 5.

Not only is there a difference in the number of phases into which we can divide the male and female sequences, but there is also one dramatic difference between the overall profiles of the two sequences through time. What essentially underlies that difference is dramatic variation in the frequency of furnished burial for men and women respectively. With both sexes, we see a very sharp drop in the numbers and frequency of chronologically identifiable furnished burials around AD 570. This was suspected to be the case when the project started; but it was important to confirm it, if possible; and it bears further discussion in culture-historical terms. This decline may have been even more severe amongst the women’s burials than it was amongst the men’s, to the extent that we had seriously to consider the possibility that the practice of burying women with grave goods in England was not in fact continuous from the sixth century to the late seventh. We concluded that the practice did carry on without a break, even if it became quite infrequent (Hines and Bayliss 2013, 339–356). Subsequently, however, a profusion of women’s graves reappears around AD 625/630; at the same time, though, the number of well-furnished men’s graves being buried remains low (Hines and Bayliss 2013, 476–479 and 529–543). Finally, regular furnished burial came to an end for both sexes by about AD 680 (Fig. 1.5). This is both much earlier, and much more abrupt, than had previously been thought (Hines and Bayliss 2013, 464–473). There is, of course, much to discuss about that event — but that is for another time.

Figure 1.4 Leading types for the phases AS-MD to AS-MF in the new chronological framework for Anglo-Saxon graves and grave goods. a: shield boss of form SB4-a (AS-ME); b: shield boss of Class SB5 (AS-MF); c–d: pyramidal sword-button and long bar-shaped sword pommel of forms SW5-b (AS-MD/E) and SW3-b (AS-MD/E/F) respectively. All illustrations from Hines...