![]()

CHAPTER 1

Central Issues in New Literacies and New Literacies Research

JULIE COIRO

UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND, USA

MICHELE KNOBEL

MONTCLAIR STATE UNIVERSITY, USA

COLIN LANKSHEAR

JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY, AUSTRALIA

DONALD J. LEU

UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT, USA

The Handbook of Research in New Literacies explores an increasingly urgent question for educational research: How do the Internet and other information and communication technologies (ICTs) alter the nature of literacy? The answers are likely to provide some of the most important insights about our literacy lives that we may acquire during this century. The answers will also be some of the hardest to obtain, largely because we currently lack adequate theories, constructs, and methods to match the complexity of the question. This volume begins the important work required to integrate the many insights found in multiple lines of research so that we might explore this question in all of the richness and complexity that it deserves.

We seek to advance the study of new literacies by bringing together, for the first time, research taking place around the world in widely diverse disciplines, with even more diverse theoretical frameworks and still more diverse epistemological approaches. Some might see this diversity as a limitation in establishing a common research base; we see it as a powerful advantage. The richness of these multiple perspectives provides us with the best opportunity to understand fully the many issues associated with the changing nature of literacy. We also see in this understanding the best opportunity to help individuals fully realize their potential as global citizens in the 21st century. Our goal with this volume is to begin constructing a foundation on which to begin the important development of the theories, constructs, and methods that will allow us to more thoughtfully study the new literacies emerging with the Internet and other ICTs.

At the beginning, it is essential to acknowledge that the question framing this volume has not suddenly appeared, independent of previous work. As with any good question, this one has an important evolutionary history that should be recognized to understand both where we started and where we are headed. An early version of the question first emerged when precursors to personal computers forced us to confront the possibility that digital technologies might be as much about literacy as they are about technology (e.g., Atkinson & Hansen, 1966–1967).

Following this initial work, a subsequent explosion of personal computing technologies quickly attracted the interest of scholars and researchers with interests in language and literacy. Philosophers, literary scholars, linguists, educational theorists, and educational researchers, among others, pondered the implications of the shift from page to screen for text composition and comprehension (e.g., Bolter, 1991; Heim, 1987; Landow, 1992). They also considered the potential for linguistic theory and literacy education (e.g., Bruce & Michaels, 1987; Reinking, 1988). Questions were raised about the extent to which new technologies altered certain fundamentals of language and literacy and, if so, in what ways and with what consequences. At the same time, some questioned whether there was really anything new to the literacies required by digital technologies or whether digital technologies had simply become the latest tools to accomplish social practices common through the centuries, including reading and writing (Cohen, 1987; Cuban, 1986; Hodas, 1993). Was there really anything new to literacy when the tools change and we simply read and write text on a screen instead of on paper?

The Internet: Unprecedented Dimensions to Both the Speed and Scale of Change in the Technologies of Literacy

The Internet, however, has brought unprecedented dimensions to both the speed and the scale of change in the technologies for literacy, forcing us to directly confront the issue of new literacies. No previous technology for literacy has been adopted by so many, in so many different places, in such a short period, and with such profound consequences. No previous technology for literacy permits the immediate dissemination of even newer technologies of literacy to every person on the Internet by connecting to a single link on a screen. Finally, no previous technology for literacy has provided access to so much information that is so useful, to so many people, in the history of the world. The sudden appearance of a new technology for literacy as powerful as the Internet has required us to look at the issue of new literacies with fresh lenses. The speed and scale of this change has been breathtaking.

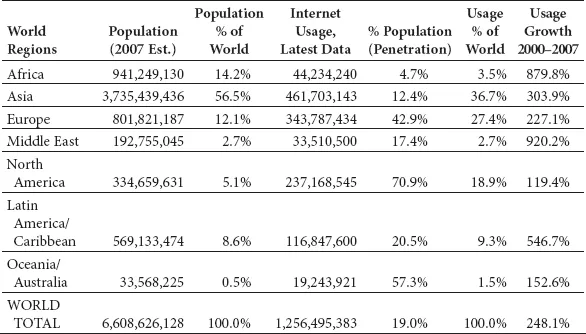

Table 1.1 World Internet Usage and Population Statistics Adapted from Internet World Stats (2007)

Consider, for example, the speed with which usage of the Internet increases. In late 2005, an important global milestone was reached—the one-billionth individual began reading, writing, viewing, and communicating online (de Argaez, 2006; Internet World Stats, 2006). Approximately one sixth of the world’s population now accesses the Internet. The growth rate has been exponential, most of it having taken place in just the past 5 years (Internet World Stats, 2006; ClickZ, 2006). If this rate continues, almost half of the world’s population will be online by 2012, and Internet access will be nearly ubiquitous sometime thereafter. You can see some of these changes in Table 1.1, which summarizes worldwide Internet usage statistics as of November 30, 2007.1

The usage statistics in Table 1.1 are far from evenly distributed by age. In countries for which reliable data are available, regardless of the number or percentage of users, Internet usage is especially widespread and regular among adolescents. In Accra, Ghana, for example, 66% of 15- to 18-year olds-attending school and 54% of 15- to 18-year-olds not attending school report having previously gone online (Borzekowski, Fobil, & Asante, 2006). In the United Kingdom, 74% of children and young people ages 9 to 19 have access to the Internet at home, and most of them (84%) are daily or weekly Internet users (Livingstone & Bober, 2005). In the United States, 87% of all students ages 12 to 17 report using the Internet, and nearly 11 million do so daily (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2005). Similar patterns are commonly found in other nations. In short, the Internet is quickly becoming this generation’s defining technology for literacy, and thus, issues of new literacies will be especially important to consider in relation to our youth.

Usage statistics are also far from evenly distributed by region and country. Schools in the European Union report 96% Internet access in 2006, with broadband access the new standard. They average nearly 70% school classroom penetration, with highs of over 90% in the Nordic countries, the Netherlands, Estonia, and Malta, and lows of 13–31% in Greece, Poland, Cyprus, and Lithuania (Korte & Hüssing, 2006). In 2005, 99% of public K to 12 schools in the United States had an Internet connection, and 93% of all K to 12 classrooms in the United States had Internet access (Parsad, Jones, & Greene, 2005). By contrast, only 5% of Mexican schools were estimated to have any kind of Web access prior to 2004 (Cavanagh, 2004), and only 26% of Brazil’s schools had Internet access, though 67% of all secondary schools had access (INEP—EDUDATABRASIL, 2005). School access is still negligible throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa.

As Table 1.1 points out, however, the fastest growth rates (from 2000 to 2006) are taking place in regions with the lowest current access rates, regions that often possess the largest populations: Africa (625%), the Middle East (479.3%), Latin America/Caribbean (370.7%), and Asia (231.2%). One can expect that the most rapid growth in the next decade will continue to take place in these regions. Even with this growth, however, it is likely that important disparities will continue to exist between and within nations. These and many other aspects of what has come to be referred generically as the digital divide (Hargittai, 2002; Hoffman & Novak, 1998) carry with them important responsibilities for local, national, and global communities committed to egalitarian ideals. We should not think that we can study new literacies as simply a technological, linguistic, cognitive, or social phenomenon in isolation from our common commitment to one another and the consequences of our work to assist with or deny full access to economic, educational, and political opportunity.

The rapid, differential rate at which access to the Internet is taking place is one aspect of the speed with which change is taking place in the technologies of literacy. It is not just that a single technology of literacy has changed with the appearance of the Internet but that the Internet, as a technology, permits immediate, global, and continuous change to literacy technologies themselves. Never before has this potential existed within a central technology for literacy. The Internet, possessing the potential to contribute to the continuous redefinition of literacy, has been a major factor in making literacy deictic (Leu, 2000; Leu, Kinzer, Coiro, & Cammack, 2004).

A global network such as the Internet makes it possible to develop and immediately disseminate a new technology of literacy to every person who chooses to access it online. We have seen the beginning of this process recently as new technologies such as blogs, wikis, massively multiplayer online games, social networking technologies, and video- and music-dissemination technologies (e.g., YouTube and Bebo) have rapidly spread by means of the Internet, each with additional, new literacy forms and functions that are reshaped by social practices. Moreover, new iterations of older technologies such as word processing software, instant message (IM) software, and others may also be disseminated with a single link. Each new version of these more mature technologies also changes the forms and functions of earlier literacies since they carry within them new potentials for literacy. Literacy is no longer a static construct from the standpoint of its defining technology for the past 500 years; it has now come to mean a rapid and continuous process of change in the ways in which we read, write, view, listen, compose, and communicate information.

Thus, literacy acquisition may be defined not by acquiring the ability to take advantage of the literacy potential inherent in any single, static, technology of literacy (e.g., traditional print technology) but rather by a larger mindset and the ability to continuously adapt to the new literacies required by the new technologies that rapidly and continuously spread on the Internet. Moreover, since there will likely be more new technologies than any single person could hope to accommodate, literacy will also include knowing how and when to make wise decisions about which technologies and which forms and functions of literacy most support one’s purposes. Finally, the notion of literacy may have to be conceived in a situationally specific fashion, since it is no longer possible for anyone to be fully literate in every technology of literacy now available on the Internet.

If literacy has become deictic, it adds a second dimension to the speed with which the technologies of literacy change on the Internet. Given the increasingly rapid appearance of continuously new technologies of literacy on the Internet, this aspect of new literacies may become more important, in the long run, than even the speed with which access to the Internet is spreading around the world. It suggests that new literacies will continuously be new, multiple, and rapidly disseminated.

Recognizing both of these dimensions, the sheer speed and the global scale of take up are of particular significance for the issues in the present volume. Both force us to confront the issue of how, why, and with what consequences new literacies are emerging as the Internet becomes an increasingly important dimension to life in the 21st century.

What Does It Mean to Be “New?”

How would we know when new literacies emerge? This issue is not as simple as it may seem at first glance. There are many challenges to understanding what it is about literacy that is now “new.” How would any individual recognize, for example, that new technologies require new social practices and new literacies? The combination of speed and scale we have discussed may mean that the changes have happened too quickly and across too broad a front for us to deeply understand what we collectively are “in.” For many, the sheer challenge of trying to keep up with changes in new technologies is all consuming. There is seemingly little or no “space” left for trying to make sense of it. This does not apply simply to the young person or the average person in the street. It is also widespread among people who are working in professional occupations, including teachers at all levels of formal education, throughout the world. For a smaller group of others who have already adapted to the literacy demands of changing technologies as a part of daily life, proficiently living each day within the cultural and literacy space that is the Internet, it may be hard to see anything “new” for just the opposite reason. How can something be seen as “new” when it is simply a facet of day-to-day existence? Yes, it may be difficult for individuals to fully recognize the existence of new literacies, even when they are using them.

Another aspect of defining newness is related to how one answers the question, “What precisely is literacy?” Any definition of literacy will determine whether some aspect of it is new or not. In the maelstrom of contemporary change, it is difficult to sort out what might be “new” in the way of literacies from what is familiar or conventional—even if one has the opportunity and motivation to reflect on the matter. From some perspectives, it might all seem quite familiar—just a matter of reading and writing on screens now, rather than on paper with pens and pencils. Indeed, if your conception of literacy is tied tightly to traditional print literacies, it may seem strange to even think about many of the things some researchers want to call new literacies as being about literacy at all. Lessig (2005), for example, talked about slices of digital animation, music, and video as the components of early 21st-century literacies: the building blocks that young people use to encode meanings (e.g., producing anime, music, or video artifacts). He argued that, for young people in first-world countries, these units of meaning making are, to a significant extent, the equivalent to what the letters of the alphabet were for their parents’ generation.

Thus, the inclination to think of literacy in terms of “new,” as distinct from conventional, traditional, and established forms, may greatly depend, for example, on whether one thinks of literacy in terms of alphabetic writing, vocabulary knowledge, and recall of information, or whether one thinks of it in wider terms such as conceiving and communicating meaning presented in multiple media and modality forms, as informational problem solving, or another broader conceptualization. Even when people do think of literacies in wider terms, there is ample scope for debate about what constitutes a phenomenon being new. Does the established simply morph into the new so seamlessly that any attempt to parcel the new is arbitrary? Or can we generate principles, concepts, and supporting evidence and arguments for making useful sense of new literacies for research purposes? These are also central issues in the study of new literacies.

Another issue in determining what is new from what is not results from the continuously changing nature of literacy. Some have questioned the usefulness of a concept such as new literacies whose referents seem to have fleeting use-by dates. This is the idea that when instant messaging appeared, e-mail became an “old” literacy. From this perspective, new literacies are seen as having a similar kind of life trajectory to motor car models: new in 2006, semi-new in 2007, and old hat by 2008.

Against this kind of perspective, many proponents of new literacies believe that new is not over on a “literacy-by-literacy basis,” such as when MOOs give way to 3-D role-playing worlds or chat palaces, or stand-alone, single-player, ascii-interface video gaming gives way to online, massively distributed, 3-D, avatar-based, multiplayer collaborative gaming incorporating real-time text chat and VoIP...