![]()

1

The Country and the City

Social Melodrama and the Symptoms of Authoritarian Rule

One of the most accomplished works of the new cinema that emerged in the Philippines in the early 1970s revolves around a scene of waiting, one in which little appears to be happening even though everything is actually at stake. The film, called Maynila: Sa mga kuko ng liwanag (Manila in the Claws of Light, 1975), returns intermittently to the image of a young man standing on a dingy corner of Chinatown. He has his eye on the window above an always-closed storefront. He waits for any signs of his lost sweetheart, a country lass who may have fallen prey to white slavery. Somewhere behind him, a fortune teller’s sign reads: “Do you have a problem?” In an inconspicuous but visible corner of the movie screen, we might find the answer to that question. A snip of graffiti scrawled in blood-red paint on newsprint screams “Long Live the Workers!” Another handmade poster contains an image of a raised fist and the initials of a radical youth organization called Kabataang Makabayan (Nationalist Youth). A third poster, partially torn, alternately suggests the words Junk (Ibasura) and Take Down (Ibagsak), depending on which letters the man’s body obscures and reveals as he moves around.

The political graffiti in Brocka’s mise-en-scène are imprints of history. They are the traces of a political ferment that began in the West—in the antiestablishment and antiwar uprisings of the late 1960s—and spread, albeit not unchanged, to the third world country where the young man dwells. The First Quarter Storm was the name of the biggest salvo of the Philippine rebellion against “imperialism, feudalism, fascism” in the year 1970.1 From January to April, thousands of angry college students, laborers, and political activists took to the streets to express displeasure at the reelection of President Ferdinand Marcos and to demand change in the country. They turned out in droves for the first state-of-the-nation address of his second term and hurled rocks at the first couple as they exited the Congressional building.2 The first lady bumped her head as she scurried into a car. Four days later, activists rammed a fire truck into one of the gates of Malacañang, the chief executive’s residence.3 Authorities went after protesters with batons, tear gas, and truncheons. Often, the youthful activists evaded capture with the help of Manila’s sympathetic denizens, who popped open a door and pulled them in just seconds before the police turned a corner. Some of those events happened on the same streets where the film takes place. Yet in Brocka’s movie, the images of this tumultuous period appear only in flashes, like the antiestablishment slogans glimpsed fleetingly behind the protagonist in the opening sequence.

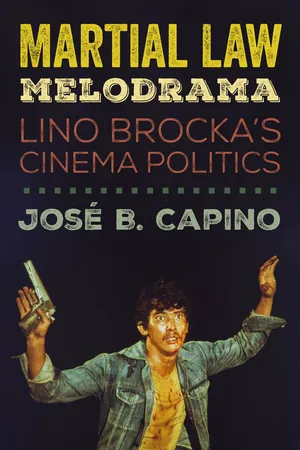

FIGURE 1.1. Posters from the political left loom behind Julio (Bembol Roco) in the opening sequence of Manila in the Claws of Light (Cinema Artists, 1975).

In this and other chapters of the book, I venture a practice of closely reading such provocative inscriptions of politics and history in Brocka’s martial law melodramas. The strict and inconsistent censorship of films during the Marcos regime demands that scholars pay attention to seemingly insignificant details. Such careful scrutiny is also necessary because of the abundance of both thinly veiled and subconsciously inscribed allegories in the director’s work. As I hope to illustrate in this chapter, martial law melodramas follow a tradition of sociopolitical critique initiated in nineteenth-century Philippine letters. That tradition inscribes sociopolitical discourse overtly (through historical and political references) as well as indirectly (through allusions and metaphors). Central to it is the novel Noli me tangere (1887) by Philippine national hero José Rizal. Rizal’s roman à clef inspired a nineteenth-century anti-colonial revolution against Spain.

Before I interpret Brocka’s Marcos-era films through the prism of a critique inspired by Rizal, I wish to discuss the context in which his oeuvre emerged. The director articulated his desire to create a new kind of Filipino film in 1974, two years into martial law and the same number of years after he returned from a self-imposed hiatus from the film industry. Brocka’s star was still on the rise when he took leave from filmmaking. He had directed nine genre pictures, six of them for an independent production outfit called LEA Productions. Several of his movies were box office successes, including his debut, Wanted: Perfect Mother (1970). His work also collected trophies for Best Picture and Best Director at awards ceremonies. Perhaps most notably, critics lauded Tubog sa ginto (Gold Plated, 1971) for its candid portrayal of homosexuality. Even the mediocre Cadena de amor (Chain of Love, 1971)—a romance that shows the leading man walking away from a small plane crash with only a reversible case of amnesia—took home seven prizes from the Manila Film Festival.4 His career hit a low point with two commercial efforts that opened to scathing reviews: Now (1971), a youth-oriented musical with a subplot about political activism, and Cherry Blossoms (1972), a romance filmed partly in Japan and featuring American actor Nicholas Hammond.5 Brocka shared the critics’ poor opinion of his pictures and even told journalists to skip them.6

Brocka declined to explain his respite from the movies, claiming that his reasons were “personal.”7 One journalist speculated that a spat with LEA Productions prompted the hiatus. Rumors circulated that one of the outfit’s proprietors bore a personal grudge against a star in Gold Plated and thus barred its exhibition at the Venice Film Festival.8 Whatever the reason, Brocka diverted his energies to making quality television drama with members of the progressive-leaning theater group Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA), which he joined in the late 1960s. He also planned his eventual return to filmmaking by trying to secure financing for a movie that would take Philippine cinema in a new direction. But, as the director would later recall, he came up empty-handed. “I wanted to work, but producers could not understand my desire to make films that can truly be considered meaningful [may kahulugan],” he told a reporter.9 “Most of the producers that came to me wanted only action or fantasy movies.” One of the board members of PETA created a scheme to fund the filmmaker’s dream project. With the help of investors from the corporate world, the public sector, as well as film actors and creative personnel, Brocka scraped together enough money to found an outfit called CineManila. According to press releases, the company aimed to produce films “with a good story, good cast, that depicts Filipino values so that audiences can identify with them.”10 Brocka also expressed his desire to make “a complete breakaway from the trend for fantasies and slapstick comedy” that ruled popular cinema.11 CineManila envisioned a transnational audience for its alternative pictures, identifying “Guam, Hawaii, Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan and California” as prospective markets because of their large overseas Filipino population.12

A project initially called Buhay (Life) served as the test case for Brocka’s new cinema. Mario O’Hara wrote the screenplay, based in part upon stories from Brocka’s youth.13 The filmmakers changed the title to Tinimbang ka ngunit kulang (Weighed but Found Wanting), based upon a line from the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament. To obtain lush, bucolic scenery, Brocka filmed on location. As an article notes, he and cinematographer Joe Batac captured the rustic charm of the “hillsides of Tanay (Rizal), the heart of Sta. Rita (Pampanga), the pace and pulse of San Jose (Nueva Ecija) and the beautiful beaches of Nasugbu (Batangas).”14 Brocka made his “dream project” with a shooting ratio of 4:1, considerably exceeding his usually slim allocation of film stock.15

The director remarked to a journalist that the film “is quite timely” (“medyo ayon sa takbo ng panahon natin sa kasalukuyan.”) Quite tellingly, however, Brocka added in Filipino: “But it has nothing to do with Martial Law” (“Pero walang kinalaman dito ang Martial Law.”)16 Fear of drawing the censors’ attention seems to underpin Brocka’s equivocation. This attempt to downplay the film’s political relevance was a calculated gambit. There would have been no means for Brocka’s cinema politics to do its proper work if the censors blocked the film. Indeed, he took pains to avoid shaping the movie around resolute political statements. Only brief instances occur in the film that signal any link to martial law or Ferdinand Marcos. Set alongside these politically charged fragments, Brocka’s insistence on de-politicizing his work generates a curious irony. The conscious erasure of the political all the more registers the moments when, however briefly, it becomes perceptible. The method I propose for reading the films in this chapter, hence, is that of seizing these moments as the distinct allegorical shards of sociopolitical critique.

Beginning with Weighed, Brocka devised a model for an alternative kind of sociopolitical representation on film. Focusing on Brocka’s newly developed filmmaking, this chapter analyzes two landmark works in this vein. Weighed and Manila fall under the rubric of “social melodrama.” John G. Cawleti characterizes the social melodrama as “an evolving complex of formulas” that tell intricate narratives of heightened feeling and moral dilemmas “with something that passes for a realistic social or historical setting.”17 Its purpose, he argues, is to give viewers a “detailed, intimate, and realistic analysis of major social or historical phenomena.”18 Cawleti’s term is especially useful in describing the two Brocka films, both of which combine realism with the sensibility and features of melodrama but also differ from each other in several respects. Equally important, as I have mentioned earlier, the films draw from strategies of representation and critique that Rizal popularized. As in the latter’s novel, the director’s new social melodramas feature sprawling multicharacter narratives with a young male protagonist at their center. Whereas Rizal’s Noli represented the conditions of Spain’s decaying empire, Brocka’s movies registered the state of affairs in the country and the city during the early years of martial law. In the balance of this section, I shall elucidate the workings of Brocka’s social melodramas, trace their connections to Rizal’s example, and map the relationship of his two most pioneering films to the politics of the Marcos regime.

WEIGHED BUT FOUND WANTING

After the cultural and political upheavals of the late 1960s and early 1970s, it might seem odd that Brocka looked back to Rizal’s canonical nineteenth-century fiction in his attempt at devising a novel approach to Philippine cinema. That said, the national hero never lost his appeal to Filipino artists and intellectuals in search of social relevance. To cite just a few examples from the same decades, characters and subplots from Rizal’s fiction inspired such landmark works of Philippine literature as Rogelio Sicat’s short story “Old Selo” (“Tata Selo,” 1962) and Paul Dumol’s play Barrio Captain Tales (Kabesang Tales, 1975).19 Rizal’s influence on critical literature and the arts solidified many decades earlier. As Soledad Reyes notes, the pioneers of the twentieth-century Tagalog novel used his work as “the main sources not only of the realistic tradition but even as sources of realist techniques.”20 They emulated as well Rizal’s project of using literature to engender social reform or, as he put it eloquently, “to expose the cancer of the body politic on the steps of the temple so that a cure may be offered.”21

The influence of Rizal’s vision of art and politics continued to spread with the help of legislation. Starting in the 1950s, the law mandated all Philippine schools to teach Rizal’s writings, thereby informing the vision of artists of diverse political persuasions and various media. Philippine cinema from the start has celebrated Rizal’s works and the hero himself. Its pioneers chose him as the subject of the first Philippine-produced movies. In the 1950s and ’60s, the justly renowned Gerardo De Leon made film adaptations of Rizal’s novels. De Leon was Brocka’s idol, and it seems possible that his work inspired the latter’s fascination with the national hero’s legacy.

The influence of Riza’s Noli on Brocka’s Weighed is evident not only in the latter’s approach to social criticism but also its narrative. Both stories begin with the young upper-class male protagonist trying to find his bearings in his provincial domicile. In Noli, Crisostomo Ibarra returns to the fictive town of San Diego (in Rizal’s home province of Laguna) after seven years of studying and living in Europe. His homecoming is an unhappy occasion. He discovers that his father Don Rafael, one of the wealthiest men in town, died in prison after falling out with a Spanish priest named Damaso. In the Spanish-colonized Philippines, peninsular clergy such as Damaso were virtual sovereigns, more powerful and despotic than colonial administrators. Crisostomo eventually learns that Damaso not only put Rafael in jail but ordered the desecration of his corpse. Damaso’s crusade against the Ibarras continues with his attempts to break up Crisostomo’s engagement to his chil...