eBook - ePub

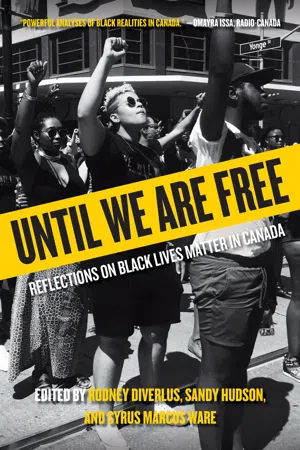

Until We Are Free

Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Until We Are Free

Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada

About this book

The killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012 by a white assailant inspired the Black Lives Matter movement, which quickly spread outside the borders of the United States. The movement's message found fertile ground in Canada, where Black activists speak of generations of injustice and continue the work of the Black liberators who have come before them.

Until We Are Free contains some of the very best writing on the hottest issues facing the Black community in Canada. It describes the latest developments in Canadian Black activism, organizing efforts through the use of social media, Black-Indigenous alliances, and more.

Contributors include:

- Silvia Argentina Arauz - Toronto, ON

- Leanne Betasamosake Simpson - Toronto, ON

- Patrisse Cullors - Los Angeles, CA

- Giselle Dias - Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON

- OmiSoore Dryden - Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS

- Paige Galette - Whitehorse, YK

- Dana Inkster - University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB

- Sarah Jama - Hamilton, ON

- El Jones - Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax, NS

- Anique Jordan - Toronto, ON

- Dr. Naila Keleta Mae - University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON

- Janaya Khan - Los Angeles, CA

- Gilary Massa - York University, Toronto, ON

- Robyn Maynard - University of Toronto, Toronto, ON

- QueenTite Opaleke - Toronto, ON

- Randolph Riley - Halifax, NS

- Camille Turner - York University, Toronto, ON

- Ravyn Wngz - Toronto, ON

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Until We Are Free by Rodney Diverlus,Sandy Hudson,Syrus Marcus Ware, Rodney Diverlus, Sandy Hudson, Syrus Marcus Ware in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Regina PressYear

2020Print ISBN

9780889776944, 9780889777361eBook ISBN

9780889776982PART I

Framing Our Own Story: Black Lives Matter in Canada, Then and Now

1

The Origin Story of Black Lives Matter Canada

Sandy Hudson and Rodney Diverlus

Black Lives Matter—Toronto’s origin story is equal parts rapid response, solidarity actions, community-driven rage, and timing. It’s a story of happenstance, momentum, and seizing a once-in-a-generation opportunity. It’s a story that has been told by several outside of the organization based on what they think they know and what they have been able to surmise based on their observations. But for this project we give you our origin story from the vantage point of the creators and document for all of you what is possible when a community comes together in rage and in a commitment to liberation.

Framing the Moment: A Prelude

On July 13, 2013, the world watched with bated breath as George Zimmerman was acquitted in Sanford, Florida, for the murder of Trayvon Martin. A jury found no fault in Zimmerman, the cretin who shot the unarmed teenager. That night we watched the news as it broke. In our respective homes we scoured the Internet and digested think pieces, commentary, tweets, and spent the night taking in the collective shock felt across the globe. Flurries of texts were exchanged with our friends. Our people were in a state of shock. It was common knowledge that, historically, police were rarely, if ever, found guilty when they killed Black people. But surely, we all thought, this case would be different. For many of us in our twenties, this was the first time that we witnessed sustained public interest in addressing anti-Black violence. Most of us were young children when Rodney King’s beating was headline news, and twenty-two years later, we hoped something would be different; we longed for justice.

We saw ourselves in Trayvon. We too could have been Trayvon. He deserved better. He deserved life. The day after, sleep-deprived and numb, there was a small community gathering and vigil held in Riverdale Park in Toronto. The invitation was kept mostly to extended social media networks, and for many of us following the case, coming together was the only thing we could do. Strangers came together to hold space and time for Trayvon, for our children.

In the year following Trayvon’s shooting, the case had gone from an issue localized within the Black American community to headline-grabbing news. The injustices in the Trayvon Martin case were being discussed across media platforms, trickling up to the Canadian news cycle. This case captured the public’s attention and triggered a global discourse on anti-Black violence not seen in a generation. Suddenly there were think pieces on the disproportionate rate of police violence against Black people that exposed the reality of how many of us were dying at the hands of police. With America’s anti-Black and deeply racist dirty laundry aired out, a global audience of Black and non-Black people tweeted, shared, wrote, and reflected on the case and, more broadly, the realities of living while Black.

This was never just about Trayvon Martin and Zimmerman. The fervour on both sides of the debate was indicative of a more complex system of issues impacting Black people in the United States, Canada, and throughout the African diaspora. Cultural commentators were making the links between Martin and the legacy of North America’s chattel slavery; Jim Crow laws in the United States continued investment in prison cages, disenfranchisement, and the “wars” on drugs, gangs, and guns—the accepted rhetoric for what is really a war on Black people. Zimmerman represented the deep-seated anti-Black attitudes enshrined in North American culture; he was the new face of white supremacy.

Black people in Canada are familiar with these realities. We too experience anti-Blackness across institutions. Police violence and anti-Black attitudes are realities that define the Black experience in Canada. We all remember our parent’s conversations with us about racism when we were children. These conversations are repeated at dinner tables across the diaspora: “Work twice as hard as your white friends to get half of what they will get.” “Be alert and careful around the police; they are not your friends.” To be Black means having a deep understanding of the precarity of living in societies built on anti-Blackness, thriving off the exploitation, control, and disposal of our whole selves.

On the day of the Zimmerman verdict, there was rage. We were heartbroken, disillusioned, stunned; we grieved for Martin’s family and community, our respective families, our communities.

We sat in the grass and listened to speaker after speaker draw on their experiences with anti-Blackness; some of us familiar, many of us strangers. The reality was that the analysis was there, the anger was there. We knew that police violence was not relegated to the United States. We knew about the impacts of anti-Black violence in our own communities. Mothers spoke for their sons and, sadly, we knew that Martin’s fate could also be ours. We knew the crux of the issues but lacked the vehicle through which we could harness and channel our rage. After the vigil we dispersed back to our respective communities.

While we sat in the park, grappling with the verdict, Alicia Garza, 4,000 kilometres away in Oakland, California, was also reflecting on this moment. Sitting at a local bar with friends,1 she wrote an open letter of love to Black people, in which she said, “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter, Black Lives Matter.”2 Patrisse Khan-Cullors took the last three words and put a hashtag on it: #BlackLivesMatter. Unbeknownst to them, they were about to create a global movement.

Over the next year, #BlackLivesMatter grew from a viral hashtag to an online platform. Garza and Khan-Cullors, along with New York organizer Opal Tometi, went on to create the skeletal framework for the Black Lives Matter organization. The platform captured a global community’s imagination and became a viral space to house our collective rage. For the next year, activists, community members, media, pundits, and politicians alike would use #BlackLivesMatter as a lens through which to understand the political, cultural, and historical moment of the day. Those three words captured what many of us couldn’t articulate, a rallying cry heard by Black people across the globe.

One year later it is August 2014, and once again the death of an unarmed Black American teenager grabbed international headlines. Mike Brown was killed by police officer Darren Wilson on August 9, 2014, in Ferguson, Missouri.3 Akin to Martin, Brown’s killing sparked a fury of rallies and protests. The small town of Ferguson became ground zero for an uprising. With Trayvon Martin’s murder still fresh in our collective memory, Black communities across North America reached their boiling point. At the time Black Lives Matter, a loose coalition of American freedom fighters, organized a Freedom Ride to Ferguson. Busloads of freedom fighters descended onto Ferguson to lend solidarity and support to the Black people of Ferguson, then engaged in continuous protests. On some of these buses were Torontonian Black and non-Black activists, educators, students, community organizers, and general community folks who were compelled to do something. The coming months brought more actions, more think pieces, and more people utilizing Black Lives Matter as a mantra to rally behind.

In mid-November a global call for solidarity came from the activists on the ground in Ferguson. A grand jury was deliberating on whether charges would be laid against Officer Darren Wilson in Mike Brown’s murder. In anticipation of an indictment, communities were encouraged to host solidarity actions twenty-four hours after the jury delivered their decision.

From Seed to Fruit: Capitalizing on a Moment

On November 17, 2014, Sandy Hudson sent a message to a cluster of organizers within the city of Toronto:

Friends, a no-indictment decision for Darren Wilson in the murder of Mike Brown is expected any day now. I am wondering if anyone is aware of solidarity actions being planned in Toronto. If not, I think we should do what we can to plan something.

One by one, with no questions asked, voices of affirmation rang in. Many of us were eager to take action, eager to harness our growing rage. We began brainstorming and discussing options. Included in that message were other Black people in Toronto we had organized with in the past, including some who would go on to be core organisers of Black Lives Matter—Toronto: Yusra Khogali, Janaya Khan, Pascale Diverlus, and many other comrades and community leaders. Off the bat, it became important for us to create not just a space for solidarity, but one that centred the experience of Black communities in Canada, that uplifted the local stories not grabbing headlines. We wanted to create a space where all our issues, be it carceral violence or the terrorizing of our communities by TAVIS—the Toronto Anti-Violence Intervention Strategy—could be challenged. We were enraged by the homicide of Jermaine Carby, a twenty-four-year-old Black man from Brampton, Ontario, who was killed by Peel Regional Police officer Ryan Reid.4 We were seeking to rupture the violent way that Canada attempts to absent us; it was a radical, geographic shift in our understandings of Blackness in the Americas.

But the radical, geographic shift was not a new one. It was informed by the internationalist insistences of our ancestors, who insisted upon a global refusal to succumb to anti-Blackness and white supremacy in the abolitionist organizing of the emancipation struggle, the pan-African internationalism of the mid-cent...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: The Year 2055 C.E.—An Imagined Future

- Part I Framing Our Own Story: Black Lives Matter in Canada, Then and Now

- Part II Carceral Violence: Blackness, Borders, and Confinement in Canada

- Part III Creative Activisms: Arts in the Movement

- Part IV Theorizing Blackness: Considerations through Time and Space

- Part V And Beyond: Black Futurities and Possible Ways Forward

- Conclusion: The Palimpsest

- Postscript: The Year 2092 C.E.—An Imagined Future, Part 2

- Contributors

- Editors