Chapter 1

“The Olmsted City”

Heritage Landscapes and Civic Identity in Twentieth-Century Buffalo

Stewart Weaver

Approaching downtown Buffalo from the east on Interstate 190—the Niagara Section of the New York State Thruway—one hurtles thoughtlessly through the sprawling “geography of nowhere.”1 Strip malls, office parks, housing tracts, cell towers, high tension lines—all the dreary detritus of American exurbia slides past the windows at dizzying speed, and absent any obviously identifying features one might think oneself anywhere in that vast intermediate territory where the East gradually elides with the Midwest. Unless, that is, when crossing the city line one happens to catch a passing glimpse of a weathered, weed-choked, soot-begrimed sign that says “Welcome to Buffalo: Home of the Olmsted Parks System.” It stands stranded in the grassy verge of the South Ogden Street entrance ramp—as incongruous a tribute to the great apostle of the American pastoral as can possibly be imagined. And it hardly lessens the irony to know, as a few passersby might, that just ten miles ahead, Interstate 190 will completely overwhelm Front Park, an Olmsted-designed esplanade that once peacefully overlooked Lake Erie; or that twelve miles ahead, it will merge with the Scajaquada Expressway, a crosstown “arterial” that since the 1960s has brutally bisected Delaware Park, once Olmsted’s pride and joy; or that fourteen miles ahead the Scajaquada in turn will merge with the Kensington Expressway, a six-lane asphalt monstrosity that in 1958 obliterated one of the most beautiful and distinctive streets in America, namely, Frederick Law Olmsted’s Humboldt Parkway. Welcome to Buffalo indeed, one might think, former home of the Olmsted Parks System.

But that would be unfair. For all the depredations and degradations of the years—and the expressways are only the most obvious of these—much of Olmsted’s work in Buffalo survives, both physically and psychologically, and even in its mangled form it remains one of the most original and distinctive park ensembles in the United States.2 Moreover, it is slowly returning from the brink of extinction and beginning to resume something like the prominent place in the social and topographical life of the city for which it was first designed. The same could be said, of course, of Central Park or Prospect Park or Franklin Park or any number of other Olmsted-designed landscapes across the country. They have all come back from the brink since the 1970s, when the word “park” scarcely applied to the dilapidated and dangerous places they had become. But Buffalo’s case is nevertheless distinctive in two crucial respects.

First, no other city of comparable size fell so far or so fast in the postwar period. Buffalo lost half its people and almost all its manufacturing industry between 1950 and 2000. Even for the rust belt, such decline was dizzying, and it left Buffalo in especially dire need of a reason for being. And second, no other city of any size has so comprehensive a collection of Olmsted artifacts—not just parks, but parkways, gardens, playgrounds, parade grounds, hospital grounds, civic squares, carriage drives, promenades, and residential neighborhoods. New York has its Central Park, Boston its Emerald Necklace, Montreal its Mont Royal, but Buffalo, Francis Kowsky argues, was the client for whom Olmsted exercised “the fullest measure of his genius,” and in that circumstance (insofar as it is true) lay a unique claim on his legacy and the basis of a new urban identity for a postindustrial age.3 The Queen City; the Nickel City; the City of Light; the City of Good Neighbors—Buffalo has had many a moniker over the years. But it was only in 2003 that then-mayor Anthony Masiello officially proclaimed it “the Olmsted City” in a somewhat backhanded tribute to a park system that his predecessors had very nearly destroyed. No other American mayor has done this; no other urban territory asserts so direct and forceful a claim on the Olmsted heritage; nowhere else than in Buffalo, that is to say, do we see so clearly how a once-prized cultural landscape came first to be forgotten and abused and then suddenly remembered, reclaimed, and (partially) restored to its place at the center of American civic consciousness.

Figure 1.1 “Welcome to Buffalo”: the sign that has greeted northbound motorists on the Niagara Thruway at the Buffalo city line since June 2000.

Photo credit: Stewart Weaver.

“The Best Planned City”

Frederick Law Olmsted’s brief but consequential acquaintance with “the Queen City of the Lakes” began on August 16, 1868, when, en route to Chicago, he stopped off in Buffalo at the invitation of William Dorsheimer, the US district attorney for northern New York and the leading figure of a group of civic-minded citizens seeking to lend a sylvan aspect to their fast-growing but otherwise unremarkable hometown. Already renowned as the co-architect (along with his partner Calvert Vaux) of New York’s Central Park, Olmsted was at that time busily engaged in the making of Prospect Park, Brooklyn, and the residential subdivision of Riverside, Illinois, but what he saw in the course of a one-day tour of Buffalo intrigued him, and a week later he interrupted his return trip to New York for a closer look. Thus far in his young career as a landscape architect, he had been involved in the design and construction of individual parks, but in Buffalo he for the first time perceived a different possibility: not a single central park of the sort that Dorsheimer and his fellow worthies had in mind—that is, something to rival the great new parks of New York and Brooklyn—but a park system, a comprehensive ensemble of interconnected parks and parkways that would extend its salubrious influence throughout the far-flung territory of the city. Despite its obvious wealth and energy, and despite the elegance of Joseph Ellicott’s radial street design, Buffalo and its “immediate environs” struck Olmsted as “not generally at all attractive.” The relation of the town to its canals, railroads, and rivers was such “as to make an escape from it in several directions, to anything like rural quiet, difficult and disagreeable if not impossible,” he wrote, especially during that “considerable part of the year” when the “portion of the environs” that was “otherwise least repellent to rural exercise” was swept by “harsh, damp winds.” In light of all this and more, any landscape scheme for Buffalo had to be “comprehensively conceived.” A single large park, however desirable and necessary, “should not be the sole object in view,” Olmsted argued, “but should be regarded simply as the more important member of a general, largely provident, forehanded comprehensive arrangement for securing refreshment, recreation and health to the people.”4

Under the authority of the newly established Buffalo Parks Commission (1869), the main elements of the Buffalo park system went in more or less according to Olmsted and Vaux’s original conception between 1871 and 1876. Foremost among these was the 350-acre expanse that Olmsted called simply “the Park.” Here among the gently rolling meadows and forest stands north of Forest Lawn Cemetery, Olmsted indulged more fully than almost anywhere else the pastoral impulse for which he is most known. The heart of the Park was a greensward meadow twice the size of the famous Long Meadow in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Here was room enough indeed for that “sense of enlarged freedom” that was, Olmsted believed, the very essence of the park experience. Southwest of the meadow, where Scajaquada Creek flowed gently out of Forest Lawn Cemetery, Olmsted placed a picturesque “water park” around a forty-six-acre artificial lake. Together with the happily adjacent gothic cemetery, the pastoral meadow (complete with sheep and deer paddock) and the picturesque “water park” made for a remarkable landscape ensemble and the most notable addition thus far to Olmsted’s oeuvre outside of New York and Brooklyn.5

And still “the Park” was only the offset centerpiece of a remarkable landscape triptych that also featured “the Front,” a thirty-five-acre esplanade and playground overlooking Lake Erie and the Niagara River, and “the Parade,” a fifty-six-acre drill and picnic ground on the city’s East Side. Both of these smaller, satellite spaces Olmsted envisioned as active recreational complements to the larger contemplative sanctuary of the Park, and in placing them closer to the heart of downtown, he purposefully meant to integrate them more fully into the swirling life of the city. But they were still places apart, still places of quasi-rural refuge from the noisome influences of the commercial and industrial districts, and as if to emphasize their significance to the overall scheme of things, Olmsted and Vaux designed a series of wide, shaded, grassy avenues to join them to the Park, to downtown, and to each other. These “park ways,” as the partners called them, were in some respects the most distinctive and original feature of the entire Buffalo system. Two hundred feet wide and planted with rows of overarching elms, they extended the parklike atmosphere throughout the city and served themselves as parks, in fact, arterial parks “suitable for a short stroll,” Olmsted wrote, “for a playground for children, and an airing ground for invalids, and a route of access to the large common park of the whole city of such a character that most of the steps on the way to it would be taken in the midst of a scene of sylvan beauty, and with the sounds and sites of the ordinary town business, if not wholly shut out, removed to some distance and placed in obscurity.”6

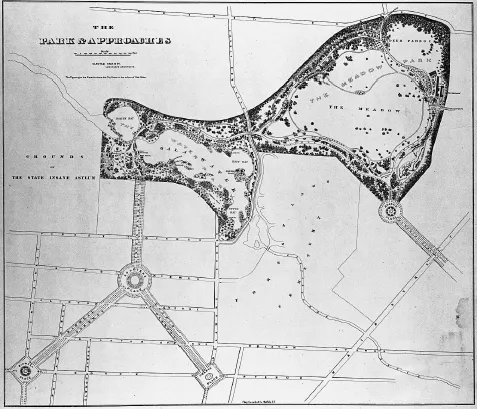

Figure 1.2 “The Park & Approaches.” Olmsted, Vaux, and Company’s plan for the Park (now Delaware Park) and the four parkway approaches to it, circa 1870.

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

The Park, the Front, the Parade, and their interconnecting parkways were the four original elements of Buffalo’s Olmsted-designed park system. There were more elements to come. But in the meantime, even as the parks were under construction, Olmsted was at work on two other projects that adjoined “the Park” and together with Forest Lawn Cemetery made for a unique green space aggregation. First, in 1871, he and Vaux accepted a commission to design the grounds of what was then known as the Buffalo State Hospital for the Insane. Here, on land immediately to the west of his “Gala Water,” and in friendly collaboration with the young architect H. H. Richardson, Olmsted made fully explicit the psychic purpose that lay behind his entire theory of landscape design. The whole point of a park, as he understood it, was to provide mental relief from the strains and anxieties of urban life. A park was above all recuperative; it was restorative. If well designed it allowed for the “unbending,” as Olmsted put it, of overtired and overtaxed faculties. As did, ideally, a well-designed residential community of the sort that the private investors behind the Parkside Land Improvement Company had in mind when they asked Olmsted to design a “detached suburb” on land wrapping around the Park to the north.

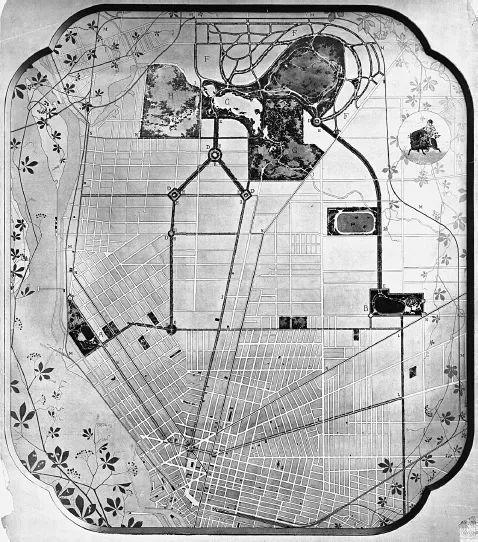

Figure 1.3 Olmsted’s plan of Buffalo highlighting the new park and parkway system for display at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia.

Courtesy of the National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Neither the asylum grounds nor “Parkside” ...