1

When the Worm Forgave the Plough

Nomadic shepherds, accustomed to the age-old traditions of the Island, would find the ploughman, his queer implement and his docile beast, profoundly disturbing. But these first ploughmen . . . had come to stay and to prosper, and to sow in strange straight furrows the seeds of a new civilization.

—DONALD R. DENMAN, Origins of Ownership (1958)

Those who today make or collect or are enthralled by maps like to say that cartography is a very much older calling than agriculture. It is an assertion hugely difficult to disprove: no maps of such antiquity have ever been known to exist, even scratched on bone, or walls, or traced in preserved mud. Logic of course suggests that primitive cartography was an essential. An early hunter would have come to accept the facts of night and day, of sun and moon and stars, of the coming and passing of the seasons. And he also had to come to know, if only for his own survival, some details of his orientation—of where he was, in relation to everywhere else around him. Otherwise if he hunted, how would he find his way home? If only in his mind, he had to have a map.

In good time such a map would indeed be drawn, and once it was—even if then still in the mind and its lines not yet traced onto parchment or papyrus or scratched into sun-dried mud—it had in good time to include one purely human construct, a construct that would sooner or later lead to the idea that some early peoples would come to forge a relationship, in one form or another, to the land from which they drew their sustenance. To the idea that some people, sooner or later, would come to possess the land, to own it.

To realize this construct, consider two farmers, back in the day. Consider in particular a pair who were living close by each other in the southern part of what is now England, four thousand years ago, during what most regions of the world think of as the late Bronze Age. The time well after the Stone Age, the era before the discovery of the usefulness of iron.

These are settled people, not nomads. They may best be described as arable farmers, typical of many others around the world who at the time were working their particular pieces of land, the greater number of them growing cereals: wheat, corn, barley, millet, einkorn, bulgur, alfalfa, cotton, rice—the particular grain they sow and tend and harvest depending on where they live and work and have their being.

Since these men are in England, they are probably growing an early strain of wheat: seeds found in a cliff on an island off the south coast have recently yielded DNA samples suggesting so. Maybe elsewhere, and at the same time, similar farmers would be laboring beneath the date palms of Nile Valley, or broadcasting their seeds in the Mesopotamian wetlands between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Maybe they were scattering grains in the Great Rift Valley of eastern Africa, somewhere between Olduvai Gorge and the continent’s second river, the Limpopo. Or perhaps they were planting in the loess barrens of early China’s Yellow River, the Huang He.

Most probably the two Englishmen, if such they can be called, are known to each other, are friends. Assuredly they are neighbors, and can see one another as they work. Perhaps they are occasional rivals, mostly at harvesttime—although the concept of harvest and harvesttime was relatively new, four thousand years ago. Most societies before that time enjoyed an existence that was largely based on chasing and hunting animals and on gathering wild plants. Humans had not yet fully experimented with the idea that a man might dig into the land and in the exposed soil might plant seeds himself, and that with the passage of time and the variations of temperature and lightfall and the coming of rains might notice how the seeds he had sown changed and grew and eventually produced fruits or grains or edible leaves.

Similarly with animals: it would have taken some time before a settler might realize how best to capture and keep rather than catch and kill. He also might notice that in time, with caught animals, he might even be able to see the mechanics of breeding and the nurturing of young. He might then bend these creatures somehow to his will in a variety of ways, for giving meat or milk or becoming beasts of burden or being employed in draft.

In sum, by around four thousand years ago man would in most parts of the world have abandoned the dangers of following wild creatures across a landscape in the hope of slaughter, and of picking edible vegetation while passing through. The concept of animal husbandry was being born; the concept of settled agriculture was begun. And with this latter, so came the start of the demarcation of land. The establishment of its boundaries. And the realization of the importance of knowing how one man’s land is made identifiably separate from that of another.

The use to which a piece of land is to be put is of no consequence. It really does not matter whether the land is to be tilled, as here with these farmers, or grazed or cropped or quarried, whether it is to be built on or mined or left to lie fallow. All that is essential is that it has to be defined. Its whereabouts have to be known. Its dimensions have to be agreed. Especially its edges, where one piece of surface abuts onto another.

In other words, the piece of land has to have boundaries. It needs agreed-upon borders. It must know its place. Place may of course be many things—it may be sea or earth or a spot in the firmament or on some distant world. And place may in many cases actually be land. But land is in all cases, and always, place. Before anyone like these two farmers can lay any claim to it, so this place must be somehow distinguished from all other places. It has to be unique. It has to have position. No two tracts can occupy the same position, no two or more can be in the same place at the same time. Schrödinger might argue otherwise, but the land is not a cat, cannot truly be there and not there at the same moment. Land’s place is essentially fixed, and that fixity needs to be established and be properly and literally demarcated. It would have been these first farmers who worked out the best means of doing so.

Their ancestors—early Bronze Age men, maybe even those living in the late Stone Age, the Neolithic—would have been among the first to have broken the soil for planting. They would have done so with the use of fire-hardened digging sticks—caschroms, as students of prehistorical agriculture know them today. First a settler—settled now, no longer wishing the nomad life—would have made a single small indentation into the earth. Experimentally, wondering what might happen, he would have scattered a handful of seeds into the cavity, then smoothed the soil back over them. After this, and with time and patience and rain and sun, so came the glorious epiphany of his seeing a green shoot, a seedling, some magical entity that sprouted above the patted surface of the earth. Plant life created at his own behest! Botany, no longer merely accidental!

Later on he would extend that first small indentation—he would use his caschrom to indent the soil once more, but this time in an elongated style, which with effort he could make into what we now know as a furrow. More scatterings, more patience, more rain—and that first single seedling would in time become a straight row of plants, the bounty of just the one seed presently becoming a harvest of many. He would be able to collect the grain or the leaves or whatever part he wished, and with the bounty feed himself and those around him, maybe his animals, too. And thus was born in this one place a system of settled agriculture, and once begun it would start to accelerate rapidly.

Improvements came fast. The design of the caschrom would slowly evolve—one stick would become three lashed together with a vine, then pieces of harder and sharper materials were attached to help break more deeply into the soil—and then as the Bronze Age passed into the Iron Age, so such implements as had business with the earth itself were no longer just whittled sticks, but became tools hammered and forged from smelted metal, were made stronger and sharper and more durable. This time saw the birth of the plough and the ploughshare—among the key early components of civilization, lately regarded as standing alongside such other later seminal inventions as the stirrup, the compass, gunpowder, and, in due course, the printing press.

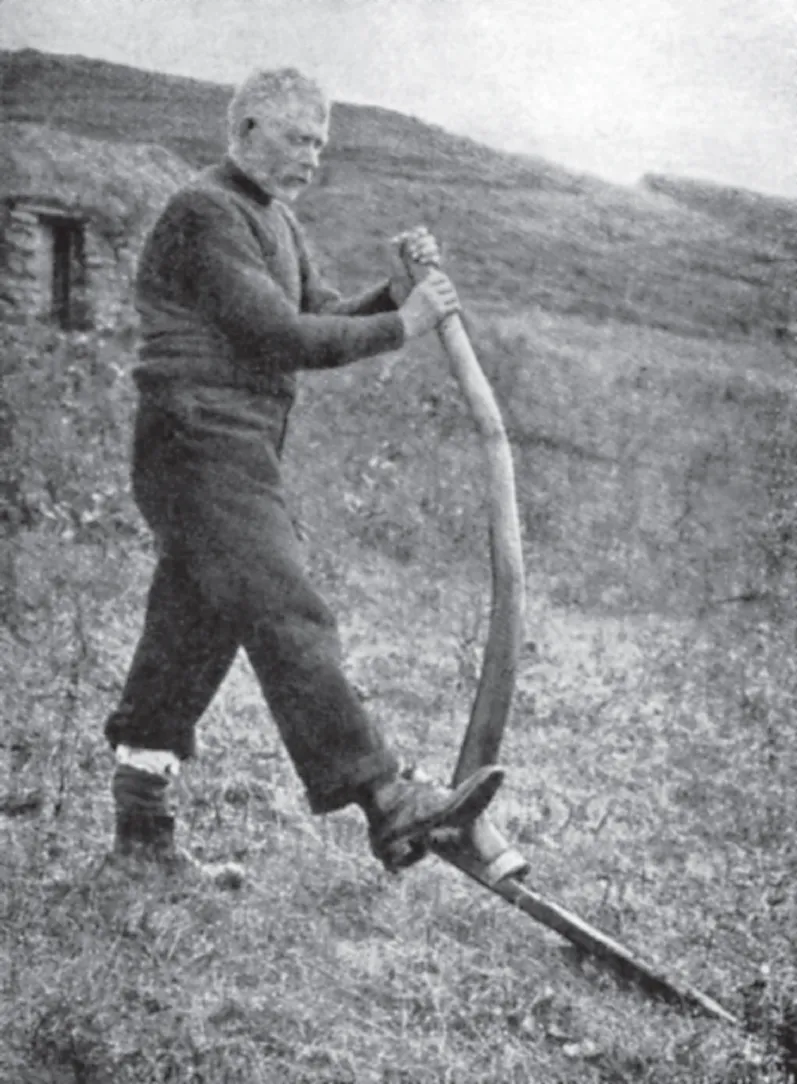

A crofter making a furrow in his Scottish smallholding using a caschrom, a sharpened-stick precursor of the plough.

The more sophisticated matters of traveling and exploring and blowing things up and disseminating news could be left for later, though. For now the simpler business related entirely to the land, then even more than today an essential and elemental feature of human existence. With some of the plough’s critical parts, the business ends, by then made of metal, so the friable and fertile earth of which the land here was made could and would be incised with deeper and straighter lines. Soon the crucial invention of the plough’s moldboard would arrive, and which would allow the soil to be turned as the plough moved through, with the turned earth duly aerated and made more productive, the resulting crops richer and taller and stronger and fuller of yield.

One further development remained—the harnessing of the captured and husbanded animals to these newly invented ploughs. Once the necessarily complex binding arrangements of leather strips and rope had been fashioned, so any number of tamed and docile but powerful four-legged creatures—oxen, mules, horses, donkeys, in some far places camels, all of them stronger and more enduring than humans—could be bent to human will in this new and previously unimagined way. The beasts could be persuaded to pull the ploughs behind them and allow their abundance of muscle to help with the digging of the furrows, and then for the planting of seeds and the harvesting of crops to be accomplished ever more extensively and effectively.

In the meadowlands of ancient southern England, the period saw the assembling of what some anthropologists have called the Deverel-Rimbury plough teams. Here in England, as in the Fertile Crescent and the Great Rift and most especially in China, where the sophistication of early agriculture predated and then outstripped all others, the business of field systems and field design begins and, with such thinking, so the true start of land demarcation.

Here, boundary lines begin. Our two farmers—for the sake of clarity, let us say a pair of these Deverel-Rimbury age farmers, of a people who were otherwise best known for their distinctive globular pottery and their burial barrows. These men tilled their lands close to a settlement in a deep valley among the rolling chalk and limestone uplands of what is now Dorset and Wiltshire. They are occupying adjoining swathes of this land. Let us imagine that one of the pair is planting his crops on river bottomland, while his colleague has located himself slightly higher on a hillside. Maybe because of the rather different terrains—or maybe because of personal whim—the two farmers decided to create furrows that run in slightly different directions.

Let us imagine as well, for sake of argument, that the man working the bottomlands arranged his furrows to run in straight lines to the north and south. Let us also suppose that his neighbor up on the hillside ran his furrows along the contour lines, that he created small terraces to keep the strips between each terrace more or less flat, so that he was not planting on earth that lay at an inconvenient angle. The relics of such strip lynchets, as these are called, are to be found in meadows across southern England today, almost hidden memorials to the ancient field systems of four thousand years ago, and fascinating and illuminating in themselves.

But in terms of demarcation, the intricacies of lynchet and furrow design are not so important. What is crucial for the origination of boundaries is the simple fact that where in this case bottomland meets hillside, where the newly ploughed furrows of the first farmer meet the strip-lynchet lines of the second, there is an obvious disconnect—what in geology would be called an unconformity. Furrow lines of the first farmer, all proceeding in a north–south direction, suddenly encounter furrow lines of the second farmer, which run in an altogether different direction—perhaps east–west, perhaps at a diagonal.

Evidence of ancient man-made earth terraces known as “strip lynchets” are still to be found in southwest England.

And this point of unconformity—which may at first be marked by a line of pebbles or stones or boulders, or by planted standing sticks, or even in due course by a crude barrier fence of wattle or a hedge of blackthorn—turns out to be a boundary. The first-ever mutually acknowledged and accepted border between two pieces of land, pieces farmed or maintained or presided over—or owned—by two different people, in this case neighbors and friends.

By the simple act of each farmer creating furrows of his own peculiar alignment—alignments either forced upon each man as a consequence of topography, or simply engineered by personal choice—so the land, for the first time, had been informally demarcated. Later on, the informal would become the settled, and then formalized. A frontier had been established. The basis of land possession had been established, and the whole complicated engine work of landownership now had been unwittingly handed its origin myth.

The two Bronze Age farmers gave birth to a system that would lead in time to the making of borders not just between individual people, but between villages, between towns, between counties and prefectures, between states, between nations. The formal fault lines of the world have their origins in the informal decisions taken by a pair of prehistoric seedsmen in Wiltshire, and by other plough teams in the Yellow River Valley, in Mesopotamia, in the pueblos of New Mexico, in the mudflats of Bengal, and in the paddies of central Japan.

THE SURFACE OF THE WORLD IS DIVIDED IN NUMBERLESS WAYS, and at a variety of scales. At the most granular and personal level is the division like this, at the level of mere fields. Such lowest-level boundaries inform the personal lives of millions, so long as they are landed to even a small degree. You are aware of such boundaries if you are a householder in a Dorset village or in a suburb of Denver or, nowadays, in Wuhan or Sarajevo or Manaus. A Bantu cowherd knows where he may graze his cattle in a kraal, and where he may not. A rice farmer in Gifu Prefecture in western Japan will show the utmost respect to the position of his neighbor’s paddy, and not stray beyond uninvited. A sheep baron in Queensland or a bison farmer in Wyoming will know the exact extent of his station. The size of each personal possession may be as varied as its function, or as the required bragging rights of its possessor: it may amount to mere fractions of an acre, or it may be measured in tens of square miles of prairie and range and take endless hours for a vehicle to cross. Each holding will however be firmly delimited by the presence of a borderline—most probably unmarked for the larger properties, though with stone walls and then wooden fences and Leylandii hedges and electric wires as the scale diminishes.

Populations of such individuals will also form clusters, will inhabit reg...