![]()

1

It’s Always the Culture

My job isn’t to make you happy. It’s to not give you an excuse.

—Anonymous help desk analyst

We’re starting every chapter with an interlude—a tale of either woe or success that is related to the chapter’s subject.

The interludes aren’t intended to be Aesop-style fables, perfectly crafted to make the chapter’s points, ending with “the moral of the story is . . .” They’re complementary to the subject matter, not duplicative of it.

We collected these interludes from seven sources we know and trust. While we’ve streamlined them, we’ve done our best to preserve their essence, and our sources have reviewed and endorsed them. In the Hollywood reality hierarchy, each one is “based on a true story”— definitely more accurate than “inspired by a true story” but fictionalized enough to not be unvarnished history.

Interlude: A Cultural Transformation

Back in the last century, the company where I worked was acquired. We were a well-established firm with a loyal customer base and a hard-driving national sales team. The acquiring company wanted to transform our successful product manufacturer/sales company into a company that would assist its customers in achieving their objectives through a long-term advisory relationship with their company representative.

No big deal, just move from a culture built on closing sales on as many of our products as you could while being careful not to give advice to the customer (it was a highly regulated industry) to one of intentionally consultative services with products available, as necessary—but a rigid, legal requirement to suggest products only when the customer had a proven need for them.

The acquiring company made a brilliant choice in hiring a savvy new leader to run the company. Rather than come in with guns blazing, giving directions on all the things that needed to change, he came in and spent time learning the current culture of the company. He then told us something that startled us. We were not going to be a rules-driven company. You couldn’t possibly write enough new rules/requirements to bring about the transformation required.

We were, instead, going to be a Vision/Mission/Values-based company. He put together cross-functional teams of the “heroes” in the company: the top salespeople, the top product development people, the long-tenured, well-respected sales managers, and so on. He then led them through a set of exercises to define the Vision/Mission/Values of the new company that we would become. They were concise, meaningful, and focused on helping our clients succeed. I remember those statements to this day.

Then, to top it off, he really shocked us. He asked us to operate at an “almost out of control” pace.

For those of us with conservative, risk-averse personality needs, this seemed like crazy talk. What if we made a mistake and it cost the company money or damaged the brand?

The new leader made it clear to the entire leadership team that any “mistakes” would be viewed through the filter of “Could you demonstrate that what you were doing was consistent with the Vision/Mission/Values and focused on serving customers?” If so, all would be forgiven. Learn from it (don’t repeat it) and move on.

It should be noted that there were multiple instances where this guidance was validated. As always, there were also instances where actions driven by a different agenda were taken. Those errors were not forgiven and people were held accountable.

We quickly transformed and created a new culture where staff internalized the company’s purpose and held each other accountable. In short order, our division became the crown jewel of the parent corporation. Those of us who participated in this transformation marvel at how much we were able to change as an organization and how much we learned. We have all taken that knowledge and experience with us to subsequent organizations and positions; however, whenever we reconnect through industry or social events, we invariably reflect on what an incredible, rewarding time it was to participate in transforming our organization.

In IT’s Precambrian* past, its practitioners held exalted status. They were the high priests of the glass house, and supplicants understood that IT operated at a different intellectual level than the rest of the company.

Then came its Pleistocene† fall from grace: IT professionals stopped being mythic gateways to the wonders of computing and became subservient providers to internal customers.

At first this seemed to be just another management fad, to be chuckled at but not taken too seriously.

But what started as a ridiculed change in vocabulary became, over the span of decades, an ingrained part of the IT and business management cultures . . . and subcultures . . . in most of the world here in commerce’s Holocene epoch.*

As is the case with most business change, culture is less of a barrier or enabler than it is the lead story.

And in spite of what you might think, culture is not an intangible I’ll-know-it-when-I-see-it “warm fuzzy.” It’s an aspect of the organization that’s just as susceptible to engineering as its processes and technologies.

Susceptible, but, because those pesky human beings are involved at every step, engineering culture calls for considerably more patience.

What Is This “Culture” Thing of Which You Speak?

Business leaders talk about culture all the time. What do they mean when they use the word? Chances are, they aren’t all that sure themselves. So let’s get precise.

Culture is how we do things around here. It’s how we think about things. It’s our attitudes, shared knowledge and values, expectations held in common, and specialized vocabularies. It’s the organization’s unofficial policy manual—a collection of unwritten rules that are rigidly enforced by the inexorable power of peer pressure.

It is, in operational terms, the learned behavior employees exhibit in response to their environment, their environment consisting largely of the behavior of the employees who surround them.

That is, it’s the learned behavior employees exhibit in response to the learned behavior employees exhibit in response to the learned behavior . . .

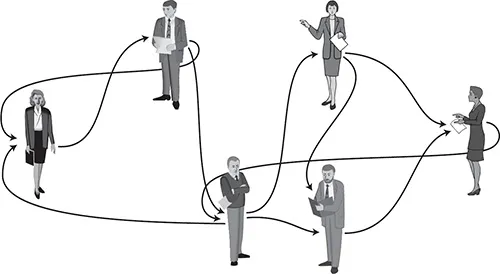

FIGURE 2 Culture is the learned behavior people exhibit in response to the learned behavior people exhibit in response to the learned behavior people exhibit . . .

It’s a self-reinforcing feedback loop, which makes it highly stable and difficult to change—frustrating when you want change to happen, but welcome when it lines up with what you’re trying to accomplish (see figure 2).

How to Describe Culture

Before we can talk about how to change culture, we first have to know how to describe it. We need a way to describe the culture we have, the culture we want, and the difference between the two.

Go back to the operational definition—the learned behavior employees exhibit in response to their environment. Environment in this context consists of situations. Behavior is how employees respond to situations.

The way to describe culture is as a set of situation/response statements.

But there’s a caveat to this: it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking you’re describing culture when all you’re doing is writing procedures.

Let’s start by trying to describe your help desk’s culture:

Situation: The automated call distributor (the system call centers use to queue up calls) routes a caller to a help desk analyst.

Response: The help desk analyst (1) reads the greeting script, (2) records the caller’s name and employee ID, (3) looks for open tickets associated with the employee ID, (4) and so on.

This is entirely unhelpful. It describes procedure, not culture. Here’s an entry that helps describe help desk culture:

Situation: An employee describes a problem whose solution is, to the help desk analyst, simple and obvious.

Response: The analyst rolls his eyes and, while patiently explaining the solution to the caller, makes a mental note to share the call with his lunch buddies as another dumb-user story.

Descriptions of culture are behavioral, but they reflect attitude.

The Culture We Have; the Culture We Want

When a company describes its major projects in terms of IT delivery, a number of mental habits are commonly in play. Here are a few samples, contrasted with the culture in play in companies that describe them in terms of their intended business changes. Your mileage may vary. If it does, we encourage you to develop equivalents that fit your actual situation:

• Where there are IT projects, business executives view project proposals with suspicion. They see their job as screening out bad ideas, which is why they insist that the CIO provide a hard-dollar return on investment, typically calculated as the number of warm bodies to be laid off multiplied by their annual compensation plus benefits.

Where there are no IT projects, business executives view project proposals as opportunities to improve how their company conducts its business. They see their job as helping good ideas succeed. Because of this they insist that all project proposals be described in terms of business change, described that way by a business sponsor who is enthusiastic about the possibilities and supported by an IT SME who attests to the project’s technical feasibility.

• With IT projects, business managers are busy people. They look for parts of their operation that should be automated, figure it’s up to IT to figure out how to provide the automation, but don’t have much time to spend with IT—they want IT to just tell them when it’s done.

With no IT projects, business managers are just as busy. But they make time to talk with IT’s internal business consultants, asking them for ideas on how to make their areas of responsibility more effective. And, they rearrange their calendars so they can stay involved throughout the process of making the ideas real.

• In IT project-land, a business analyst wouldn’t think of visiting, say, the company’s raw materials warehouse when designing a warehouse management system. A business analyst’s responsibilities begin and end with interviews with SMEs to document requirements.*

In the land of truth and righteousness—as you’ll read in the next chapter—there are no business analysts. Instead, IT has a staff of internal business consultants. These folks were born with the curiosity gene, which drives them to want to understand in depth the parts of the business they’re responsible for, so they can envision a variety of ways to improve things.

• If business change is a battle to be won, project managers are the sergeants who win it. That’s when there are no IT projects. When there are, project managers are the sergeants who make sure IT delivers its defined work products, and then insist there’s nothing left to be done.

• And with IT projects, IT developers, as described in the introduction, see their job as translating written requirements and specifications into a bug-free software product. Understanding the business isn’t part of their job description; helping change it is Someone Else’s Problem entirely.

When projects are defined in terms of successful, intentional business change, in contrast, IT developers spend a lot of time talking with business users because they see no way to succeed without collaborating with their colleagues who work in the affected part of the company.

In even more enlightened companies they sometimes become business users for a while so they can envision firsthand what software can do to improve the situation.

• And finally, with IT projects, the projects needed to keep the IT infrastructure current and in good shape are IT’s problem, and that includes funding them, on the grounds that if the project doesn’t directly benefit my part of the business, I don’t know why I should have to pay for it.

After the no-IT-projects culture change, all business leaders will recognize that an obsolete or poorly engineered IT infrastructure is a serious business risk, whether or not it’s able to run everyone’s applications right now.

You might have noticed that the “with IT projects” examples— those describing the culture we’re coming from—all sound pretty bad. That’s premeditated.

For the most part, cultural traits are neither good nor bad. They are, however, either consistent with and supportive of the business change you’re trying to achieve or run counter to it.

In case the point isn’t clear . . . in case you think cultural traits that run counter to what you’re trying to accomplish are bad . . . consider the case of World War II. In World War II we considered those resisting change to be the good guys, which is why we called them “The Resistance.” Our words for those promoting change were considerably less flattering.

That’s the point: while in absolute terms cultural traits are neutral, you’re free to choose the language you use when describing both the “from” culture and th...