![]() PART I

PART I

A New Way of Thinking and Acting: Developing Cognitive Ambidexterity![]()

CHAPTER 1

Cognitive Ambidexterity: The Underlying Mental Model of the Entrepreneurial Leader

Heidi Neck

IN 2003 JIM POSS WAS WALKING DOWN A BOSTON STREET WHEN HE noticed a trash vehicle in action. The truck was idling at a pickup point, blocking traffic, smoke pouring out of its exhaust, and litter was still prevalent on the street. There has to be a better way, he thought to himself. In investigating the problem, Poss learned that garbage trucks consume more than 1 billion gallons of fuel in the United States alone. The vehicles average only 2.8 miles per gallon, and they are among the most expensive vehicles to operate (BigBelly Solar 2010). In the early 2000s, municipalities and waste collection services were considering more-fuel-efficient vehicles and better collection routes to reduce their overall costs and environmental footprint. Poss was not convinced that this was the right approach.

Through interactions with diverse stakeholders, he turned the problem upside down. He considered that the answer might not be about developing a more efficient collection process but about reducing the need for frequent trash collection. As he considered this solution, he discovered multiple benefits: if trash receptacles held more trash, they would not need to be emptied so often; if trash did not need to be collected so often, collection costs and associated pollution would be reduced; and if receptacles did not overflow, there would be less litter on the streets. There were many advantages to this approach.

By applying the solar technology he used at work, Poss envisioned how a new machine might better manage trash. His initial concept of a solar-powered trash compactor was dismissed in favor of other ideas for environmentally friendly inventions, including a machine that would generate electricity from the movement of the ocean. Nonetheless the problem and the potential solutions continued to occupy his mind. Poss said, “I took pictures of trash cans on my honeymoon” (Simpson 2007).

He began to involve others, choosing a team based on who he knew might be interested within his social network. “We are motivated in part because we care about the environment and in part because we know this can be financially successful” (Xing 2007). Poss and his assembled team experimented with a variety of options and finally returned to the solar-powered trash receptacle—the BigBelly—an innovation that provides clear solutions to the problems he noted on the city street that day. The current version can hold up to five times more trash than traditional receptacles. As a result, it dramatically decreases the frequency of trash pickup and cuts fuel use and trash truck emissions by up to 80 percent.

Entrepreneurial leaders such as Jim Poss need the skills and the knowledge to define the world rather than be defined by it. To achieve this, entrepreneurial leaders must identify, assess, and shape opportunities in a variety of contexts—ranging from the predictable to the unknowable. They use creative and innovative approaches to create value for stakeholders and society. They create opportunities using a method of observing, acting, reflecting, and learning that is a constant and ongoing process. This is the method Poss used when observing a waste collection problem, pondering new technology-based solutions, reflecting on the possibilities, and creating the BigBelly solution.

In this chapter we introduce the way of thinking and acting that underlies entrepreneurial leadership: cognitive ambidexterity. Cognitive ambidexterity presumes two different approaches to thought and action: prediction logic and creation logic. To be an effective entrepreneurial leader, one must be skilled in both prediction and creation logics and able to cycle between them. It was through the use of both prediction and creation logics that Poss was able to create economic and environmental value; he literally turned garbage into an opportunity.

This chapter explains cognitive ambidexterity in more detail and provides examples of how to develop entrepreneurial leaders who engage cognitive ambidexterity. To do this, however, management education must move beyond teaching entrepreneurial leaders what to think to teaching them how to think.

Cognitive Ambidexterity: Linking

Prediction and Creation Approaches

Entrepreneurial leadership requires cognitive ambidexterity—a way of thinking and acting that is characterized by switching flexibly back and forth between prediction and creation approaches. The prediction approach, which is based on analysis using existing information, works best under conditions of certainty and low levels of perceived uncertainty. Creation, on the other hand, involves taking action to generate data that did not exist previously or that are inaccessible. It is most effective in environments characterized by extreme uncertainty or even unknowability.

In some instances prediction and creation logics are portrayed as incompatible methods of thought and action. In theory and in practice, this distinction is artificial. Through conscious effort, one way of thinking can be used to inform and progress the other way of thinking, making the approaches complementary. Moreover, by engaging prediction and creation approaches, entrepreneurial leaders are able to create greater value than if they had tried only one of these approaches.

Consider the example of Yvon Chouinard, who founded the outdoor apparel company Patagonia in 1974. When asked how he knows if he’s making the right move, he responded, “If you study something to death, if you wait for the customer to tell you what he wants, you’re going to be too late, especially for an entrepreneurial company. That comes from Henry Ford: Customers didn’t want a Model T, they wanted a faster horse” (Wang 2010, 23). Chouinard takes action first (the creation approach) and uses data from his actions and experiments to make decisions (the prediction approach). His cognitive ambidexterity is producing impressive results. Patagonia is still a private company, 100 percent owned by Chouinard, with approximately 1,300 employees and $315 million in sales for 2009. In addition, Patagonia continues to receive numerous awards for its emphasis on social and environmental responsibility and sustainability (Wang 2010).

Framing Cognitive Ambidexterity

for Entrepreneurial Leaders

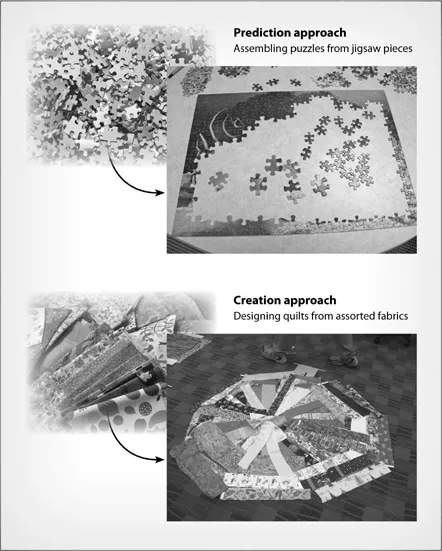

To understand the abstract concept of cognitive ambidexterity, we developed an exercise that enables entrepreneurial leaders to experience the difference between the prediction and creation ways of thinking. The exercise we describe is based on Sarasvathy’s (2008) seminal work on effectuation, where the contrasting metaphors of a quilt and a jigsaw puzzle expose the differences between effectual and causal thinking, which are akin to creation and prediction logics (see exhibit 1.1).

This exercise can be used at the beginning of any course that discusses entrepreneurial leadership. At the start of the course, students are least comfortable with one another, the professor, and the course content. In this way course participants simulate the experience of being in an unknowable world. The exercise begins as the professor asks students to count off into groups of six. The professor tells students that this is a time-limited competition. Groups are instructed to go to their assigned table, which has the directions.

Exhibit 1.1 Exercise to introduce cognitive ambidexterity

At each table participants read the instructions, which indicate that their task is to complete a 300-piece jigsaw puzzle as quickly as possible. While the initial setup may be a little chaotic, order quickly appears at each table, as most students have experience doing jigsaw puzzles. Group members use their experience as they begin to separate edges from center pieces, search for corners, and use the picture on the box to begin assembling the puzzle.

After five to 10 minutes, the professor announces that one volunteer is needed from each group. The volunteers leave the puzzle area and are brought to a large, empty room. In one corner of the room are hundreds of pieces of fabric of different colors, textures, and sizes. The group of volunteers are again confused and concerned. The instructor tells them that each student will now become a quilt leader responsible for designing a quilt that will be judged. Quilt leaders are told that they don’t need to sew; they can simply place fabric on the ground and start designing the quilt. They begin the process by choosing six pieces of fabric, selecting a space in the room to create the quilt, and laying their pieces down. The quilt leaders are also told that over the next 45 minutes, other volunteers will be brought into the room and will be invited to join in designing quilts.

The quilt leaders get to work, and in five minutes six more volunteers join the quilt-making room. These volunteers are told to select six pieces of fabric and join any team they want. Every five minutes a new group of volunteers leave the puzzle-making area and enter the quilt-making room. As more people join the effort, some quilts grow larger or become more creative. Soon the entire class moves from putting together puzzles to designing quilts. Though participants don’t yet realize it, they have just experienced the prediction and creation logics of cognitive ambidexterity.

The Jigsaw Puzzle as Prediction Logic

Assembling a jigsaw puzzle is analogous to prediction logic within cognitive ambidexterity. The puzzle box itself offers a number of known variables, including the number of pieces inside and a picture of the solved puzzle, both of which can be used to reduce uncertainty around the level of difficulty and potential time to completion. The process begins by establishing the goal: complete the puzzle. The second step is to acquire resources to achieve that goal: open the box and get the puzzle pieces. The third step is to analyze everyone’s experience with puzzle building and to design a process for completing the puzzle. This might involve separating pieces by color, doing the edges first, and so on. The fourth step involves measuring progress and making adjustments by reviewing the box cover and revising the plan. Finally, the project is complete when all the pieces are connected to match the picture on the box. Participants start with a clear goal and follow a linear process to completion.

Prediction logic, which is vividly illustrated by the experience of assembling a jigsaw puzzle, is the established analytical approach taught by most management educators. The concepts and the teaching methods that underlie this approach provide students with the tools, frameworks, and processes for analyzing the causes and predicting the effects of a given event or action. Through this approach management students learn how to predict the outcome of actions using observation, experience, analysis, and reasoning. They learn that through rigorous analysis of the causes and the effects of a situation, they can make decisions that yield the intended results.

The six principles that guide the use of a prediction approach are shown in the following sidebar. Like putting together a jigsaw puzzle, a prediction approach is applicable in organizational situations in which goals are predetermined, issues are clear, and data are reliable and available. In these circumstances entrepreneurial leaders focus on assessing the situation, defining the problems and the opportunities, diagnosing the problem, evaluating alternative actions using established frameworks and tools, and identifying the best solution or plan to reach established goals. This sequential process of assess, define, diagnose, design, and act assumes that we can predict the future based on past experiences.

Principles of a Prediction Approach

to Thought and Action

1. Goals are predetermined and achievable given known information.

2. Enough information is known for rigorous analysis and testing.

3. Tools and frameworks are available to guide decision-making.

4. Optimal solutions are identifiable within a given set of constraints.

5. Through analysis, risk can be minimized or mitigated to achieve optimal returns.

6. Outside organizations are seen as competitors and barriers to future growth.

Adapted from Dew et al. 2008; Greenberg et al. 2009; and Sarasvathy 2008.

In management education prediction logic has been the dominant paradigm for teaching everything from accounting to organizational behavior to entrepreneurship. To develop their cognitive ambidexterity, entrepreneurial leaders will still need to be taught the prediction approach. They need to learn established tools and frameworks for following a rigorous, analytical decision-making process.

Yet the ambiguity of today’s business environment means that a prediction approach to leadership is not enough. In complex situations where cause-and-effect relationships are unknown or uncertain and where information is ambiguous, a prediction approach must be complemented by the creation approach based in action, discovery, and shaping opportunities. Entrepreneurial leaders use the creation approach to learn about a situation by acting and then observing and analyzing the outcomes of their actions.

The Quilt as Creation Logic

The creation approach illustrated by this experiential exercise is analogous to a form of quilt-making called crazy quilting. Crazy quilting is one of the oldest forms of American patchwork quilting and is defined by combining irregular patches of fabric with little or no regard to pattern or design. This form of quilt-making became popular among Victorian women in the late 1800s. The design, shape, and color of the quilt depended not only on the knowledge and the experience of the quilters but also on the amount and the type of fabric and the creativity they brought to the project.

The quilt-making portion of the exercise highlights the creation component of cognitive ambidexterity. Participants enter the quilt-making room with little information and few resources (six pieces of fabric). They employ a means-focused process in which they begin designing the quilt based on the materials they have. This is very different from creating a quilt design and then going to find the materials that fit it (a prediction-oriented process).

As other participants enter the room, they self-select to join a quilt leader. How they choose a quilt-making team varies. Some participants are attracted by a quilt leader’s design and feel they have something to offer. For instance, some may be drawn to a quilt that is unconventional. Other participants connect to those who fit with their knowledge of what a quilt is supposed to be. Still others see that some teams do not have many people, so they join out of perceived need. Regardless of the reason why, each volunteer brings additional resources (fabric), and the quilt design continues to emerge. Sometimes new fabric brought to the team may force the team to go in a different direction. For example, a team may have an emerging design based on hues of blue, and then someone joins the team with red, orange, and green plaid pieces. Should the team accept the resources and go with a different design? The creation approach would argue affirmatively because with each additional set of resources the pool of possibilities expands.

Entrepreneurial leaders use creation logic when the future is highly uncertain and unpredictable and past information is not predictive of future activity. Creation logic is an action-oriented approach based on the notion that new inputs (actions, information, and resources)...