eBook - ePub

Personality and Intelligence at Work

Exploring and Explaining Individual Differences at Work

Adrian Furnham

This is a test

Share book

- 518 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Personality and Intelligence at Work

Exploring and Explaining Individual Differences at Work

Adrian Furnham

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Personality and Intelligence at Work examines the increasingly controversial role of individual differences in predicting and determining behaviour at work. It combines approaches from organizational psychology and personality theory to critically examine the physical, psychological and psychoanalytic aspects of individual differences, and how they

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Personality and Intelligence at Work an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Personality and Intelligence at Work by Adrian Furnham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Individual differences at work

Introduction

This book is an attempt to provide a critical, comprehensive, and contemporary review of the management science, psychiatric, psychological and sociological literature at the interface of differential and occupational psychology. The focus of the book concerns the role of individual differences, specifically personality and intelligence, in predicting, explaining and maintaining all behaviour at work from accidents and absenteeism to job satisfaction and workplace sabotage.

This area of research has shown a strong resurgence of interest with many albeit rather different books with similar titles. Thus we have Personality at Work (Fontana, 2000); The Owner’s Manual for Personality at Work (Howard & Howard, 2001); the edited Personality and Work (Barrick & Ryan, 2003), as well as Personality and the Fate of Organizations (Hogan, 2006). Each asserts the importance of individual differences in understanding behaviour at work.

One might plot the interest organisational psychologists have had over the last 100 years in individual differences. There could be many criteria: the first is academic books and papers published on the topic; a second is evidence of consultancy where management trainers and advisors have used tests for selection and development to help companies improve their efficiency and effectiveness. Third, one could look at companies and see when, which, and why they used personality tests.

It seems, over the twentieth century, that there were four periods of change. The first was during wars (notably the Great War and the Second World War). With high numbers of conscripted soldiers it is important to determine both their aptitudes and temperament for specialist jobs. Hence, testing is used widely by armies and institutions doing person/job fit. Second, there is always growth of tests when there is great economic decline or change often because the number of job applicants increases. Organisations often find tests a cheap and efficient way of improving their selection decisions. Third, when test publishers come into being and management consultants find tests useful in training and development there is often substantial growth in test usage in business, as both sell tests aggressively. But, fourth, there are also periods when test usage declines. This may occur through a change in the law that, for instance, necessitates tests to show substantial evidence that they are not biased against certain groups. It may also occur if there are high-profile litigation cases where testees successfully sue organisations because of the misuse of tests.

Differential psychology is split very dramatically into two areas that are central to the theme of this book: tests of power (intelligence testing) and tests of preference (personality testing). No one doubts that both personality and intelligence predict education, health and work outcomes. However, these two areas of psychology have until recently not been very clearly integrated (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2005). It is important to understand these two solid foundations of differential psychology as well as how they are related.

The two disciplines of differential psychology

Two presidents of the American Psychological Association pointed out in their state-of-the-art address that there seemed, in psychology, a great division between experimental psychology, which sought to discover universal laws of human behaviour, and correlational psychology, which sought to describe and explain individual differences (Cronbach, 1957).

Cronbach (1957) noted that experimental psychologists are embarrassed and annoyed by individual differences, which they often treat as error variances. Yet, this variability is the very essence of correlational or differential psychology. Thus, we have experimental and personality psychologists with different perspectives and agendas.

Eysenck (1981) pointed out that a science of psychology can not properly function without both branches, which are indispensable to a proper understanding of people. More than that, one cannot properly exist without the other. Individual differences interact in almost every case with experimental and situational factors to produce results profoundly different for individuals of different personalities, different capacities and different motivations. Consequently, he argued, studies in experimental, social, educational, clinical or industrial psychology that do not take into account personality factors (using that term in its widest sense as referring to individual differences in temperament, intelligence, character, attitudes, aptitudes, etc.) inevitably throw away a great deal of potential information, and enlarge the error term in their analysis to an unacceptable degree for scientific progress. Main experimental effects are frequently swamped by interaction effects, and these are lost when we do not include personality in the research design. Conversely, the concepts and laws of experimental psychology are vital to any scientific understanding or interpretation of the results of work in personality. Eysenck believed that if we are to explain the major factors of personality in scientific terms, we must make appeal to the concepts used in experimental and physiological psychology. Only in this way, by the integration of the two disciplines of scientific psychology, he suggested, can we hope to build up a unitary science, as opposed to that “collection of chapter headings” of which William James spoke so disparagingly. Despite the obvious commonsensical nature of this observation the two worlds of correlational and experimental psychology remain steadfastly separated. Whilst there are divisions within each camp, nevertheless there is still mutual distrust and suspicion between these two groups who largely ignore one another.

Differential psychology is itself split into two definable groups: those who study personality traits and those who study intelligence (Table 1.1). Various researchers (Ackerman, 1994; Anastasi, 2004; Eysenck, 1967) have made various conceptual distinctions between the two areas.

The delineation is relatively clear. Intelligence researchers are interested in ability, primary intellectual or cognitive ability, always measured by power tests with right or wrong answers. Intelligence tests are often called cognitive or cognitive ability tests. Nearly all ability tests are timed. Intelligence tests tap into maximal performance to see what a person is capable of. Intelligence researchers are essentially interested in describing the processes and mechanics underlying problem-solving ability.

Table 1.1 The two pillars of differential psychology

Table 1.2 Distinguishing between intelligence and personality

Personality researchers on the other hand look at how people naturally or typically behave. They look at preferences and habitual ways of behaving. They are as much interested in perceptions and emotions as cognitions. Personality tests are rarely timed and often point out that they do not have right or wrong answers.

Most and Zeidner (1995) listed 10 dimensions upon which these two constructs differed (Table 1.2).

The “neat” distinction between the two areas has, of course, attracted the attention of those who are interested in the measuring and explaining of things from the other perspective. Thus, for a long time now, we have had power or objective tests of personality and self-assessed tests of intelligence (see Chapter 7).

There is a long history to objective personality tests. Cattell (1957) defined an objective personality test as any test showing reasonable variability that could be objectively scored and the purpose of which was indecipherable to the subject. Cattell and Warburton (1967) compiled an impressive compendium of over 800 objective personality and motivation tests for use in experimental research. Over the years, various tests have been devised to measure particular traits. Thus, Wallace and Newman (1990) related motor speed (trace on a circle template as slowly as possible) to impulsivity because people high in impulsiveness should be less able to measure their approach behaviour.

There remains an interest in objective personality tests (Karp, 1999) but this research is found more in the applied, clinical literature than the academic, personality area (Cimbolic et al., 1999; Schmidt & Schwenkmezger, 1994; Schwenkmezger et al., 1994).

One reason why objective tests are attractive to researchers is that they supposedly reduce the possibility of faking. Indeed Elliott et al. (1996) demonstrated that an objective test (time taken to trace a circle) is more resistant to failing than self-report personality questionnaires.

The rise in interest in genetic and biological markers of personality may mean a great rise in interest in this sort of measure of personality. Indeed for nearly forty years there has been an interest in the relationship of personality and salivation (Corcoran, 1964; Deary et al., 1988). It may well be that mouth swabs will replace personality questionnaires in the next decade!

Equally recently there has been renewed interest in self-assessed or self-estimated intelligence. There are also questionnaires that measure things such as Typical Intellectual Engagement (TIE; Ackerman & Goff, 1994), which are closely related to measures of intelligence. Indeed it has been suggested that certain personality traits, like Openness-to-Experience, which is associated with curiosity and a life of the mind (i.e. interested in aesthetics, etc.), are proxy measures of intelligence. Some even call the dimension intelletance.

But for the organisational psychologist interested in the topic of assessment and selection, there is an interesting paradox and conundrum. It is essentially whether selection tests are really measures of maximal personality and typical intelligence: assessing people using measures of intelligence and personality to predict job success. Do they respond, as asked typically, on the personality measure? Or do they respond maximally in the sense that they give the most desirable answers. Further, do they, once they have acquired the job, behave maximally according to their ability (Hofstede, 2001; Klehe & Anderson, 2005) or typically according to their usual pace?

It is well known that people dissimulate in any form of self-report measure, be it interview or questionnaire. They try to form a good impression or, worse, perhaps they are completely lacking in self-awareness and self-insight so cannot rather than will not report on their actual beliefs and behaviour. They answer untypically in the sense that they often under-report their neuroticism and over-report their conscientiousness. In fact this is not a serious psychometric problem (Dilchert et al., 2006; Furnham, 1986) from a predictive validity point of view but it does mean that the profile is not typical. By processes of impression management, selective memory, and presentational skills the interviewee turns a test supposedly of typical performance into one of maximal performance.

Equally most people will try hard to “do well” on any cognitive ability test they are confronted with. However, once they have obtained the job it is not always certain that they will exercise the same effort. At work, then, typical performance occurs when: people are unaware that they are being observed or evaluated; people are not consciously trying to do their best; people work over a longer period of time. On the other hand, maximal performance is more likely to occur when: people know they are being evaluated; people understand and accept instructions to maximise effort; people are observed for a short enough time period to keep them focused on the task at hand.

Thus, people can invest full, intermediate or virtually no effort in a task. In this sense we can have typical or maximal personality and intelligence. Nevertheless it is traditional to think of intelligence tests as those requiring maximal performance and personality tests those requiring typical performance.

The relationship between personality and intelligence

As noted above, relatively few researchers have taken an interest in both personality and intelligence. They seem to be attracted to either one or the other area. There are, of course, exceptions like the two great University College London trained psychometricians Hans Eysenck and Raymond B. Cattell.

But over the years there have been numerous essays, chapters and edited books that have attempted to address precisely that issue (Collis & Messick, 2001; Saklofske & Zeidner, 1995).

Zeidner (1995) has argued that there appear to be seven major ways of thinking about the relationship:

- “Intelligence is the independent variable, whereas personality is the dependent variable.

- Intelligence is the dependent variable, whereas personality is the independent variable.

- Intelligence and personality show a bidirectional relationship, with reciprocal determinism existing between the two constructs.

- The observed personality–intelligence relationship is artefactual, with a third extraneous variable responsible for the observed relationship between the constructs.

- Personality is an intervening or ‘nuisance’ variable intervening between the intelligence construct (as input) and manifest level of intelligence (as output, evidenced in intelligence test scores).

- Personality is a moderator variable, moderating the relationship between intelligence and a criterion variable of interest.

- Intelligence is a moderator variable, moderating the relationship between personality and a criterion outcome variable” (p. 316).

It is agreed that it is too simplistic to think of personality and intelligence acting independently on some measurable work-related variable like output. Whilst it could be expected that bright, stable, conscientious people would produce more in relatively complicated jobs it is equally possible that either personality or intelligence acts as a moderator or mediator variable in that relationship.

More recently, researchers have proposed models that specifically examine the relationship between personality and intelligence. They proposed a model that subjectively assessed intelligence at its centre. More recently they asked what personality and intelligence have in common (Chamoro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2006). They proposed seven things: (1) they are both latent psychological constructs; (2) their effects are manifested and observed in behavioural differences between individuals; (3) such differences can be quantified with standardised psychometric instruments; (4) both variables occupy a central position in the history of differential psychology; (5) they are largely genetically determined; (6) individual scores show relatively little variability over the life span; and (7) they are predictors of individual differences in a wide range of outcomes including performance in educational and occupational settings. They proposed a new concept called intellectual competence or the intelligence personality, which is the individual’s capacity to acquire and consolidate knowledge throughout the life-span, which is dependent on ability, personality and self-insight. These factors help to explain the development of ability, how confidence affects this development and how people perform on day-to-day tasks.

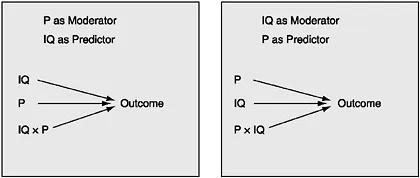

The idea of a moderator and mediator variable can best be described diagrammatically (Figure 1.1).

In this relationship, the direct relationship between intelligence and some outcome variables is mediated by personality. Thus, brighter people might be less productive if very neurotic, but much more productive if very conscientious. In this sense intelligence is moderated by personality. Equally it may be that conscientiousness is moderated by intelligence in that it is only moderately or above average intelligent people who are more productive if they are conscientious.

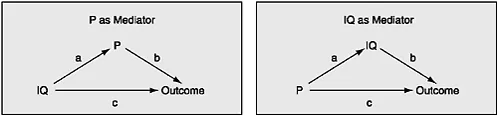

Equally, personality or intelligence could be a mediator variable (Figure 1.2). The important point to note is that any direct relationship between either personality or intelligence at work may be moderated or mediated by the other. In this sense it seems always important to measure both variables in research exercises.

The relationship between personality and intelligence has been explored over the years in single studies as well as meta-analyses. They are not always comparable because they use different measures or systems of personality. Consider the following, the celebrated meta-analysis of Ackerman and Heggestad (1997). It examines the relationship between the Big Five personality variables and five measures of cognitive ability (Table 1.3).

Figure 1.1 Moderator: Third variable that effects zero-order correlations between other two variables.

Figure 1.2 Mediator: When a and b are controlled, previously significant path c is not.

Table 1.3 Personality correlates of psychometric intelligence: The Big Five and ability test scores

Table 1.4 Big Five predictors of fluid intelligence (gf)

It shows five things. First, whatever the measure of cognitive ability used Neuroticism is negatively correlated with all measures: the more neurotic a person, the less well they perform on intelligence tests. Second, extraverts seem to do better than introve...