1 Carving for knaves

Juliet Fleming

In 1508, Wynkyn de Worde printed a short book ‘of kervynge and sewing’; that is, a guide to carving and serving meat, fish and other foods. Ostensibly designed to register and teach the terms and practices appropriate to the service of food to a prince, or to others of high estate, The Boke of Kervynge and Sewynge admits all the paradoxes of the courtesy manual as these are inflected in the new age of print.1 Is the information contained a true register of contemporary or newly past social practice, or was some of it coined for the occasion? Was it crafted to remind insiders of what they already knew, so that it reinforced in-group knowledge and functioned as a satisfied tallying of that information, or could it have actually taught outsiders what they needed to know to be included in the group? Could readers have used the book for the purposes for which it claims to have been written, or is the information fanciful or generic rather than profitable? Such questions are inevitably raised by the unstable address that must govern any guide to manners, but they are sharpened, and their answers require readjusting, when the guide appears in print, so that it seems to address a less localized audience than it might have done in manuscript.

But here we are considering a very early moment in the history of the English press, when a printed book is not necessarily less expensive or more popular than one in manuscript, and when the translation of information could run either way between the two media: a printer might take a manuscript book as his copy, while a scribe might be hired to transcribe a printed work. And, if, throughout the fifteenth century, manuscript books had been produced largely at the request of customers, the first English printers did not immediately depart from this model, but printed books on the recommendation of readers who might be relied on to buy or otherwise see them sold: Wynkyn de Worde numbered the King’s mother Margaret Beaufort, the cleric Richard Whitford, and the wealthy London mercer Roger Thorney among customers who commissioned and patronized his work in this way.2 But in 1500, de Worde left Westminster to set up shop in the city of London, where he began to develop a wider readership for his printed editions of religious works, school-texts, poetry, and other works. The Boke of Kervynge and Sewynge, printed in Fleet Street in 1508, was part of this initiative to broaden and service an increasing demand for English books in print.

Although no single source has been identified, the fact that de Worde gathered copy for The Boke of Kervynge from some already popular manuscript texts has long been understood. His main source was John Russell’s Boke of Nurture, a guide to service in an aristocratic household that was composed by the steward to the Duke of Gloucester some time before 1447, and survives today in three different manuscripts and an edition printed by Thomas Petit in 1545.3 Having traced the relation between the manuscripts and de Worde’s text, F. J. Furnivall, one of the founding editors of the Early English Text Society, concluded that ‘either the old printer was one of the most barefaced plagiarists that ever lived, or…the same original was before him and Russell’.4 Today, the cutting, adaptation, and repurposing of manuscript texts by the first English printers, as well as by the scribes who worked alongside them, would be described differently, using concepts of publishing and authorship more supple, and less certain, than those that were available to Furnivall. And we would conclude that even the manuscript that he speculates may be have been the source for both Russell and de Worde was most likely not an ‘original’ work, but a gathering of traditionally formulated knowledge that had been repeatedly adapted and modernized for new readers as it was copied and passed along. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly difficult for us to recall what the term ‘original’, and even the term ‘individual work’, once meant for literary historians, for isn’t it obvious that if a text is to have even a minimal degree of legibility it must be, at least in part, a remediation of words, tropes, images, genres, plots—in short, of grammatical, material, and affective forms in general—that a reader already has some chance of recognizing? It now seems safer and easier to conclude that, at least theoretically speaking, there is no such thing as an individual text. The work of the historicist literary critic will therefore often involve having to trace that adjustment of a text to its context that made it legible as an individual work within a localized historical circumstance. Such work is painstaking: it demands not only historical and literary training, but also the theoretical and bibliographical skills that become increasingly important in our discipline as we learn to ask not only what, but also where, texts are.

It is not my ambition to complete such work here. On the contrary, you could say that I do not even attempt it, for I want to describe the peculiar effect produced by the survival—intact, out of context, and almost to the present day—of the opening section of The Boke of Kervyng; that is, of a list that details 39 ‘termes of a kerver’. And here, ‘out of context’ does not mean repurposed within a new context, but indicates the peculiarly deracinated quality of a small text that has been admired and circulated among 25 generations of readers. All things exist in context, of course, but it seems worthwhile to try to develop a vocabulary that might allow us to describe the different degrees of adaptation that textual and other entities undergo in order to survive. As those experienced in translation know, some concepts are easily fitted into new linguistic contexts, where others are much more resistant to translation. This small text interests me because it was not obviously changed by the new circumstances within which it nevertheless continued to be cherished, with the result that it became stranger and stranger, even as it remained familiar, to English readers. But perhaps I should say that it began strange, for there is no evidence that, at least since the end of the fifteenth century, any of the copyists, printers and readers who reproduced and cherished the terms of carving knew what they meant.

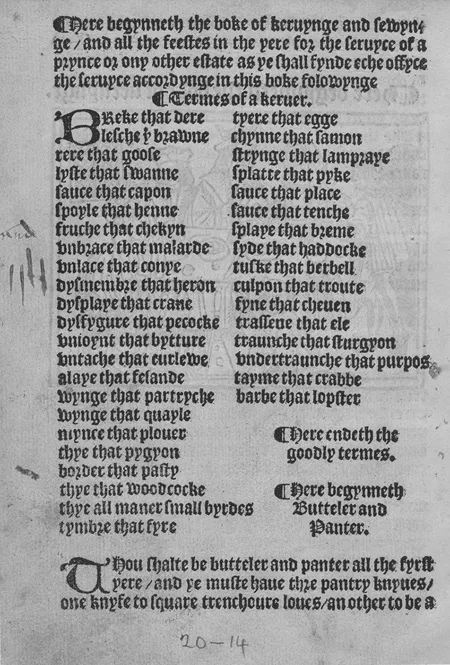

Here begynneth the boke of kervynge and sewynge / and all the feestes in the yere for the servyce of a prynce or ony other estate as ye shall fynde eche offyce the servyce accordynge in this boke folowynge (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The ‘terms of carving’, from The Boke of Kervynge (1508). Reproduced by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Termes of a kerver. |

| Breke that dere | tyere that egge |

| lesche that brawne | chynne that samon |

| rere that goose | strynge that lampraye |

| lyste that swanne | splatte that pyke |

| sauce that capon | sauce that place |

| spoyle that henne | sauce that tenche |

| fruche that chekyn | splaye that breme |

| unbrace that malarde | syde that haddocke |

| unlace that cony | tuske that berbell |

| dysmembre that heron | culpon that troute |

| dysplaye that crane | fyne that cheven |

| dysfygure that pecocke | trassene that ele |

| unjoynt that bytture | traunche that sturgyon |

| untache that curlewe | undertraunche that purpos |

| alaye that fesande | tayme that crabbe |

| wynge that partryche | barbe that lopster |

| wynge that quayle | |

| mynce that plouer | Here endeth the |

| thye that pygyon | goodly termes. |

| border that pasty | |

| thye that wodcocke | |

| thye all maner small byrdes | |

| tymbre that fyre5 | |

This list has proved remarkably enduring. It was reproduced in books of country life and cooking throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, until in William Harrison Ainsworth’s nineteenth-century historical novel, The Tower of London, A Historical Romance (1840), the pantler Peter Trusbut is described serving a wedding feast

Trusbut’s activities follow the order and retain a good proportion of the contents of de Worde’s list, while some terms omitted there are recalled in the next paragraph:

Here Ainsworth appears to be putting the terms of carving back into a practical context, as if they were describing activities once commonplace at a courtly table and in the kitchens that served it. The novel is an attempt to imagine the experience of political prisoners held in the Tower under Mary I, but the kitchen characters are there to dish up episodes of comic relief as these could be developed out of reimagined forms of Tudor customs and vocabulary. It is particularly hard to know how seriously to take these last since Sir Narcissus is a fool whose elevation at court leaves him ever uncertain whether he is being mocked or honored by his former associates when they address him in courtly terms. But if he does not know what it means to ‘disfigure’ a peacock, neither does the narrator. Ainsworth twice leaves the pantler to cope in ‘his own terms’, and carefully constructs his descriptions of serving so that a reader can’t tell whether or not he is suggesting that to ‘rere’ a swan was to bake it in a pie, to ‘display’ a crane was to roast it whole, or that a peacock is ‘disfigured’ with its own tail feathers. There is no precedent for these explanations, which actually contradict instructions offered by de Worde in a later section of The Boke of Kervynge. In making up practices to match the terms of carving, Ainsworth must have calculated that he was extremely unlikely to encounter a reader who knew any better than he did what they meant.

It seems remarkable that, under these circumstances, Ainsworth transmitted de Worde’s list substantially uncha...