![]()

Section 1

Early Industrial Britain, c1780–1850

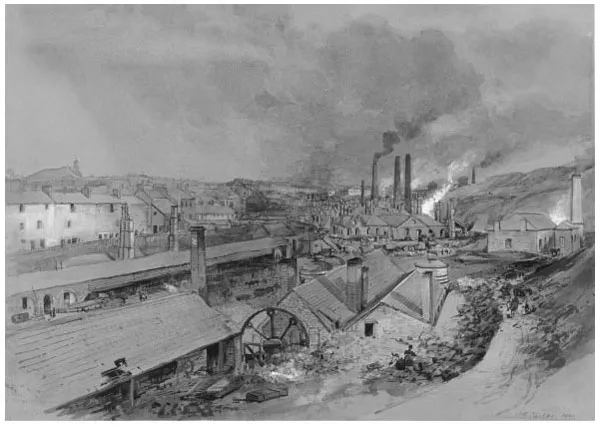

A watercolour by George Childs of the Dowlais Ironworks, Merthyr Tydfil, in 1840

Source: © National Museum Wales/The Bridgeman Art Library

The Dowlais iron works near Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales, originally established in 1759, was by 1845 the largest iron works in the world. Its eighteen blast furnaces were producing almost 90,000 tons of iron a year. It employed almost 9,000 men, most of them, as this picture implies, working in dangerous and unhealthy conditions. Dowlais seems to epitomise the speed of change which transformed Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

To understand the extent to which both society and economy in Britain changed in these years, it is necessary to put such dramatic examples of industrial transformation into a wider context. This Section attempts to explain the factors involved. It begins by discussing (Chapter 1) how the three countries, England, Scotland and Wales, which comprised late eighteenth-century Britain had developed and the extent to which, culturally, they remained separate nations. Chapter 2 discusses the reasons why British population was growing so fast. A growing population was vital for industrial growth, which needed a healthy supply of labour not just for the new factories but also to meet the need for unskilled and semi-skilled labouring tasks. The social and economic roles of the landed aristocracy, which invested heavily in urban development at this time, are examined in Chapter 3, while Chapter 4 explains how, and why, the middle classes became an increasingly important element in British society, even challenging the dominance of the aristocracy in some areas.

Chapters 5 and 6 are concerned with the nature of Britain’s industrial and urban growth. The industrial revolution did not transform all of Britain in this period. Even by 1850 more people worked on the land than in the towns and cities. So, is it appropriate to talk of an ‘industrial revolution’ at all? Perhaps the main changes were evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Towns had very diverse functions. In addition to the great factory communities of south-east Lancashire, the West Riding of Yorkshire and the central valley of Scotland, this was a time of growth and increased prosperity for towns such as Bath and Brighton, whose main economic rationale was leisure and social interaction. Older regional centres such as Bristol and Norwich and market and cathedral towns of England, such as Oxford and Shrewsbury, were also growing significantly.

Chapter 7 examines the continued importance of agriculture. No study of industrial change should ignore the rural sector of the economy, not least because significant changes in agricultural organisation and production were needed to feed a growing population, a smaller proportion of which was growing food. Whether ‘revolutionary’ or ‘evolutionary’, industrial change was massively disruptive. The final chapter of this Section discusses the nature of this disruption. It examines the extent of social conflict in this period and investigates whether, by 1850, Britain had become a society riven by class antagonisms.

![]()

1

A ‘Greater Britain’ in 1780?

I. A costly war

During the period covered by this book, Britain, or the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, its official title after the Act of Union in 1800, was the wealthiest and the most powerful nation in the world. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Britain became not just the workshop but the manufactory of the world, using new technologies to produce a range of manufactured goods, especially textiles, much more quickly and efficiently and also at prices which no competitor could match.

We begin in 1780 because, although strict chronological precision is not attainable, a consensus exists that the pace of Britain’s commercial activity and industrial production, the prime agents of its nineteenth-century supremacy, substantially quickened in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. If supremacy is a key theme in this story, however, 1780 might seem a perplexing date from which to begin. Contemporaries saw it as a time of humiliation abroad and dangerous political conflict at home. Britain had been at war with its thirteen North American colonies since 1775. It was at war with France and Spain from 1778 too, as those countries weighed in on the colonies’ side, once it became clear that British arms would not bring about the rapid victory which had been widely assumed. By 1780, a series of reverses had brought it close to defeat. That defeat, and consequent American independence, would be confirmed by decisive reverses on the battlefield during 1781 and then, formally, by the Treaty of Versailles in 1783. The assumption was that the loss of the colonies would severely damage Britain’s trade routes and commercial activity. One provincial newspaper suggested that the combined might of France and the American colonies would destroy Britain as a naval power.1

The war was also costly. British governments had to find about £80m, which they did by raising loans and substantially increasing the National Debt. Crucially, it also raised taxes, including those on salt, soap and alcohol which fell disproportionately heavily on the poor. Despite this, excise duties, substantially the largest source of government income, fell during the later stages of the war as consumption was squeezed. Over-taxed, poorly governed, resentful and defeated in war, the country appeared to be at its lowest eighteenth-century ebb in the early 1780s.

Excise duties

These are taxes raised on goods sold in the country, in contrast to customs duties which are levied on goods coming into it. These are indirect taxes. This means that they are added to the price of the goods when sold, irrespective of the ability of the purchaser to pay. In the eighteenth century, excises were levied on a wide range of basic items, including salt, beer, soap and candles as well as luxury items such as wine or gold.

The country in question, of course, was ‘Great Britain’, but Britain was a relatively recent creation, comprising the nations of England, Scotland and Wales formally brought together by the Act of Union passed in 1707. It is worth a brief introduction to the nations which comprised Great Britain. England was, of course, the largest of the three nations both geographically and, in particular, demographically. In 1780, it comprised about 78 per cent of Britain’s population, compared with Scotland’s 16 per cent and Wales’s 6 per cent.2 A century later, after substantial industrial development in all three countries, the overall demographic proportions showed little change: England 82 per cent, Scotland 13 per cent, Wales 5 per cent.

England’s overall wealth and current level of economic activity were also much higher, although both the central lowlands of Scotland and parts of South Wales experienced significant commercial and economic development in the second half of the eighteenth century. Critically, the development of agriculture, which employed the majority of the population, proceeded more rapidly during the eighteenth century in England than in either Wales or, allowing for a few exceptions in the Lowlands, Scotland. Many economic historians speak of an English agricultural revolution in the eighteenth century (see Chapter 7). This had significant social consequences. Subsistence farming by small peasant proprietors had been almost eliminated from England by the last quarter of the eighteenth century. By contrast, central and North Wales and the Highlands of Scotland both retained significant numbers of small landowners engaged in subsistence farming. As we shall see, England’s superior overall levels of prosperity persuaded many of its well-heeled citizens that the inhabitants of Wales and Scotland were backward and their countries a deadweight on England.

Subsistence farming

This might best be considered as ‘domestic farming’, as it was usually practised by small proprietors or ‘smallholders’ known as peasants. Its purpose was to provide sufficient food for the family. This form of farming contrasted starkly with agriculture designed to produce crops and animals for the market and, therefore, for profit.

The Scots – more numerous, better educated and a more obvious presence in influential London society than the Welsh – bore the brunt of this opprobrium. For much of the century, the dominant English perception of Scotland was of a barren, backward, poverty-stricken nation. James Boswell, the Edinburgh-born biographer of Dr Samuel Johnson, frequently felt the force of his biting anti-Scottish wit. The definition of oats in Johnson’s 1755 Dictionary as ‘a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but which in Scotland supports the people’ is famous. Boswell was also briskly told that ‘the noblest prospect which a Scotchman ever sees, is the high road that leads him to England’ and that ‘much may be made of a Scotchman, if he be caught young’. Its superior education system notwithstanding, the image of Scotland as an unworthy supplicant at the rich Englishman’s table was widely accepted as plain truth.3 Metropolitan hostility to the Scots was real enough.

II. Wales

Wales had been yoked to England for almost five centuries, having been dominated by the larger country since Edward I’s conquests in the early 1280s. It was formally joined to England by an Act of Union passed in 1536, although it retained some separate legal courts and practices until the Council of Wales was abolished in 1689.4 The judicial system of Wales would finally be assimilated with the English in 1830. Precise calculations of Welsh population are not available but most estimates suggest that it was not greater than half a million in 1780.5

Welsh society revolved around the influence of the few prosperous gentry families who often established links by marriage with English landowners. Most were Tory supporters throughout the eighteenth century, when the government was, until the 1760s, Whig and in the hands of large, and mostly English, landowners.6 Sir Roger Mostyn (1673–1739), for example, married the daughter of Daniel Finch, second Earl of Nottingham, and represented Flintshire in parliament. Sir Watkin Williams Wynn (1693–1749) became the largest landowner in Wales on the occasion of his marriage in 1715 into another prominent Welsh family, the Vaughans. He entered parliament the following year as a staunch Tory who opposed the Hanoverian succession and supported the return of the Stuarts.7 He remained an MP until his death in 1749 and was for a time perhaps the most prominent Tory in the House of Commons during the period of the so-called ‘Whig supremacy’.

Wynn’s elder son (1749–89) – also named Watkin Williams – was a prominent patron of the arts who helped further the London career of the composer George Frederick Handel. In the Commons from 1772, he kept up the family tradition of opposition – in his case to Lord North in the 1770s and the Younger Pitt in the 1780s. Unlike many landowners from the Principality, Wynn made a point of stressing his support for ‘Welshness’ and the upholding of Celtic traditions. He was a generous patron of the London Welsh charity school, which was supported by the Society of Ancient Britons, of which Wynn became Vice-President in 1772.

By 1780, Wales, unlike Scotland or Ireland, had long ceased to be regarded as a threat to England. It retained its own language, of course, but only the lower orders made much use of it. The English dismissed Welsh as a barbarous language befitting only the uncivilised – and then mostly forgot about it. Celtic history, ballads and literature were little studied by the propertied classes and remained to be practised safely by the lower orders on the western side of Offa’s Dyke. Ordinary Welsh working families in the late eighteenth century had few links with their English counterparts. Not until well into the nineteenth did Welsh workers migrate in significant numbers to the larger cities of England – Liverpool, Birmingham and London in particular – to pose any kind of threat to the earning power of their English counterparts.

The Church of England was the established Church of Wales also, although Welsh bishops had low status in the episcopal hierarchy and, in consequence, some of the lowest incomes. During the course of the eighteenth century, nonconformist Churches, particularly Baptist and Methodist, were establishing themselves at the expense of the established Church.

Welsh politics, too, had long since been thoroughly assimilated into the English-dominated parliamentary structure. As the Wynns demonstrated, Welsh MPs might oppose the government of the day, and many Welsh MPs were Tories in an age dominated by the so-called Whig Oligarchy. Some might even be seditious. However, the Welsh gentry did not produce firebrands or tub-thumping orators either capable of, or much interested in, exciting public opinion and raising a crowd. Eighteenth-century Wales did not produce a David Lloyd George (see Chapter 38). Likewise, Welsh nationalism mostly slumbered. In any case, the Principality returned only twenty-four MPs to the House of Commons, less than 5 per cent of its total complement. Few issues indeed turned on what the Welsh thought.

Whig Oligarchy

An oligarchy is a form of government in which a small number of privileged men dominate affairs. This phrase relates to the long period of political dominance exercised over almost half a century by great landowners (most were titled aristocrats) in the Whig party, from the death of the Tory-inclined Queen Anne in 1714 down to the accession of George III in 1760. There was no hard-and-fast ideological or social division between Whigs and Tories in the eighteenth century, although Whig politicians tended to own more land and to have more aristocratic titles than did Tory ones.

III. Scotland

Scotland was different. Its relationships with England had frequently been fractious. Disputes over territory on either side of the border were frequent in the early medieval period, not infrequently spilling over into war. Edward I threatened to do to Scotland what he had done to Wales and might well have succeeded had he not died near Carlisle in 1307 while preparing an invasion of Scotland. Not surprisingly, Scotland established what it called an ‘auld alliance’ with France for much of the early modern period, seeing it as an effective safeguard against a much more powerful neigh-bour. Relations improved somewhat when James VI of Scotland was named as the successor to Elizabeth I. He united the two thrones as James I of England from 1603. United crowns did not make for a united British nation. Charles I attempted to recover his fortunes in the Civil Wars of the 1640s by making an alliance with Scotland against the English parliament.

The so-called ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688–89, which saw the ejection of James II and the installation of the Dutch William III on the throne, catapulted England into wars against Louis XIV of France. These...