- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

At first glance, Jessica Ingram’s landscape photographs could have been made nearly anywhere in the American South: a fenced-in backyard, a dirt road lined by overgrowth, a field grooved with muddy tire prints. These seemingly ordinary places, however, were the sites of pivotal events during the civil rights era, though often there is not a plaque with dates and names to mark their importance. Many of these places are where the bodies of activists, mill workers, store owners, sharecroppers, children and teenagers were murdered or found, victims of racist violence. Images of these places are interspersed with oral histories from victims’ families and investigative journalists, as well as pages from newspapers and FBI files and other ephemera.

With Road Through Midnight, the result of nearly a decade of research and fieldwork, Ingram unlocks powerful and complex histories to reframe these commonplace landscapes as sites of both remembrance and resistance and transforms the way we regard both what has happened and what’s happening now—as the fight for civil rights goes on and memorialization has become the literal subject of contested cultural and societal ground.

With Road Through Midnight, the result of nearly a decade of research and fieldwork, Ingram unlocks powerful and complex histories to reframe these commonplace landscapes as sites of both remembrance and resistance and transforms the way we regard both what has happened and what’s happening now—as the fight for civil rights goes on and memorialization has become the literal subject of contested cultural and societal ground.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Road Through Midnight by Jessica Ingram in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Photography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Preface

This is an interpretive and suggestive work rather than a scholarly one. The history of this country is a racist one, and I wanted to reeducate myself about its creation by illuminating and illustrating histories of violence and resistance, where often there were no cameras or tape recorders. To try to understand an expanded history outside of the dominant and constricted telling, I had to understand the context in which these stories played out. Along with making photographs, I constructed this account by visiting sites that held histories of both racist violence and resistance to it and by assembling archival material from microfiche at local libraries, files at the Southern Poverty Law Center, ephemera kept by family members, and reports gathered by journalists.

I have been conscious of voices, the need to hear directly from those most affected—from family members as well as from journalists and investigators—about the complications of reporting and reopening cold cases from the civil rights era. I interviewed family members who lost loved ones to racist violence, journalists who reported on these events at the time, and those investigating cold cases now. The oral histories have been edited for clarity and concision; in preparation for publishing this book, I went back to those whom I had recorded, with the exception of Stanley Dearman, who passed away, so they could review their stories and give their approval for use in Road Through Midnight.

I am sharing what I have learned and come to know after traveling in these southern places and speaking with people there—how historical proximities and legacies of power are reflected in collective knowledge, in individual experience, and in the landscape. I want the viewer not only to experience these images and histories but also to understand place in relationship to the violence and resistance that happened there.

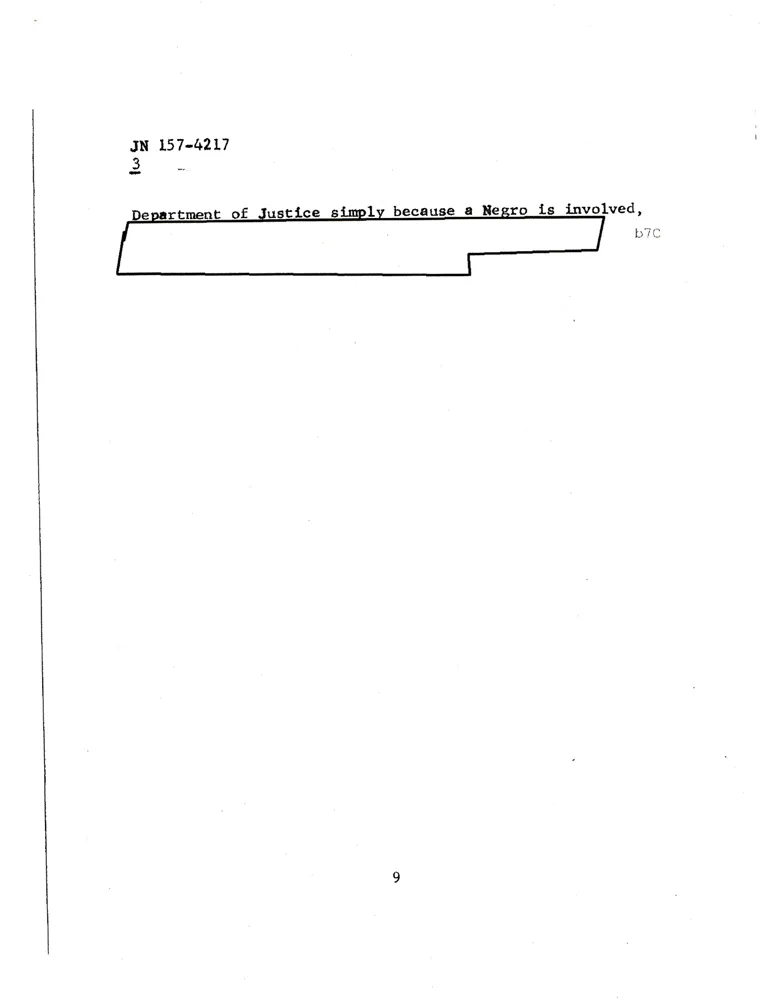

Jimmie Lee Griffith, a twenty-six-year-old man, was murdered September 24, 1965, while walking home from a friend’s house in Sturgis, Mississippi. He was killed in a hit and run; the skid and burn marks on his body indicate that the car backed up over him. Griffith’s suspicious death was investigated at the time by the state and by the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, but there were no indictments. The FBI reopened the case in 2008, after the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act became law, and closed it again in 2012. Page from undated FBI file, courtesy of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

From an Address by Myrlie Evers-Williams to the Crimes of the Civil Rights Era Conference, April 2007

You could hear the footsteps. We were seated, and the guilty verdict was read. How did I feel at that moment? I can honestly say that every bit of anger, every bit of hatred, of fear, escaped from every pore of my body when that verdict was read, and I felt free. But I also felt that America, my people, all people, were freer when that verdict was read.

Reporters from around the world asked questions. “How do you feel?” they asked. All I could say was, “Medgar, I kept my promise. It took thirty-plus years, but I kept my promise. Hopefully others will also benefit from that promise as well.” The fear, the anger, and the willingness to live a full life, all of those things were coming together, and I felt, “I have done my job.”

I kept my promise to Medgar, but my job was not finished, because more needed to be done. As we meet here, and talk about how to go about it, I have another concern. How do we, who have been there, and are dying off now, how do we, those who are the generations behind me, and behind them, transfer the dedication, the knowledge, the appreciation of all that has gone on before, to a generation now where so many see it as something long ago that does not impact them at all.

We not only have to remember the past, we also have to make the link to the next generation coming along. If we don’t, we will find ourselves in another kind of civil war, another kind of horror that we will not know how to take care of. As someone said, community is so important. We must have a sense of that, of protecting our rights, of saying, “One who has will share with one who does not.” And that includes knowledge. A promise was made; a promise was kept.

“Explosion Destroys Negro Home in Ringgold Killing Mother.” Photograph by George Baker, Chattanooga Daily Times. From FBI file dated May 26, 1960, courtesy of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Site of Mattie Green’s home, Ringgold, Georgia, 2009.

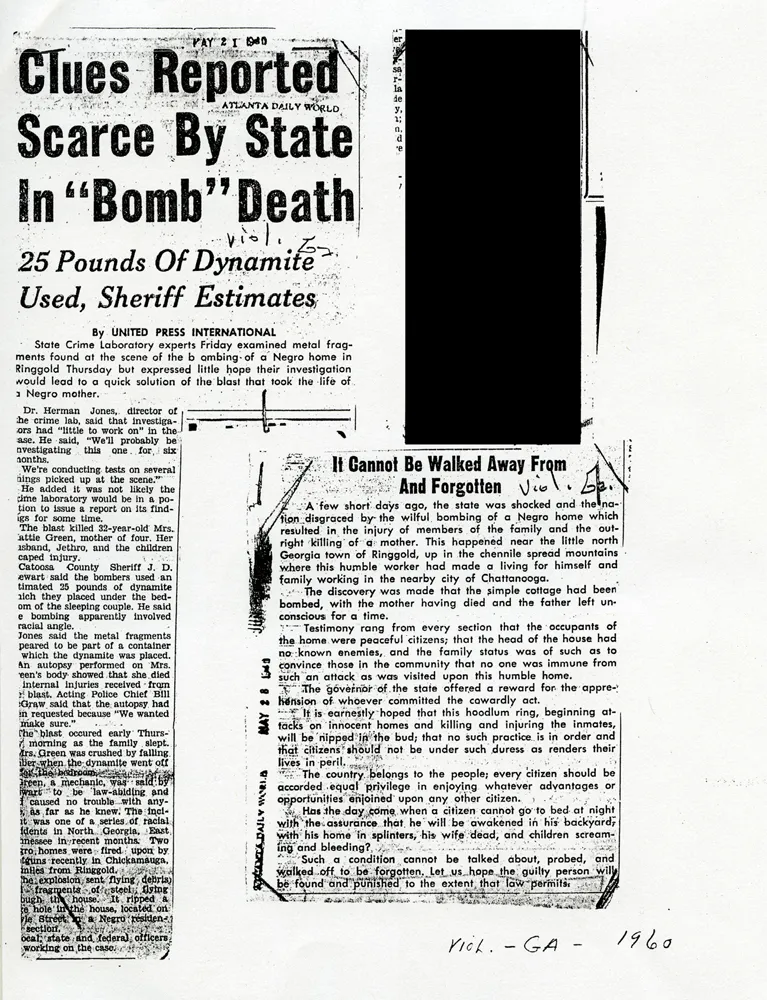

Mattie Green, a thirty-two-year-old mother of six, was murdered when a bomb under her house in Ringgold, Georgia, exploded on May 19, 1960, while she and her family were sleeping. The rest of the family survived. Two daughters, including Anna Ruth Montgomery, were staying at their grandmother’s house a few blocks away. When she heard the explosion, ten-year-old Anna ran home; she remembers seeing her family’s clothes strewn outside. No one was convicted of the crime, and the FBI closed the case after concluding that no federal laws had been violated. Montgomery recollects that the family knew who the murderers were—she remembers when her father, while reading the Sunday obituaries, would tell the family, “Another one’s gone.” When the FBI reopened the case in 2007, Montgomery told them, “Don’t open it if you’re not going to solve it.” The FBI closed the case in 2009 due to a lack of evidence.

Atlanta Daily World, May 21 and 28, 1960. Courtesy of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Law office, Pulaski, Tennessee, 2006.

The Ku Klux Klan was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, on Christmas Eve 1865. The original historical marker, which has since been bolted to the wall backward, reads: “The Ku Klux Klan organized in this, the Law Office of Judge Thomas M. Jones, December 24, 1865. Names of the original organizers Calvin E. Jones, John B. Kennedy, Frank O. McCord, John C. Lester, Richard R. Reed, James R. Crowe.”

Historical marker for Michael Donald, Mobile, Alabama, 2009. “On March 21, 1981, 19-year-old Michael Donald was abducted, beaten, killed and hung from a tree on this street by members of the Ku Klux Klan. He was randomly selected in retaliation for an interracial jury failing to convict a black man for killing a white Birmingham policeman. The lynching was intended to intimidate and threaten blacks. Two Klansmen were arrested and convicted. Morris Dees, cofounder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, and Alabama state Senator Michael Figures filed suit on behalf of Michael Donald’s mother, Beulah Mae Donald. A jury awarded her $7 million, bankrupting the United Klans of America. In 2006, Mobile renamed Herndon Avenue as Michael Donald Avenue.”

Jerry Mitchell

Jackson, Mississippi

June 28, 2010

I’m an investigative reporter for the Clarion-Ledger. I was covering courts in Jackson when I started writing about this stuff, which was in 1989. I had a press pass and went to see the movie Mississippi Burning. The movie itself was very powerful, and I was woefully ignorant about the killings or anything else about the civil rights movement. I saw it with two FBI agents who investigated the case, as well as a journalist who covered it. The FBI agents were Jim Ingram and Roy Moore, who was the head of the FBI in Mississippi, and the journalist Bill Minor.

After the movie, I’m standing there as these old men started talking. They start telling me stuff, you know, and it was the beginning of my education. I was horrified by the fact that none of those guys ever got prosecuted for murder. That just blew my mind. More than twenty people were involved, and nobody was prosecuted for murder.

About a month after that, I’m working the court beat and get a tip. The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission records are all sealed at this point, and I got a tip that some of them had accidentally been included in an open court file. I went up to the courthouse, and there they were. It was a filing by the attorney general’s office, and they had accidentally attached some of the files as an exhibit, and it should have been in the closed court file. I made a quick copy, went back to the paper, and did a story. What the files showed was that the commission had infiltrated this civil rights group here in Jackson and stolen a bunch of photographs and documents on incoming Freedom Summer volunteers, which of course included [James] Chaney, [Andrew] Goodman, and [Michael] Schwerner.

The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission was a state-run segregation spy agency that operated from 1956 up to 1973. In 1977, all those records got sealed by the legislature until 2027. They were finally opened in 1998, but they were still closed during this period of time. That’s what drove me to some extent. I always say, if someone tells me I can’t have something, I want it like a million times worse. So I was like, well, what else is in there? I didn’t set out on day one thinking, I’m going to reopen these cases. I didn’t know that. I was just digging into the Sovereignty Commission, trying to get people to leak me stuff, and I eventually loaded up the back of my Honda hatchback with 2,400 pages of Sovereignty Commission stuff.

One of the leaks showed that at the same time that the state of Mississippi was prosecuting Byron De La Beckwith for the killing of Medgar Evers, this other arm of the state, the Sovereignty Commission, was secretly assisting the defense in trying to get Beckwith acquitted. My story ran on October 1st, 1989.

The trial for Beckwith was 1964. The killing of Medgar Evers was 1963. He was assassinated here in Jackson. That led me.

I called Myrlie Evers and asked if the case should be reopened, and she said yes. And so I did my initial story, then her story, and then we had an editorial calling for the case to be reopened. The Jackson City Council passed a resolution saying the case ought to be reopened. It’s kind of one thing led to another—I always compare it to a snowball at the top of a very tall mountain. It began to gather speed over time, and by the time it hit the bottom, it was an avalanche. Beckwith got indicted. I went and interviewed him. That was an experience.

He was living in Signal Mountain, Tennessee, right outside of Chattanooga. I didn’t go to do a “gotcha” interview. There were a handful of us that got in to talk to him. You had to pass the quiz: Are you white? Who are your parents and where did you grow up? What are their names and where did you go to college? Those kind of things. He loved my answers and so he let me come. My very conservative Christian upbringing came in handy. My background wasn’t that different from his.

I was interested in how he became racist, and I think got the answer. He was an orphan by the time he was aged twelve and he joined everything. He didn’t just join the Klan. He joined the Masons, the Shriners, the Sons of the American Revolution, the Sons of the Confederacy. He had a very deep-seated need to belong. To be fair to Beckwith, it wasn’t like he was an aberration or something; he was very much a part of the white supremacist culture that was all around him. “White supremacist” gives the idea that everybody’s got Klan hats on. A better description of it is a white segregationist, paternalistic view where every white, no matter how low on the totem pole, is above any black. And that’s the way that Beckwith thinks. So he joins the Klan.

Beckwith was one of those men who wanted to be something. He never was anything before, and I think he thought he would be championed. You know, that whoever did it would be championed. He didn’t want to make it publicly known, but he was certainly happy to let people know privately that he did it. There were like six witnesses at trial that he had supposedly bragged to.

This has become, for lack of a better term, my mission. It’s been called “ghosts of Mississippi,” and it is. I mean, the ghosts of these people. It’s a haunted state, unfortunately. We led the nation in the number of African Americans who were lynched between Reconstruction and the civil rights movement. If you take a map of where Klan violence was the worst during Reconstruction days, and you overlay it with where Klan violence was the worst in the ’60s, it’s virtually identical. The eastern prairie, and Meridian and Philadelphia, and ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright Page