![]() Part I

Part I

Introduction to Social Research Methods![]()

1

Basic Concepts

When American astronauts landed on the moon in the summer of 1971, their activities included an interesting and, for some, surprising demonstration. They showed that when the effects of atmospheric air friction are eliminated, a light object (a feather) and a heavy object (a hammer) will reach the ground at the same time if dropped simultaneously from the same height. This verification of a basic principle of high school physics delighted many viewers of the live televised broadcast, but probably few of them considered the fact that for hundreds of years before Galileo (who is thought to have originally proposed this process), Western scholars had accepted Aristotle’s hypothesis that heavy objects would always fall faster than lighter ones. For most of us, Aristotle’s assumption seems intuitively correct, even though we now know that it is contrary to scientific theory and demonstrated fact. Not all scientifically demonstrated phenomena contradict “common sense” intuitions in this way, but this case serves to illustrate the difference between science and intuition as bases of understanding the physical and social world.

The emphasis on subjecting all theoretical concepts, hypotheses, and expectations to empirical demonstration—that is, of testing our ideas and observing the outcomes of these tests—is basically what distinguishes the scientific method from other forms of inquiry. The scientific method is a general approach for acquiring knowledge using systematic and objective methods to understand a phenomenon. The scientific method provides an overarching methodological blueprint that outlines the steps useful in conducting such investigations. Its goal is to control for extraneous conditions and variables that might call into question the results of our observation.

In attempting to control the simultaneous release of the feather and hammer, for example, the astronaut was employing a very rough form of the scientific method. Although probably not discernible to the naked eye, both objects were unlikely released at precisely the same the time, so a more carefully controlled and systematic study might drop both objects concurrently by a mechanical claw in a vacuum devoid of air resistance. Observation requires that the outcomes of experimentation be discernible and measurable. If a question is to be addressed using the scientific method, the results of the methods used to answer the question must be observable. The requirement that science deals with observables plays a role in continued scientific advance, as it prods us to continually develop ever more sensitive instruments, methods, and techniques to make observable the formerly invisible. Another advantage is that recorded observational data can be verified by others and at times even witnessed by those who might benefit from the results without having to replicate this study. The astronaut as well as the television audience observed the same outcome of the feather and hammer study, and therefore likely arrived at a similar conclusion, that objects fall at a rate independent of their mass once air friction is eliminated.

Outlining the principles of the scientific method, which lend structure to the procedures used to conduct systematic inquiries into human behavior, is what this book is all about. The book is intended to present the research methods and designs that have been derived from basic principles of the scientific method, and to show how these techniques can be applied appropriately and effectively to the study of human cognition, affect, and behavior in social contexts.

Science and Daily Life

It is important to understand that the research principles and techniques presented throughout this text are not reserved solely for the investigation of major scientific theories. At issue in many instances are questions of purely personal interest—the consensus surrounding one’s beliefs, the relative quality of one’s performance, the wisdom of one’s decisions—and in these circumstances, too, the application of the scientific method can prove useful. At first glance, using scientific methods to guide one’s own decision-making processes (or to judge the quality of their outcome) might appear somewhat extreme; however, in light of much current research on human judgment, which demonstrates the frailty of our decision-making powers, this is a fitting application of research methods, especially when issues of personal consequence have the potential to benefit many others.

For example, the susceptibility of people’s judgmental processes to a host of biasing influences is well documented (e.g., Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982; Sanna & Schwarz, 2006; Wegener, Silva, Petty, & Garcia-Marques, 2012; West & Kenny, 2011). Research suggests that it is risky to depend solely upon one’s own opinions or intuitions in evaluating the quality of a judgment or an attitudinal position. If Aristotle could be fooled, imagine how much more likely it is that we can be mistaken, especially in situations in which we are highly involved. To develop an intuitive grasp of the difficulties that can affect the quality of even simple decisions, consider the following scenario (adapted from Ross, Greene, & House, 1977):

Suppose that while driving through a rural area near your home, you are stopped by a county police officer who informs you that you have been clocked (with radar) at 38 miles per hour in a 25-mph zone. You believe this information to be accurate. After the policeman leaves, you inspect your citation and find that the details on the summons regarding weather, visibility, time, and location of violation are inaccurate. The citation informs you that you must either pay a $200 fine by mail without appearing in court or appear in municipal court within the next two weeks to contest the charge.

- Q1. What would you do? Would you pay the fine or contest the charge? ___Pay ___Contest

- Q2. What would most of your peers do? Do you estimate most of them would pay the fine or contest the charge? ___Pay ___Contest

Now let’s consider your estimates of your peers’ behavior in light of your decision to pay or contest the fine. Did your own personal decision influence your estimate of other people’s decisions? Although you might not think so, considerable research suggests that it probably did (e.g., Askoy & Weesie, 2012; Fabrigar & Krosnick, 1995; Marks & Miller, 1987). In a variation of this study, for example, approximately half of those posed with the speeding scenario said they would opt to pay the fine, whereas the remainder opted to contest it (Ross et al., 1977). However, if you would have paid the $200, there is a good chance that you assumed more of your peers would have done the same. On the other hand, if you would have gone to court, you are more likely to have assumed that your peers would have done so to “beat the rap.” The “false consensus” effect, as this phenomenon has been termed, is an apparently common and relatively ubiquitous judgmental heuristic. In the absence of direct factual information, people tend to use their own personal perspectives to estimate what others would do or think. Such a heuristic, of course, can have a substantial influence on the quality of our assumptions and subsequent behaviors.

Clearly, our decision-making apparatus is far from foolproof. Like Aristotle, we are inclined to rely heavily, perhaps too heavily, on our own insights, feelings, and interpretations, and to assume that other reasonable people would think, feel, and act just as we do. There is no simple solution to such problems, but there is an available alternative, namely, to test our intuitions, opinions, and decisions rather than merely to assume that they are valid or commonly accepted. The means by which we make such decisions are based on learning and understanding how to conduct valid research.

The specific purpose of this first chapter is to acquaint readers with the fundamentals of research using the scientific method, and to introduce several important themes that run throughout the text. There are a number of controversial issues in the philosophy of science—such as the status of induction or the logical framework for theory verification (e.g., Bhaskar, 1978, 1982; Kuhn, 1970; Manicas & Secord, 1983; Popper, 1959, 1963)—but these concerns will be avoided in favor of a more descriptive and explanatory presentation of the “ground rules” of scientific inquiry as agreed to by most social scientists.

Theories and Hypotheses

A theory is formulated based on observations and insights, and consists of a series of tentative premises about ideas and concepts that lay the foundation for empirical research about a phenomenon. It serves as an overarching foundation and worldview for explaining a process. A “good” theory serves as a fountain of possibilities from which researchers may generate a wealth of hypotheses to be tested via the scientific method. Theories provide an inspirational framework to guide research. Usually, in any area of research, competing theories vie to explain the same phenomenon, using different conceptual perspectives. Take for instance the theories striving to understand engagement in health behaviors, which include the Health Belief Model, Social Cognitive Theory, the Theory of Planned Behavior, and Protection Motivation Theory. Although there are distinctions across these theories, some common themes also arise: Three of the theories contain a self-efficacy construct, but how self-efficacy is conceptualized varies considerably among the competing theories (Lippke & Ziegelmann, 2008).

Drawn from implications of a theory, a conceptual hypothesis is a prediction about relationships involving the theoretical constructs, and therefore guides the purpose of a research study. It may be viewed as a prediction about what should happen in a research study. At a finer level of specificity is a research hypothesis, which is an empirical specification of the conceptual hypothesis and is therefore a testable directional prediction about specific relationships in a study. A research question is a non-directional statement about specific relationships in a study that ends with a question mark (“Are people with higher pain management skills more likely to survive after major surgery?”), but the hypothesis is expressed as a directional, but still tentative, statement regarding the anticipated direction of the results (“People with higher pain management skills will be more likely to survive after major surgery”). Although not all hypotheses are drawn from some formally established theory, ideally this should be the case, as doing so may contribute to the accumulation of established scientific knowledge. A theory operates at a relatively abstract level, and therefore is tested only indirectly via the observed data of studies testing research hypotheses generated from the same theory.

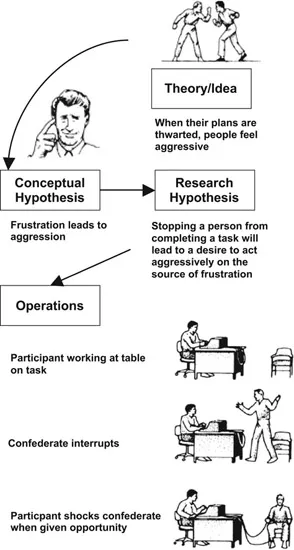

The common feature of all approaches making use of the scientific method, regardless of discipline, is the emphasis on the study of observable phenomena. No matter how abstract the generalization or explanatory conceptualization at the theoretical level, the concepts or ideas under investigation must be reduced to, or translated into, observable manifestations. So, for example, the very rich and complicated concept of aggression as a psychological state might be translated in the research laboratory to participants deciding whether to push a button that delivers an electric shock to another. After “translation” into a form conducive for observation, the very powerful methods of scientific inquiry can be applied to the phenomena of interest. Often, results obtained from these methods suggest that our understanding of the phenomenon was not entirely correct and that we should go back to the drawing board and develop alternative hypotheses. These alternative hypotheses, in turn, are “translated” into a new set of measureable “observables” and the process is repeated, often many times and by many different researchers, for the goal of offering successively better understanding of the topic under investigation. From this perspective, the conduct of scientific inquiry can be viewed as a cyclical process, which progresses from explanation to observation to explanation. From a theory regarding the nature of a phenomenon come deductions (hypotheses), which guide observations, which facilitate refinement of the theory, which in turn fosters the development of new hypotheses, and so forth. We explore the phases of this cyclical progression for scientific inquiry in this first chapter.

From Theory, Concept, or Idea to Operation

Figure 1.1 represents pictorially the translation of theoretical concepts into research operations. In the first phase of the translation process, the researcher’s general theory, concept, or idea is stated specifically in the form of a conceptual hypothesis. There are many ways that such hypotheses are formed, and we consider some of these in the following section.

Generating a Hypothesis

Many factors prompt us to emphasize the importance of theory in the social sciences, and one of the most crucial of these is the role of theory in the development of hypotheses, a process that allows for the continued advancement, refinement, and accumulation of scientifically based knowledge. The development of hypotheses is one of science’s most complex creative processes. As McGuire (1973, 1997) and others (e.g., Jaccard & Jacoby, 2010) have observed, instructors and researchers alike have been reluctant to attempt to teach their students this art, believing it to be so complex as to be beyond instruction. However, by following the lead of some of the field’s most creative researchers, we can learn something about the means that they employ in developing hypotheses.

The most important, straightforward, and certainly the most widely used technique of hypothesis generation involves the logical deduction of expectations from some established theory. The general form of hypothesis deduction from a theory is as follows:

- Theory X implies that A results in B.

Therefore, if the assumptions in theory X are true, a conceptual hypothesis might be generated to anticipate that producing A will result in the occurrence of B. These hypothetical deductions are based on the tentative premises, assumptions, and implications advanced in the theory. Keep in mind that many hypotheses could be creatively generated to test any single theory. Thus, this very same theory might enable the inference of a hypothesis statement for another study proposing that A also produces C.

FIGURE 1.1 Translating a theory or idea into research operations.

A second source of generating a hypothesis arises from conflicting findings in the published research. Typically in this approach, the researcher searches for a condition or observation whose presence or absence helps to explain observed variations or conflicts in findings in an area of investigation. This approach helps to refine theory by testing hypotheses that provide a more strict specification of the conditions under which a particular outcome can be expected to occur (or not to occur).

An example of the use of the “conflicting findings” technique can be seen in research that examined the relationship between ambient temperature and the tendency of people to act aggressively. Experimental research conducted in laboratory settings by Baron and colleagues (e.g., Bell & Baron, 1...