- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This second volume of Hertfordshire garden history considers how Hertfordshire's historic parks and gardens have been influenced by, and reflect, the social and economic history of their time. Beginning with the hunting parks and Renaissance gardens of the Bacons, Cecils, and Capels in the 16th and 17th centuries—and their gradual replacement by designed landscapes—this book shows how, in Hertfordshire, individuals have long sought greater space and comfort within easy reach of the capital, London. With examples from both well-known and less-visible or vanished gardens from the past 500 years, it is sure to delight garden enthusiasts.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The London connection: Gardens of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

Earth now is greene, and heaven is blew,

Lively Spring which makes all new,

Iolly Spring, doth enter;

Sweete yong sun-beames doe subdue

Angry, agèd Winter.

Blasts are milde, and seas are calme,

Every meadow flowes with balme,

The Earth weares all her riches;

Harmonious birdes sing such a psalme,

As eare and heart bewitches.

Reserve (sweet Spring) this Nymph of ours,

Eternall garlands of thy flowers,

Greene garlands never wasting;

In her shall last our State’s faire Spring,

Now and for ever flourishing,

As long as Heaven is lasting.

John Davies, Hymnes of Astraea, 15991

The reign of Elizabeth I was often symbolised as springtime, when winter was defeated and nature could flourish, as this acrostic verse in her praise illustrates. The time from her accession in the mid-sixteenth century into the first decades of the seventeenth century and James I’s reign was one of relative stability and prosperity in England, when some of the greatest gardens of the English Renaissance were created.2 There was a sense of bringing order from confusion, commonly expressed in the imagery of the time by reference to the taming and ordering of nature.3 This period saw an evolution of ideas about the natural world, from the allegorical focus of the Renaissance, when a garden was viewed as a series of emblematic representations, to the beginnings of scientific thought and experiment, as gardens became the setting for the cultivation and study of botanical specimens. The first gardening manuals were published in the mid-sixteenth century, bringing expert advice on practical horticulture and husbandry.4 With the introduction from Europe of humanist thought, drawing on classical sources, came a revival of the ideal of rural villa life and philosophical thinking about nature and cultivation, which influenced the design of gardens. The return of Inigo Jones from travels in Italy in 1615 coincided with the adoption in England of the concept of symmetry in the garden and in its relationship to the house.5 The garden became a classically influenced, structured retreat from the active world, the setting for reflection and rational discussion, masques, sports and entertainments. Gardens were designed with more direct reference to the Italian Renaissance, using symbolic designs and complex water effects.

Figure 1.1 Hertfordshire gardens of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The London connection

By the mid-seventeenth century, Hertfordshire had many of the finest gardens in England. While those shown in Figure 1.1 have long disappeared, with only the revival of part of the gardens at Hatfield reminding us of their past scale and structure, enough evidence remains for the study of some of their individual histories, the context in which they were made, and the motives of those who committed substantial resources to developing them. This chapter explores how the great early modern gardens of Hertfordshire were to a degree distinctive from those in other rural settings in England, because of the different context in which they were created. Long favoured as a convenient location for royal hunting parks and residences, Hertfordshire was now also settled by newly rich lawyers, officials and City merchants. Easily accessible, Hertfordshire was an attractive place to live, away from the crowds and disease of the city. In his 1598 survey of the county, John Norden described it as ‘much repleat with parkes, woodes and rivers’, where ‘the ayre for the most part is very salutary, and in regards thereof, many sweete and pleasant dwellings, healthful by nature and profitable by arte and industrie are planted there’.6

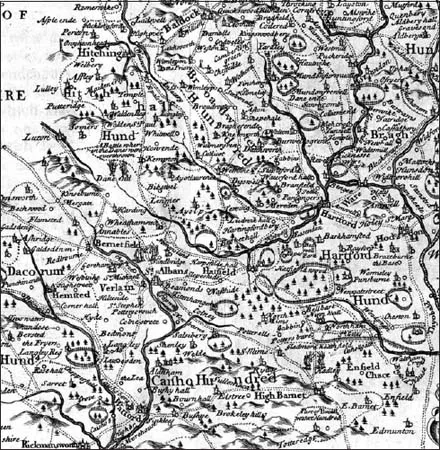

Norden added that Hertfordshire ‘is much benefited by thorow-fares to and from London Northwards’, and the inns are good: ‘no one Shire in England for the quantitie commes neere it for thorow-fare places of competent receipt’. His map of Hertfordshire (Figure 1.2) shows settlements, rivers and - unusually for maps of the time - roads, in the late sixteenth century. Direct communications between London and Hertfordshire were crucial to the county’s increasing prosperity. Four major roads linking London to the Midlands and the North crossed Hertfordshire and can be seen on the map: Watling Street (now the A5183); Akeman Street (now the A41); the Great North Road (so called by 1663, now the A1) from Islington through Barnet and Hatfield; and the Old North Road, formerly Ermine Street, the Roman military road north (now the A10), which left London at Bishopsgate and went due north via Cheshunt, crossing the Lea west of Ware and continuing north via Stamford. During Elizabeth’s reign Watling Street and Ermine Street became post roads, providing the means to exchange post within a day with the city.7 By 1637 regular coach services as well as carrier routes were in place between London and Hertfordshire destinations.8

People of wealth and influence who wanted to live outside the city, but have regular and easy access to it, took advantage of the opportunities afforded by Hertfordshire’s road system. Proximity to London and major roads north drew in individuals whose resources depended on lucrative office in the capital, rather than on rents and revenues from great landholdings. Successful mid-sixteenth-century incomers, whose Hertfordshire houses and gardens are recorded, include William Cecil (Lord Burghley) (1521-98), principal adviser to Elizabeth I, at Theobalds, and his brother-in-law Sir Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, at Gorhambury. A senior treasury official, the Queen’s Remembrancer Thomas Fanshawe (c.1533-1601), acquired and developed an estate at Ware Park. Sir Julius Caesar (15581636), an upwardly mobile lawyer who became both Master of the Rolls and Chancellor of the Exchequer, acquired land in Hertfordshire for his sons, including an estate at Benington Park. The substantial earthworks at this site have recently been identified by Hertfordshire Gardens Trust as important remains of a garden of this period.9 The Freman brothers, successful City merchants who bought an estate at Aspenden, similarly established their family as landowners with both local and national status.

Figure 1.2 Detail of John Norden’s map of Hertfordshire, 1598. From Speculum Britanniae, an Historical and Chorographical Description of Middlesex and Hartfordshire (1723 edn). 942.58/NOR. REPRODUCED BY KIND PERMISSION OF HERTFORDSHIRE ARCHIVES AND LOCAL STUDIES (HALS).

These were socially mobile individuals, whose estates with their new houses and gardens were often further developed by their equally successful sons, among them Francis Bacon at Gorhambury, Robert Cecil at both Theobalds and Hatfield, and Henry Fanshawe at Ware Park, consolidating the status and wealth of their families in Hertfordshire in the next generation. This chapter will look at some gardens which no longer survive but for which evidence is available. As Hatfield is well documented and can still be visited, it is not addressed in detail here.10 Some houses and gardens for which evidence is very limited were once places of importance. The royal residence Hunsdon House was given by Elizabeth I to her cousin Henry Carey - a soldier and statesman who worked closely with Lord Burghley - on her accession, and traces remain of the gardens of other great Elizabethan houses and gardens at Stanstead Bury and Standon Lordship. The noted gardens at Moor Park may have been made by Lucy Harrington, Countess of Bedford. The gardens at Hadham Hall, where the house was rebuilt in the 1570s by Henry Capel, another new member of the gentry, are discussed elsewhere in this volume (see Chapter 3), as is the important forest garden made by his descendant the Earl of Essex, at Cassiobury (see Chapters 5 and 7), while Chapter 2 explores Robert Cecil’s development of water gardens in Theobalds park.

The great rebuilding

The sixteenth century was a period of population rise and price inflation. In Hertfordshire, the population increased in parallel with that of London and became concentrated in the south of the county, which became the focus of stylistic innovation: the most important houses were in a band across the southeast falling within a twenty-mile radius of London (see Figure 1.1).11 The landscape and its management changed following the dissolution of the monasteries, when most monastic houses in Hertfordshire were converted to domestic use. Sixteen parks changed from monastic to private owners, and more than a quarter of the county’s land overall changed hands.12 By 1550 foundations for thirty large houses had been laid, many within old parks.13 New purchasers were building more frequently than established gentry. The influx of rising gentry and new money from London into Hertfordshire continued for centuries to come, and was central to the development of garden style in Hertfordshire.14 The London focus remained significant, to the extent that no large urban centre developed in Hertfordshire because of the dominance of London.15

At this period in Hertfordshire, estates were smaller and changed hands more frequently than in other counties. There were large numbers of comparative newcomers, and the social elite was unusually unstable: at the outbreak of the Civil War in 1641 only 10 per cent of the gentry summoned to take sides had families that were established before 1485, and 42.5 per cent had arrived since 1603.16 The ‘great rebuilding’ that took place in England during the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Plates

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 The London Connection: Gardens of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Deborah Spring

- 2 Hertfordshire’s Lost Water Gardens 1500-1750 Anne Rowe

- 3 Hadham Hall and the Capel Family Jenny Milledge

- 4 Mr Lancelot Brown and His Hertfordshire Clients Helen Leiper

- 5 Gardens and Industry: The Landscape of the Gade Valley in the Nineteenth Century Tom Williamson

- 6 Some Arts and Crafts Gardens in Hertfordshire Kate Harwood

- 7 Planting the Gardens: The Nursery Trade in Hertfordshire Elizabeth Waugh

- 8 Salads and Ornamentals: A Short History of the Lea Valley Nursery Industry Kate Banister

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hertfordshire Garden History Volume 2 by Deborah Spring in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.