![]()

1

‘Goodbye Livia’: Dying in the Roman Home

David Noy

The classic ‘good death’ in Roman literature is that of the emperor Augustus as described by Suetonius (Aug. 99). Augustus was dying at the family home in Nola, in the same room as his father, at an advanced age. He was surrounded by friends and family. He was fully conscious and in command of proceedings, able to worry about his appearance and to come up with some appropriate last words. For the large number of people who were present near the deathbed he recited the end of a Menander play, which simultaneously showed education, mental lucidity and wit (since it asked the audience for applause). He had some personal words for his wife: ‘Livia, live on, mindful of our marriage. Goodbye!’ (one might ask how such a private remark came into the public domain). The ritual of catching the last breath was performed: Suetonius describes it in a slightly unusual way, as dying ‘in Livia’s kisses’ (in osculis Liviae). The death was peaceful and painless, and the sort of death Augustus himself had wished for: Suetonius says that he regularly used the Greek term euthanasia in its original sense of ‘good death’, as something to be hoped for (cf. van Hooff 2004, 976, 981). This was the opposite of the view taken by Julius Caesar who, according to Suetonius (Iul. 87) ‘scorned such a slow sort of death [referring to Cyrus’ last illness as described by Xenophon] and wished for a sudden and quick one for himself’. Caesar’s death fits into the pattern of violent and dramatic ends which receive much attention in Roman literature (discussed in depth by Edwards 2007), but Augustus’ was a more attainable and satisfactory model for people who were not regularly faced with violence. It was also a model which emperors who died peacefully tried to follow (van Hooff 2003, 112–13).

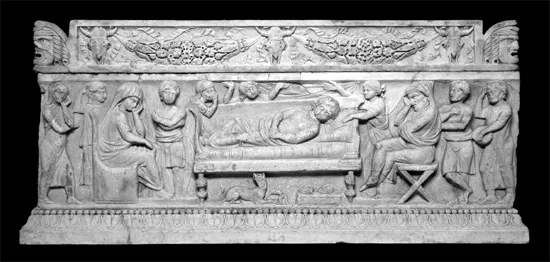

Scenes of peaceful death are not common in Roman art, but they can be found on a number of sarcophagi, and in a few other examples of funerary art, offering a visual equivalent of Suetonius’ literary description. They can represent a mythological death (the favourite being that of Meleager: see LIMC s.v. Meleager; a different sort of allusion to Meleager can be found in one of the monuments discussed by Huskinson in this volume) or a real-life one (usually on a life-cycle sarcophagus; see Huskinson 1996). The dying or deceased person is always young, often a child, and to that extent the art departs from the ideal which Augustus represents. In other respects, the scene emphasises the peaceful and painless death (see also Huskinson, this volume). One such scene is shown in Fig. 1.1. The deceased is shown in a pose which without the context would be hard to distinguish from sleep. The domestic setting is indicated by various artistic details: the bed on which the deceased lies; the slippers and pet dog under the bed. The seated figures in mourning poses at either end of the bed represent the parents, while other female figures make more extravagant gestures of mourning, leading the scene to be labelled a conclamatio (the ritual calling out of the deceased’s name) by Huskinson (1996, 21). The scene is a generic one, found in many slightly different versions, and it emphasises the pathos of the situation as well as the parents’ emotional attachment and the household’s status (Huskinson 2005, 96), but it has a message of consolation too. If a child must die, these are the best circumstances for it to happen in: peacefully, at home and surrounded by family members. With Meleager, where all surviving versions probably derive from one artistic prototype, the death of a hero in his prime can also be read as containing a visual version of the idea sometimes expressed in Roman epitaphs: ‘even Hercules died’. Meleager scenes, although not the deathbed, were sometimes shown with child protagonists, increasing the pathos further (Huskinson 1996, 108–9; 2005, 97). The sarcophagi come from a later period than the literary texts cited so far, primarily the mid-second to early-third centuries AD, but Christian descriptions of idealised death scenes show that many aspects of the ‘good death’ remained unchanged for several centuries, particularly the ‘death as sleep’ motif and the importance of dying at home and/or among family and friends: there are lengthy examples in descriptions of the deaths of Monica (Augustine, Conf. 9.11–12) and Paula (Jerome, Ep. 108.28–30).

Fig. 1.1. Child’s deathbed scene on a sarcophagus (British Museum, GR 1805.7-3.144). Photograph ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

The domestic setting of these idealised deaths will be the focus of this paper. The way in which someone died was important to how they were remembered, which is why imperial biographies tend to give emperors ‘appropriate’ deaths. It was also important to the mourners, whose capacity to perform their role in full was greatly enhanced if the death took place at home with due preparation, and with appropriate ceremony afterwards. Nowadays, dying in familiar surroundings is usually presented as the opposite of a lonely death in hospital. For a Roman, the alternative to dying at home was often envisaged, especially in poetry, as a lonely death abroad, perhaps in exile. Fear of such a death is expressed in literature of all genres, as either a theoretical possibility or, as it was for Ovid, a real issue (Tr. 3.3.37–51, tr. P. Green):

….. Far off, then, my imminent dissolution,

on an unknown shore, a fate made desolate

by its very setting. I’ll languish on no familiar deathbed,

have none to weep for me in the grave; no tears

dropped on my face by my lady who will bring my spirit

a brief reprieve. I’ll have no last words [nec mandata dabo], there’ll be

no loving hand to close my fluttering eyelids,

no final lamentation [clamore supremo]. I shall lie

sans funeral rites, sans tomb, unmourned, unhonoured,

in a barbarian land. When you hear this

surely your heart will be stirred to its depths, and surely

you’ll strike your loyal breast with timid hand?

Surely you’ll throw out your arms in furious frustration

towards this place, clamour [clamabis] your wretched man’s

name in the void? Yet don’t rip your cheeks, don’t tear your hair out…

As with much Latin poetry concerning death and mourning (on which, see Houghton, this volume), this is effectively a description of what normally happened, at least (as Houghton shows) within the elegists’ somewhat unrealistic world, written in terms of what the poet does not expect for himself. Ovid lists many deathbed rites which are familiar from literature or art: the closest relative being at the bedside and closing the eyes; the conclamatio around the corpse; dramatic female mourning gestures after the death (the same details are described by Lucan, B.C. 2.21–6; see Šterbenc Erker, this volume, on such rites). His point is to emphasise the distress caused to him by the fear that he will not receive such care and consolation. Failure to be present at the death would be seen as an additional grief for the bereaved too. Ovid imagines his wife performing a long-distance conclamatio as she will be unable to carry out the normal one by the laid-out body. Dying ‘on an unknown shore’ was a frightening prospect and in this case an exacerbation of Ovid’s already severe punishment.

Apart from psychological considerations, there were also practical reasons why an ideal Roman death involved being at home with friends and family. Ovid’s fear of lacking a funeral and tomb expresses part of this, and other things were also expected to happen before or after death which required the right setting and the right people. Three aspects of this will be discussed here, as illustrations of the usually unspoken reasons why death at home was so important to the Romans: final requests by the dying person; the making of the death-mask; the correct disposal of the body. The first two of these have not received much attention in English-language scholarship. All three, when studied in detail and in conjunction with each other, with the anecdotal literary evidence and scattered archaeological finds placed in context, can offer insight into a variety of ways in which the Roman dead were remembered and mourned.

Final requests

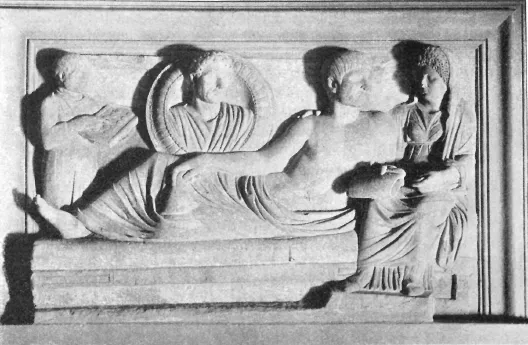

The so-called Testamentum Relief in the Capitoline Museum (Fig. 1.2), which is studied in detail by d’Ambra (1995), depicts an imaginative death scene, full of symbolism rather than the apparent realism of some of the sarcophagi (see also Huskinson, this volume; Hope, this volume). Its original context is unknown and there is no accompanying inscription, but it was probably displayed on the façade of a tomb (Koortbojian 2005, 291). It can be dated by the hairstyles to the time of Trajan, making it earlier than the sarcophagi mentioned above.

The central figure is a young man shown in a heroic semi-nude pose. He is not represented as dying in the normal way, as if sleeping, but the context makes it fairly clear that he is the deceased in the tomb, shown in his home surroundings. D’Ambra thinks that the bed on which he reclines alludes to the bier on which the corpse would be carried in the funeral procession, but it could also be seen as the about-tobe deathbed. It symbolises peaceful and domestic death as on the sarcophagi, alluding to the ‘death as sleep’ motif which could not be depicted here because of the activities which are shown as taking place.

Fig. 1.2. The Testamentum Relief (Capitoline Museum, Rome). Altmann 1905, fig. 161.

In his right hand he holds something which has been restored as a purse, although it is unclear if that is what was originally there. In his left hand he has a partly unrolled scroll. This has usually been interpreted as his will (hence the name by which the relief is known), but d’Ambra notes that wills are normally envisaged as tablets rather than scrolls, and suggests that it could be more generally symbolic of literacy or the authority of written documents. To the right is a seated female figure with a veiled head, whose pose is suggestive of mourning since it is similar to the mothers’ on the deathbed sarcophagi, although at the same time she has a hand on the young man’s shoulder as a gesture of consolation. D’Ambra identifies her as the mother, and this seems much more likely than a wife, especially as a mother at the end of the bed became conventional in deathbed scenes on sarcophagi. Showing the dying man on a bed, with personal possessions in his hands and with his mother beside him, provides visual cues for the viewer to imagine the death as taking place at home.

Behind the bed, a man is represented as an imago clipeata, showing that he is already dead, and he can safely be taken as the father (the young man would not normally be able to make a will if his father was still alive). The imago perhaps suggests the commemoration of the ancestors in the atrium of an aristocratic home (Polybius 6.53); according to the Elder Pliny (HN 35.2.6) imagines clipeatae displayed high on the wall had replaced the traditional ancestor-masks by his time (discussed below; cf. Flower 1996, 41–2). It also shows continued links between the living and the dead, with the deceased father literally watching over his family (Koortbojian 2005, 291–3; Hope, this volume). D’Ambra suggests that the family were ex-slaves and so had no more images to display. Artistic practicalities may also have been a consideration: the sculptor could hardly depict cupboards full of ancestral images as described by Pliny. In either case, there is a clear implication that the events are taking place in the family home under the posthumously watchful gaze of at least one ancestor.

The other figure is a small slave holding an abacus. This must be another allusion to wealth, and to being in control of one’s affairs at the last, as a dying person was expected to be in a good death. The document is not shown rolled up as a scroll normally would be, but loosely folded to indicate that it has recently been opened, before the young man hands it over to his mother. The abacus and the document together suggest that suitable arrangements were being made for his estate before his death.

Romans normally made their wills well before death, but the deathbed codicil was common, and in some cases the whole will might be remade (Champlin 1991, 69). Appian (B Civ. 1.105) has an anecdote about how Sulla dreamed his death was imminent, made his will the next day and died that evening. Sulla can hardly have been without a will previously, so this must be a case of remaking it. Appian notes it as something exceptional that the will-making was completed in one day, and clearly the will of a wealthy Roman was not normally dealt with in a hurry. Apart from anything else, seven witnesses had to be invited, and various references suggest that it could turn into a social occasion, although not an event of great solemnity since remaking the will was so common (Champlin 1991, 76). The dying person could also give a specific verbal instruction, such as this one described by Cicero (Fin. 2.58) which must be a way round the Lex Voconia which prevented the richest people from nominating women as their heirs:

If a dying friend asked you to give back his estate to his daughter, but did not write it down anywhere as Fadius wrote it, nor mention it to anyone else, what will you do? Of course you will give it back. Epicurus himself would perhaps have given it back, as did Sex. Peducaeus… Although no-one knew that he had been asked to do so by C. Plotius, a distinguished eques from Nursium, he came of his own accord to the woman, explained the man’s instruction to her although she knew nothing, and gave back the estate.

This seems to assume intimate deathbed conversations with close friends, a role given to Livia in the description of Augustus’ death. Plotius had a specific reason for making verbal instructions – he wanted to do something which was illegal in a written will – but the principle of last-minute changes was a common enough one, and there are many legal texts discussing complications which might arise. Reading the will before the funeral (e.g. Dio 56.32–3 on Augustus’ will) was necessary because arrangements about the funeral might be specified, and in particular slaves might be manumitted precisely to give them a role in the funeral (see Carroll, this volume).

Other arrangements which did not involve altering the will could be made, and these are occasionally recorded in epitaphs. P. Manlius Syrus appears to have given deathbed instructions to his heirs for an annual rose-scattering and feast at the tomb of himself and his wife (AE 1991, 805). M. Ulpius Philotas, an imperial freedman, gave instructions about his tomb which his wife duly carried out (CIL VI 8553). Both men are described as dying (moriens) when they made these arrangements. Someone with dependants might commend them to the protection of friends or relatives (e.g. Propertius 4.11.73; Cicero, Verr. 2.1.152), or of the army if it was an emperor dying (Dio, Ep. 72.34.1; Lactantius, De mort. pers. 24). The Younger Pliny (Ep. 2.20.5) mentions how the dying Verania cursed the wickedness of Regulus for swearing a false oath to her – the opposite of the more usual commendatio. Such statements, as well as more usual last words like those attributed to Augustus, obviously assumed that someone was going to be there to hear them and write them down or act upon them. The Testamentum Relief indicates in various ways that deathbed arrangements are being made, even if the exact nature of the arrangements is unclear.

Seneca advises that you should finish your life like a fabula: ‘tantum bonam clausulam impone’ (Ep. 77.20). Connors (1994, 228) shows that a clausula in this context could be the end of an extended text (such as a play or a poem), often with a witty or memorable twist, or the final syllables in an artfully constructed sentence. In either case, the instruction c...