![]()

Let’s start with the question, why the discussion on the measurement of government should be important at all. Following fundamental changes in the field of mainstream economic theory in the first half of the twentieth century, the role of government in economic affairs has become one of the predominant concerns of economists. So, economic researchers have put a great deal of effort into finding out an optimal size or scope of government, which draws on mutual causal links between relevant macroeconomic aggregates like government expenditures and economic growth, or government indebtedness and inflation rates. Undoubtedly, statistics, that is the quantitative measurement of abstract economic concepts, is the sine qua non of empirical research.

To bring economic concepts into existence by way of appropriate quantifications is left almost exclusively to statisticians. Admittedly, after many decades of rapid development in economics and statistics, we have arrived at the point where economists rely on statistical quantifications, but are at the same time little aware of how these figures have been compiled.1 On the other hand, most statisticians have little idea of all the purposes for which the result of their work is used. This situation is apparently further enhanced by a precipitous development on both sides, i.e. a growing complexity of the methodology of macroeconomic data and a broadening of its use in economic policy.

In the case of macroeconomic aggregates, we are not talking about monetary categories easily observable. As Morgenstern (1963) reiterates, statistical observations are based on the constructed, deliberately designed and invented theory. The compilation carried out by professional statisticians is a lengthy and highly complicated process. Lack of information and methodological complexity creates an environment in which an occurrence of measurement errors is inevitable. In his famous book, Morgenstern (1963) further enumerates several sources of error negatively affecting the accuracy of economic calculations. For the sake of our argument, chiefly the lack of clear definitions of the government sector, one of the sources of errors stated by Morgenstern, is of vital importance. Morgenstern rightly notes that weak and unsteady definitions cannot provide a stable ground for reliable quantifications.2

1.1 Economic theory

Macroeconomic textbooks abound with terms like government, fiscal expansion, fiscal restriction, government debt, but it is only exceptionally accompanied by any thorough reference to the substance of these terms. So, what is meant under the term “government”? Here we are referring to an entity whose actions generate effects for the economy through, in the words of modern macroeconomics, “expansionary or restrictive fiscal policy”.

The role of government is illustrated by the total of government consumption expenditures, the famous “G”. Through management of its consumption expenditures, government is supposed, especially according to Keynesian theory, to stabilize business cycles. As Keynesian theory holds, G is supposed to be a stabilizing part of GDP whereas this deliberate government policy is necessitated by presumed instability of investment expenditures (“I”). As the theory goes, if aggregate demand falls short of that level required to maintain full employment, government shall step in and counterbalance falling demand even at the cost of deficit. On the contrary, if aggregate demand threatens to cause price inflation by way of excessive employment, i.e. above the full level target, government shall drain income to cool down an overheating economy, i.e. to create a budget surplus.

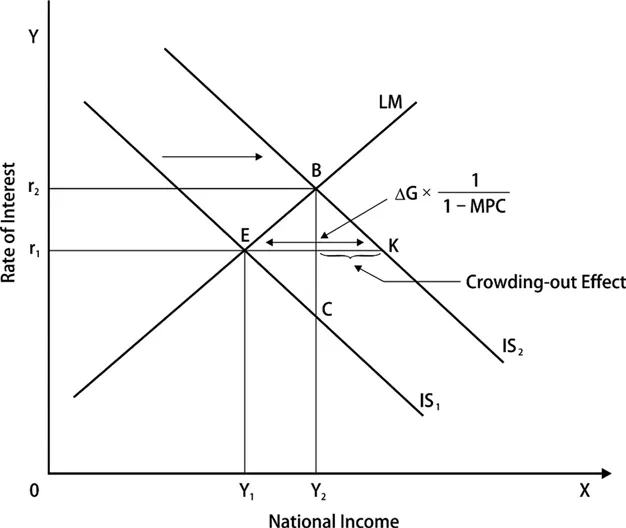

The aggregate “G” thus stands in the centre of those considerations. We can illustrate this by using the famous neo-Keynesian Mundell–Fleming model which deals with the effects and efficiency of fiscal (and monetary) expansion under different circumstances like capital (im)mobility or fixed/flexible currency regimes. Because the model is based on the basic Keynesian model of output and income, it counts with government expenditures, which are treated as a part of total output (or income). As this theory holds, the fiscal expansion, i.e. growth in “G”, is effective in the short term if some specific circumstances are met, for example, if exchange rate is flexible and capital is perfectly mobile. A growth in planned expenditures (G) gives rise to a shift in output; because of a government action and multiplication of newly injected expenditures, the economy will find its new equilibrium at a higher level of economic activity and income. This is illustrated by Figure 1.1.

To make these concepts applicable, workable and testable, even this model needs to be loaded with data. There are, here, at least two methodological issues that go mostly unnoticed by economists or, to rephrase that, most economists are unconcerned with them. First, as Auerbach, Leibfritz and Kotlikoff (1999) point out, Keynesian economists take a cash flow measure of policy. That is to say, the fiscal expansion or restriction is achieved through cash expenditures or accumulation of cash in the hands of government. This “cash-approach” is deeply rooted in the key Keynesian assumption on the short-sightedness of people in economic affairs. Auerbach, Leibfritz and Kotlikoff further draw attention to the fact that the financial consequences of government behaviour are spread over time affecting also welfare of future generations. Even if Kotlikoff’s central point is different from ours,3 this brings us to the important issue of an accounting principle on which fiscal figures should be based.

For the sake of the quantifications of macroaggregates, relying on the cash approach would tell use little about actual economic development. Economic activity might be carried out no matter how resulting transactions are settled. Payments of invoices might be postponed, the existence of long-term contracts or the settlement might be executed through other means like barter exchanges. The national accounts methodology thus applies the accrual principle recognizing creation of values irrespective of the way of settlement. This supposedly makes the results more realistic. Nevertheless, this might pose difficulties for judging whether an economic boom is sustainable, or predominantly debt-driven, or accompanied by a growing insolvency.4

When assessing the financial situation of government, the application of accrual principle is undoubtedly preferable.5 It is not exceptional that government enters into long-term contracts, such as leasing contracts, guarantees, PPPs or restitutions schemes, within which framework cash payments are commonly postponed to the future. Government thus makes no payment at the time of making a deal; nevertheless, an obligation to pay at some point in the future arises. Were figures based on the cash basis, all these actions would be kept from observations. Based on cash flows, macroaggregates would not only provide us with an incomplete idea of government actions, but it would create a wide space for manipulations, for example, by delaying cash disbursements or one-off revenue from selling long-term licences.

Another issue that deserves to be closely addressed is which institutions can actually set a fiscal expansion in motion? Which institutions can transmit impacts of government actions down into the economy? And, is there necessarily a clear link between fiscal expansion and changes in “G”? Definitely not. It is not exceptional that government instructs a public institution under its own control, but legally separated from the state, to enlarge their expenditure to help improve politically sensitive economic indicators like growth or unemployment rate.

This way of government operation might be exemplified by a number of institutions. It has become common for government, in their attempt to promote growth, to establish a specific agent providing loans or guarantees. This is commonly the case of public banks required by government to extend loans provision to infrastructure managers in order to increase the volume of public procurements, especially in times of economic distress. Financially, their activities have only limited impact on the state budget, aside from in very exceptional cases such when there is a need for recapitalizing. As these institutions are legally entitled to issue their own bonds or to take a loan, benefiting from explicit or implicit government guarantee, fiscal expansion can be easily carried out without any recognition in the accounts of the state. It implies that neither “G” nor other fiscal indicators are impacted by an ongoing fiscal expansion.

Another example is the case of public transport companies. Government-owned transport companies might be made by central or local government institutions to purchase new vehicles from private manufactures in order to promote employment and production in a specific region. If public transport companies stand outside the general government sector, fiscal indicators, including “G”, go unaffected by (not only) this growth-promoting government measure. To conclude for now, the point here is not to enumerate all the possible ways which might be exploited by government to tune the performance of an economy – the full list is probably beyond this author’s imagination – but the point is that the delimitation of the government sector matters even for the practice of theoretical economics.

Statisticians have thus tried quite hard to take the expansion of government power into account so that the actual substance of “G”, today, goes far beyond the state budget. A soaring government sector, however, does not affect only the structure of GDP, as private consumption is lowered in favour of government consumption expenditures, but also the value of GDP. Before going into detail, let’s look first at the well-known definition of GDP or aggregate demand:

GDP = C + I + G + NX

GDP sums up expenditures on private consumption (C), investment and net exports (NX) which is obtained as a difference between exports and imports. The explanatory power of GDP might be questioned for many reasons ranging from exclusive attention being paid to the final products up to its holistic nature telling little about changes in the structure of economy.6 Focusing on the issue of government, we should stress that government actions are directly embodied not only by the component “G”, but also partly by “I” as this covers also government investments. This fact thus implies that fiscal expansion is not exclusively a matter of changes in “G”; we should rather count up “G” and a part of “I” to arrive at a true transaction of government with so-called final products.

How is the value of GDP itself affected by the definition of the government? To figure it out, we can ask a simple question: what happens if a public institution is newly moved into the government sector? In case of investment, the situation is quite clear; the total of investment in the economy remains unchanged, a part of investment is only switched from one sector to the general government. In case of “G”, an impact is much less predictable. That is because the overwhelming majority of government products are valued at costs as the second-best approach to the valuation of products delivered at non-market terms. An impact on GDP thus depends on the share of revenues on production costs before a unit were moved to the general government.

Let’s make a few more remarks on the valuation problem. All products covered by GDP shall be preferably valued at market prices. However, a certain part of products counted in GDP is not marketed at all, as is the case of government’s provision of national defence, justice or public administration. Besides, there are products delivered by government institutions on the non-market basis where market alternatives exist, such as provision of healthcare, education or transport. For the former, there is no other option for statisticians than to apply the valuation at costs incurred in their provision. This, of course, calls into question the interpretation of GDP as the gross values added of all resident producers at market prices.

For the latter, the valuation at costs is not the only option. Apart from the cost-approach, statisticians can look at the market with the products akin to that of government, i.e. to take prices of market products satisfying similar needs of consumers. Even if this approach is methodologically acceptable and technically doable, room for dispute remains because the quality and costliness of government products might be incomparable to their market “equivalents”.

Statisticians thus bypass the non-existence of market alternatives or incomparability of products delivered by government and market by application of the “cost-method” mentioned above. The vast majority of government products is then valued by putting selected costs incurred in their production, mainly intermediate consumption, compensation of employees, and depreciation of fixed assets. The application of the cost-method leads to a quite paradoxical situation in which the more government spends, at the higher nominal level of GDP we arrive.

To make the long story short, a public producer transferred to the general government sector normally gives rise to an increase in GDP. The reason is that prices charged by public producers commonly do not cover the total production costs. Then, the switch from valuation of output at revenues from final users, as is the case of non-government units, to the cost-method used for the valuation of output of government institutions pushes up the nominal GDP.

Consider a public producer charges prices not covering actual depreciation of assets, which is, for example, very often the case of public transport companies aiming to keep prices of transport services lower. To illustrate this point numerically, if depreciation of 100 is not included in final prices charged by a public producer, then it is only this 100 that will add to GDP when this company is moved to the general government sector, and the way its products are valued is changed. This implies that even the value of GDP is more or less sensitive to the definition of the general government because of different valuation methods of products of non-government and government institutions.

To sum up, the delimitation of government heavily affects several key macroeconomic indicators, including GDP, thereby affecting business cycle analysis, growth and productivity indicators, the extent of fiscal expansion or contraction as well as ways through which fiscal measures might be conducted.

1.2 Economic research

Mainstream macroeconomics generally recognizes the indispensable role of government in society. Indee...