![]()

Part I

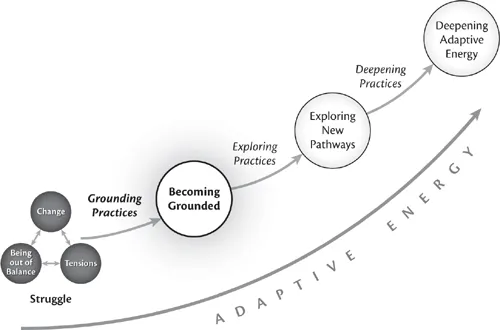

Becoming Grounded

GROUNDING PRACTICES

Adopt a Growth Mind-Set

Become Resilient in the Face of Failure

Draw Your Tension Map

Center Your Mind, Body, and Spirit

Find the Support You Need

![]()

1

Struggle Is Not a Four-Letter Word

Heaven knows we need never be ashamed of our tears, for

they are rain upon the blinding dust of earth, overlying our

hard hearts. I was better after I had cried, than before—more

sorry, more aware of my own ingratitude, more gentle.

—Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

RITA MARSHALL’S TALENTS FOR CRAFTING GREAT PUBLIC RELAtions (PR) campaigns propelled her into a managerial position by the age of 30. Soon after arriving at her new company, she encountered her first leadership struggle.

Marshall was working as a PR professional in an advertising agency. The two disciplines—advertising and public relations—are very different, with dissimilar business models, nomenclatures, and rhythms for engaging with clients. Before she stepped into a formal leadership role, these differences, while minor annoyances, had not directly concerned her. With her new responsibilities, however, came new pressures. Now she had to find a way to make her company’s advertising-oriented policies relevant and meaningful to her PR team, all the while motivating them to achieve results. She found it especially challenging to be working with different players, customs, and rules.

During our interview Marshall told me: “I was tasked with being a leader to grow this division, and yet we had an Excel grid to track projects and progress and touch points that didn’t even match up to the types of projects and deliverables that we had on the other side of the business. Even the words were different. You want your team focused on the work and the deliverables for the client, and yet they were getting caught up in internal details for administering the business.”

Greatly outnumbered, and with an advertising-oriented boss who had a different view of public relations, Marshall started to feel disillusioned and alone. Her boss began to cast doubt on her leadership, which caused her to doubt herself: “There was a point where I just thought, Maybe I’m crazy. Maybe I don’t know what I’m doing. Maybe they shouldn’t put me out there in front of clients. I guess I just don’t have it. And that’s a very frustrating thing when you’re trying to lead, when you have self-doubts and your team is looking to you.”

Marshall’s self-doubts made matters worse. She found it difficult to lead with conviction and became frustrated with a culture that seemed to be blocking her progress. She had to do something. But what?

The Paradox of the Positive

Over the past several decades, the positive psychology movement has gained considerable momentum. It cascades into all areas of life—at work, with friends, in the community—subtly (and at times not so subtly), nudging a positive spin. All in all this is a good thing. Positive energy begets more positive energy. And numerous psychological studies show that when people feel optimistic and confident, they approach life with more vigor, have more-pleasant relationships, and are just plain happier.

Yet the full-throated emphasis on the positive comes at a price. The way that many organizational cultures internalize the principles of positive psychology actually undermines the very intentions of the movement. Indeed, positive psychology does not advocate ignoring the daunting life challenges that other branches of psychology attempt to treat; it is simply a call to pay as much attention to strengths as psychologists have historically given to weaknesses. This “be positive at all costs” misinterpretation can trigger unintentional consequences as it seeps into the cultural bloodstream. For instance, tuning out all negative thoughts and emotions can be a roadblock to the honest conversations people need to have with themselves and with others.

The parallels between cultural attitudes toward positivity and the view of struggle are striking. Like anything other than perpetual cheerfulness, struggle is commonly seen as a sign of weakness, a notion reinforced through a labyrinth of implicit messages. Many leaders unconsciously categorize the word struggle as negative and off-putting, a taboo, which makes dealing with struggle even more difficult than it needs to be.

This can become especially problematic when leaders find themselves facing significant challenges. When external pressures for positive spin create dissonance with reality, leaders may ignore the incongruity they feel in their guts and stifle the candid conversations that could guide them forward. They may unconsciously compare themselves with others and allow this comparison to diminish their self-image and curb their potential. They may fall into the trap of thinking that leaders are supposed to be perfect—or at least perfectly capable of dealing with struggle. Consequently, they can feel embarrassed and stigmatized, thinking, Something must be wrong with me. I’m not like all the other successful leaders out there.

But of course no leader is perfect. All human beings have their own unique flaws and frailties. And of course struggle is a natural part of leadership. Dick Schulze, founder and former CEO of consumer electronics giant Best Buy, who built the company to more than $50 billion in sales with over 180,000 employees, said it best when he told me: “I don’t think that there has been a year in my 45 with the company that hasn’t been beset with struggle.”

Schulze then added:

With every episode of struggle, there is a learning opportunity.

Resolving the Paradox

The solution to the positivity paradox is relatively simple, but it demands a leap of faith. Instead of denying struggle, or feeling some degree of shame, savvy leaders embrace struggle as an opportunity for growth and learning, as an art to be mastered. They come to see struggle as a universal rite of passage without allowing themselves to become mired in it. They trust that engaging earnestly with struggle will ultimately take them to a better place, heightening their awareness of themselves and others and opening their minds to possibilities they may not have otherwise imagined.

Examples abound of prominent leaders who fail in a specific pursuit but who emerge stronger and more resilient from the experience. Had it not been for President John F. Kennedy’s failure in the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, he might not have gained the wisdom needed to meet the greatest challenge of his presidency 18 months later: the Cuban Missile Crisis, which imperiled the very survival of the human race.

Clearly, struggle and leadership are intertwined. Teaming the courage to confront conflict with openness to new learning and the energy of positive thinking can turn struggle into transformation, paving the way for accelerated growth and development. The more that leaders move away from negative stereotypes and welcome a new relationship with struggle, the more they leave room for new possibilities to emerge. They begin asking better questions and recognizing the positive aspects of struggle. Shedding old assumptions, they free themselves to engage differently with the world around them, shaping their conversations to be more open and adaptive.

Two Stories of Struggle

Allow me to introduce you to two remarkable leaders whose struggle stories are vastly different. One was thrust into a top leadership job during a time of crisis; the other strove to fulfill a vision so ambitious and far-reaching that it seemed beyond the scope of human achievement.

Anne Mulcahy

In 2008 Anne Mulcahy was named CEO of the Year by Chief Executive magazine for her work at Xerox Corporation. Eight years earlier few would have predicted it.

In May 2000 Xerox was in turmoil. The board had abruptly fired G. Richard Thoman as CEO after a very brief tenure and brought back his predecessor, Paul Allaire, who personally recruited Mulcahy as president/chief operating officer (COO). By October, Mulcahy began to understand just how bad things were. Third-quarter earnings had missed analysts’ expectations, and the company was close to declaring bankruptcy. Mulcahy candidly remarked on an October 3 investor conference call, “Xerox’s business model is unsustainable.” That simple comment sent the stock price nose-diving and set the stage for an extraordinary story of leadership growth and corporate transformation.

Shortly after that conference call, Mulcahy needed to make one of the most important decisions of her career: whether to seek bankruptcy protection or try to reverse the hemorrhaging of cash that was pushing the company close to insolvency. The company’s financial advisers strongly recommended the bankruptcy route, but Mulcahy had a different vision. She felt bankruptcy would tarnish the reputation of the venerable company she had come to dearly love over her 25 years of employment there.

Instead, Mulcahy set the company down a path of pruning expenses and selling off business units, all the while preserving core assets essential to the rebuilding efforts. One of the core assets she preserved was the company’s fledgling color-printing and copying business. In 2000 large-scale color printing was still in its infancy, but Mulcahy placed a big bet that the ensuing decade would see huge growth. She was right. By 2007, 40 percent of Xerox’s total revenue would come from color printing, and Xerox products would capture the highest market share.

Early in her tenure as president/COO, Mulcahy met personally with key customers and the company’s top 100 leaders, sharing her passion and enthusiasm and convincing them to remain loyal during this difficult time. She told her sales force: “I will go anywhere, anytime, to save a Xerox customer.”

Her mission was nothing short of “restoring Xerox to a great company once again.” But the path to get there would be dogged with adversity. “There were many near-death moments when we weren’t sure the company could get through the crisis,” she admitted.

Not only was the company’s survival at stake but the struggle cut to the very core of Mulcahy’s identity. “One day I had just flown back from Japan,” she said. “I came back to the office and found it had been a dismal day. At around 8:30 p.m. on my way home, I pulled over to the side of the Merritt Parkway and said to myself, I don’t know where to go. I don’t want to go home. There’s just no place to go.”

In the midst of her despair, Mulcahy checked her voice mail and found a supportive message from one of her colleagues telling her how much everyone believed in her and the company. “That was all I needed to just drive home, and get up again the next morning,” she said.

Mulcahy’s leadership growth is even more remarkable when you consider her background. She had come through the ranks in sales, spent time in human resources, and had just become the general manager of a small, out-of-the-way business unit when she was tapped for the role of president/COO.

One of the most intriguing aspects of Mulcahy’s background is that she had very little financial training. She had never held a financial management job and felt clearly over her head as she navigated the hostile financial waters of disappointing earnings, stock market declines, and angry analysts.

Mulcahy’s untimely remark during the October 3, 2000, investor conference call is a good example of her financial inexperience. Her bold statement that Xerox’s business model was unsustainable may have been accurate, although there were undoubtedly more market-sensitive ways to communicate Xerox’s shaky financial status while still remaining authentic as a leader.

Fortunately, Mulcahy sought out capable mentors who helped her recover from that early misstep. In 2002, a year after being promoted to CEO, she personally renegotiated a $7 billion revolving line of credit, pulling together a consortium of 58 banks that needed to approve the deal. In the process she went toe to toe with Citigroup CEO Sandy Weill, successfully securing his commitment to personally reel in three holdout banks.

Mulcahy would summarize her experience as follows: “This was a job that would dramatically change my life, requiring every ounce of energy that I had. I never expected to be CEO, nor was I groomed for it.”

Bill Gates

In marked contrast to Anne Mulcahy, Bill Gates envisioned himself as a CEO at a very young age, and at every step in his career he took proactive measures to hone the skills he needed to actualize his vision.

I began working closely with Bill Gates in 1983, when I served as Microsoft’s liaison with IBM. At 28 I was just a year older than Bill. Microsoft, like the personal computer industry itself, was gaining traction. Still, with just $50 million in revenue and 250 employees, it was light years away from becoming the $74 billion behemoth it is today.

About two years into my tenure, Steve Ballmer, Bill Gates, and I were on an airplane flying back to Seattle from a successful meeting with IBM in Boca Raton. Bill and Steve were sitting together; I was a few rows forward with an empty seat next to me. In the middle of the flight, Bill came over to sit with me. After briefly talking about our development tools business, he asked me to become the general manager of the group.

I knew what a big deal that was to Bill. He was entrusting me with the company’s legacy. Microsoft got its start back in 1975 when Bill Gates and Paul Allen wrote the first BASIC Interpreter (one of the products in the development tools area) and licensed it to MITS on the first perso...