![]()

Part I

1613

![]()

1

England in 1613

Our first moment is then 1613. It opened with the marriage of Elizabeth, daughter of King James I, to the Elector Palatine, Frederick V; celebrations to include a sequence of spectacular masques at various Inns of Court, complemented by screeds of verse, the most impressive of which was John Donne’s Epithalamium. And just possibly a final Shakespearean play; a thought to which we will return shortly. The marriage assumes a greater significance in the longer history of the British monarchy. A century on, it was Elizabeth’s grandson George who would accept the invitation to come over and become the first of the Hanoverian Kings; in preference to any number of conspicuously Catholic Stuart claimants.

What else happened in 1613? Sir Thomas Overbury vomited himself to death in the Tower of London. The subsequent scandal which unfolded during the trial of his alleged murderers painted an unseemly picture of life at the Jacobean Court. It also came dangerously close to implicating the King. James, meanwhile, was busy writing. A man of many opinions, with a propensity for publishing them; discourses on kingship, instruction manuals on witchcraft, commentaries on the dangers of smoking tobacco. In the summer of 1613 he issued a Royal Proclamation Against Private Challenges and Combats; which everyone ignored. They could not so easily ignore his essays on kingship though. Something else that happened in 1613 was the transfer of Sir Edward Coke, from the Court of Common Pleas to the King’s Bench, where he assumed the office of Lord Chief Justice. It was part of a long-running and increasingly dangerous feud, between the King and his most senior jurist. We will see how all of this played out in the coming pages.

First though we should turn the clock back three-quarters of a century, and visit some pretty ruins. The English love a ruin. Thousands of hours each summer spent wandering around manicured rubble. We will visit plenty more in the coming chapters. But for now we will visit two. The first, located a few miles south-east of Farnham, on the banks of the Wey, is Waverley Abbey. The first Cistercian Abbey to be built in England, in 1128. Four hundred and eight years later, King Henry VIII’s Commissioners turned up for a ‘visitation’ and shut it. There was no great fuss. The Abbey was recorded as being ‘slenderly endowed’, with just 13 monks in residence and an annual income of £174 8 3. By the terms of the 1536 Act of Dissolution, the smaller monasteries, with annual incomes of less than £200, went first. The estate was sold to Sir William Fitzherbert, Treasurer of the King’s Household. In 1723 the estate would be purchased by Sir John Aislabie. We will revisit Sir John in a very different circumstance in a later chapter; one moment Chancellor of the Exchequer, the next moment imprisoned in the Tower of London. He built a large house at Waverley, a beautiful garden and a very big lake. It was the fashion.

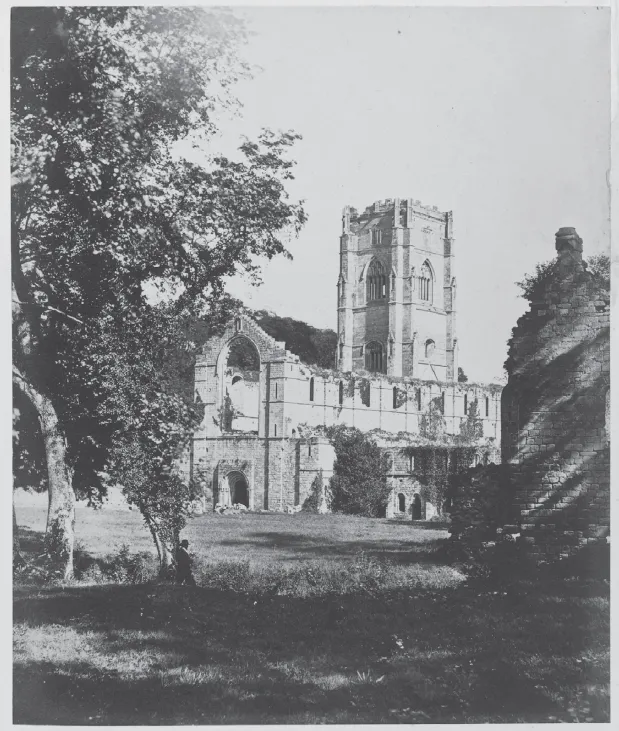

Two hundred and fifty miles to the north was another Aislabie estate, at Studley Royal near Ripon. Sir John inherited Studley Royal in 1693. In 1767 his son William would pay £16,000 to buy the adjoining remains of Fountains Abbey. So that he could construct an even bigger garden, with an even bigger lake. The landscape engineers were called in to dam the neighbouring river Skell, and before long there was not only a canal and a lake, but also some ‘moon’ ponds, a Temple of Piety and an array of Gothic follies. Fountains is the second of our ruined abbeys. Founded shortly after Waverley, in 1132, it was, by the time of its dissolution, the wealthiest monastery in England; recorded as having an annual income of £1,115 and an interest in 138 parishes, manors and tithings, along with various other valuable trinkets, including a piece of the ‘true cross’. Much of the wealth was founded on wool and lead; common industries in the Dales. And the monks had invested well; money begat money. There was over 5000 acres for the Crown to purloin in 1539, much of which was purchased by Sir Richard Gresham, the former Lord Mayor of London, who promptly stripped it down. It was re-used to build nearby Fountains Hall, and later Studley Royal itself; a rather more genteel kind of pillage. As for the monks, and the Commissioners recorded around 40 still pottering about, career options were limited. The least good was rebelling. It was however the choice made by the former Abbot, William Thirske. Thirske had been removed in 1535, on the grounds of ‘immodesty’. Evidently aggrieved, he had joined the 1536 Pilgrimage of Grace and ended up at Tyburn as a consequence; swinging beside his friend, the Abbot of nearby Jervaulx, each with their genitals torn off. Better was the choice made by his successor, Abbot Bradley, who apparently spent his retirement hunting and hawking.

The Reformation changed everything. Not just how the English prayed, but how they did business, how they were governed. Put simply, it made the English nation-state. It also made the English grumpy, and litigious. We might return to 1613, more precisely to the evening of the 29th June. It was on this day that the Globe theatre burned down, during a performance of Shakespeare’s Famous History of the Life of King Henry VIII. We will revisit the play and the performance shortly. Absent the battles, and much that could be said to be either comic or tragic, Henry VIII can seem rather dull fare. If we had started our history in 1485, we could have played with The Tragedy of Richard III. Far more fun. The story of the demented Richard of York murdering his way to the throne before getting his just desserts on Bosworth Field. Henry VIII tells a rather different story; of the moment when, as Bede long ago predicted, the gens Angolorum would prove themselves to be a ‘chosen people’. It should have been a moment of celebration and reassurance. Proof, if needed, that God was indeed English. But somehow it did not feel that way. Not in 1539, not in 1613. And not in 1631 either. In a predictably fawning sermon given before King Charles I that year, Archbishop William Laud wondered why the nation did not seem to ‘know and understand its own happiness’. Many would have supposed it was because of him. Charles, however, looked further back. ‘The Devil take him’, Charles was heard to mutter on receiving Parliament’s Grand Remonstrance in 1641, ‘whosever he be, that had a design to change religion’ (Cressy 2015: 19; Russell 1990: 83).

Image 1.1 Fountains Abbey, c.1850.

A Chosen People

For now, though, we will follow Shakespeare’s lead, and return to the England of Henry VIII. More precisely, we will return to Christmas Eve 1545. Henry is addressing his Parliament, for the last time as it turned out. Two years later he was dead, his soul commended, rather hopefully it might be thought, to the care of the Virgin Mary and a couple of other intercessory saints. Christmas it might have been. But there was not a lot of festive spirit about. On the contrary, there were so many ‘fantastical opinions and vain expositions’ now to be heard in every ‘alehouse and tavern’. God had never been ‘less reverenced, honoured and served’ (MacCulloch 1996: 348; Scarisbrick 1997: 471). He could not go on; it was too upsetting. But he was, in closing, anxious to reiterate one thing. It was not his fault.

Image 1.2 Henry VIII. Engraving by Cornelis Massys, c.1547.

The Reformation Settlement

So whose fault was it? The Reformation might have been ordained by God; but it was written up by lawyers. The monastic clerisy dispersed, some hawking, some hanged, there was anyway no one else to run the country. The idea of a ‘revolution in government’ was famously suggested by Sir Geoffrey Elton, the sheer scale of Reformation requiring an administrative competence far beyond the capacity of a late medieval royal household. More particularly, Elton attributed the ‘revolution’ to the assiduity of Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s Chancellor between 1533 and 1540 (Elton 1953; 1986: 34). A barrister, who began his career representing litigious merchants, Cromwell had entered government as Cardinal Wolsey’s legal adviser in the early 1520s. The Dissolution of the Monasteries, if not quite the Reformation itself, was his idea. And being a lawyer, Cromwell was inclined to make it all very legal. Looking back from 1602, all the antiquarian William Lambarde could see was ‘stacks of statutes’. The reach of Reformation government would run deep. In due course we will encounter the army of provincial justices tasked with keeping the ‘chosen’ people in line. They were busy men. Our present concern, though, is with the statutes which were chased through Parliament in the wake of Henry’s momentous decision to divorce his first wife and marry his second, in January 1533.

The pace was breathless. The first Reformation statute arrived in the March, entitled an Act in Restraint of Appeals. Any appeal made from a decision in an English court to the ‘Bishop of Rome’ would ‘incur and run into the dangers and pains, and penalties contained and limited in the Acts of Provision and Praemunire’. The latter had been around since 1392. So hardly unfamiliar. But never perhaps so pertinent. Anyone reckless enough to approach Rome or obey any papal instruction on the ‘great matter’ of the King’s marriage would know what to expect. The principle ‘penalties’ were escheat, the confiscation of chattels, and imprisonment at the ‘king’s pleasure’. In the coming chapters, we will encounter a series of constitutional statutes which are sometimes termed ‘fundamental’. Some are more recent, some rather older; the Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights, the ‘Great’ Reform Act. The Act in Restraint of Appeals is another. Not as renowned perhaps. But it founded the Anglo-British state.

Meanwhile, faced with the threat of corporate praemunire proceedings, Convocation had made humble ‘Submission’, and offered up a subsidy of £100,000. Parliament was cowed too. And Henry got his divorce. Which meant that he could marry Anne, twice; a sequence of events that we will revisit shortly. And in September 1533 Princess Elizabeth was born. Which meant more drafting. In March 1534 Parliament passed what would become the first Succession Act. It made Elizabeth the lawful heir to the Crown, bastardising her elder half-sister Mary. In the November came a further Act Respecting the Oath to the Succession. Cromwell’s idea, designed to flush out the recalcitrant. Needless to say the King’s propensity for marrying required some later adjustments to the succession statutes. A second Act of June 1536, following the fall of Anne Boleyn, duly bastardised Elizabeth. A third Succession Act of 1543 tried to tidy things up a bit, restoring a natural line, from Prince Edward to Princess Mary to Princess Elizabeth.

Early 1534 also saw the enactment of a couple of statutes intended to deal with financial matters. An Act Concerning Peter’s Pence and Dispensations was as much gestural. ‘Peter’s Pence’ was an annual levy collected by the parish, and sent to Rome; the name deriving from the rating, a penny a hearth. By custom limited to £200 in total, abolition was intended to aggravate the Pope rather than reduce his bankers to tears. The Act Concerning Ecclesiastical Appointments and the Absolute Restraint of Annates mattered more. Annates were annual payments made by the English Church direct to Rome, and could be counted in thousands rather than hundreds. An Act in Conditional Restraint of Annates had suspended payment two years earlier. The 1534 Act abolished it entirely. It did not though end the tax. Revenue was simply diverted to the Exchequer. A further tax statute was passed early in the following year, for the receipt of First Fruits and Tenths. We will revisit these statutes in a later chapter, as we will other significant statutes in the history of English property and inheritance law; the 1535 Statute of Uses and the 1540 Statute of Wills. Between 1536 and 1539 the Crown had acquired around a third of the property of England, with a capitalised value of around £140,000.

In the meantime, we should turn our attention to the end of 1534 and the passage of what would be the centrepiece of the constitutional settlement, the Act of Supremacy. There were in fact two Acts of Supremacy; a second would come in early 1559. The first Act confirmed Henry VIII as the ‘Supreme Head’ of the newly established Church of England, vested with authority to ‘repress’ all ‘errors, heresies… and enormities’. The second Act, necessary because of the repeal of the first by Mary Tudor in 1554, re-established Queen Elizabeth as the ‘Supreme Governor’. The Acts confirmed that the respective monarchs would, as a consequence of their new found ‘dignity’, enjoy ‘all honours, dignities, pre-eminences, jurisdictions, privileges, authorities, immunities, profits, and commodities to the said dignity’ (1534/1559). Everything that had formerly vested in Rome vested in the person of the king or queen of England; the honour, the law, the money.

Image 1.3 Thomas Cromwell. Engraving by Jacobus Houbraken, after Hans Holbein, 1739.

The question of sanction remained. Any who refused the oath of succession or otherwise denied the ‘supremacy’ of the King could be prosecuted by Act of Attainder. Another instrument derived from the later middle ages, an attainder cast the accused beyond the protection of the common law, leaving their guilt to be determined by Parliament alone. Cromwell made frequent recourse to Attainder Acts during the 1530s. Before falling victim himself in 1540, ‘stricken with his own staff’, as the Earl of Surrey remarked (Hiscock 2011: 55).1 A century on, as we will see, the process would become fashionable again; used by the Long Parliament against various allies of Charles I. In the meantime, Cromwell pushed through a new Treason Act. Broadening the provisions of the existing 1351 Act to include any who ‘do maliciously wish, will or desire by words of writing, or by craft imagine, practice or attempt bodily harm’ against the King

or to deprive them of any of their dignity, title or some of their royal estates, or slanderously and maliciously publish and pronounce, by express writing or words, that the King should be a heretic, schismatic, tyrant, infidel or usurper of the crown.2

Amongst the higher-profile victims of Cromwell’s strategy were Sir Thomas More, former Lord Chancellor, and Bishop John Fisher of Rochester. Having declined to subscribe the Oath of Succession, both were named in the Attainder Act of March 1534, before being prosecuted under the terms of the new Treason Act.3 Dealing with the recalcitrant was also the motivation for the Act Extinguishing the Authority of the Bishop of Rome, passed in 1536. Here again the concern was those who ‘by writing, ciphering, printing or teaching, deed or act, obstinately or maliciously hold or stand with to extol, set forth, maintain or defend the authority, jurisdiction or power of the Bishop of Rome’. We will, in due course, take a closer look at the criminal consequence of writing the wrong things. Or just ‘imagining’ them. The indictment laid against More made reference to his ‘silence on the matter of the supremacy’. More strenuously denied that his saying nothing could be deemed, in law, to be ‘malicious’ (Ackroyd 1998: 382–84). But he was wrong.

1536 also saw the first of two Dissolution Acts. Cromwell’s commissioners had been sniffing round the monasteries for a while. In 1534 a smaller group of ‘visitors’ had been despatched to investigate the crisis, material and spiritual, which was apparently engulfing England’s monasteries. They had returned with various tales of leaky chancels and dreadful monastic behaviour. An abbey full of ‘dyvelisshe monkes’ was discovered in Sussex, necessarily ‘past amendment’. Whilst up in Yorkshire, where ‘rudenes’ appeared to be the norm, there were ‘abusys detestable of all sortes’ (Borman 2014: 201–202). Appointed Vicar-General in early 1535, Cromwell had commissioned a survey of monastic estates entitled the Valor Ecclesiasticus, to be completed by suitably supportive magistrates and sheriffs; a ‘profit and loss’ of saving souls and stripping chancels. Estimated values of each estate were returned; a considerable number, happily enough, coming in at just under £200 a year. Fortunate because the 1536 Act, as we have already noted, authorised the suppression of all ‘lesser’ monasteries valued thus. If any valuation was inaccurate a monastery could pay a fine to prove so. A few did. However, 243 monasteries did not.

The first wave of dissolutions realised around £100,000 for the Treasury, together with an annual income of about £32,000.4 To accommodate the sudden influx of estate and profit, Cromwell established an audit office called the Court of Augmentation. A second Dissolution Act, of 1539, legalised the closure of all remaining monasteries. It was under the terms of the 1539 Act that Fountains Abbey was shut down. By spring 1540 every monastery in the land had been dissolved. There were occasional protests. The monks of Hexham managed to get themselves hanged en masse for joining the same futile protest as the Abbots of Fountains and Jervaulx. But the spirit of monastic England was broken. Most went quietly, token gratuities in hand. The Imperial ambassador reported their ‘lamentable’ condition to his master Charles V, describing a ‘legion’ of ‘wandering’ monks going from town to town begging for food (ibid: 265–66).

Meanwhile the sales had started. There was no need to advertise. The word spread and there wa...