![]()

Part I

Context and policy

![]()

1 Contextualizing heritage discourse in current China

Luca Zan and Bing Yu

1.1 Chinese cultural heritage: a few introductory notes

Knowing where to start a book on Chinese cultural heritage is a difficult task. There are so many things to say, so many possible approaches and perspectives, so many levels of analysis.

Perhaps the best place to start is by describing what this book is not about. It is not a book on Chinese heritage as a whole. It does not analytically or systematically reconstruct Chinese heritage, its main resources, or the change processes affecting it. Instead what matters is the intersection of these aspects – we assume the reader is somewhat familiar with them1 – and the issue of organizing, or in a very broad sense the issue of managing (or management). More particularly, we focus on dayizhi (large archaeological sites), which emerged as a policy in the period of the 11th and 12th FYP planning cycle.

Of course, to put the policy in its context, some basic explanations are needed to help the reader with a basic understanding of Chinese heritage, without delivering a systematic reconstruction. In a very selective way, this chapter provides a preliminary discussion of some important issues about Chinese cultural heritage, and their impacts in shaping the discourse on heritage and its policies. We use policy and management lenses rather than technical or humanistic views, and we focus on immovable and tangible heritage.

1.2 The Chinese heritage chain: a short reconstruction

Talking about heritage in a country as huge and old as China raises the issue of what can be realistically assumed to be known by an average reader, and what needs to be “introduced”. A fair introduction could occupy a whole book on its own, or more than one book. So here we are simply providing a few elements to better understand some of the characteristics of the Chinese cultural heritage chain and some of its distinguishing features in order to provide a context for our discussion on dayizhi.

1.2.1 A qualitative simplified introduction (for dummies)

In qualitative terms, and at an introductory level, some basic elements should be kept in mind. While we will come back to most of these issues in the following chapters, here we provide a very simple picture, a sort of introduction to Chinese immovable heritage “for dummies”, using the acronym HOME PC. Readers with knowledge of Chinese heritage can skip to the next section, where we provide some quantitative data arising from the 3rd National Investigation.

The acronym echoes the fact that the most important Western company in personal computing, IBM – one of 20 “excellent companies” identified by Peters and Waterman (1982) – has been taken over by the Chinese. This demonstrates a crucial element of the general context: the unprecedented economic development in the last three decades. The acronym is also easy to keep in mind, and it is not intimidating for the non-expert, as any “for dummies” presentation should be, while addressing the key issues in simple terms. To make things less abstract, we use an example in unpacking the acronym: the case of the most iconic site in China, the Great Wall (see CACH, 2016, pp. 669–732).

H = Huge

China is huge in terms of geographical size, and this vast extent is a constitutive element of Chinese culture and its heritage: in addition to the Great Wall, just think of heritage resources such as the Silk Road and the Grand Canal, each involving a geographical extent hard to find in other countries.2 China’s huge dimensions also have another important connotation, namely the variety of climatic conditions (with various extremes: arid and alluvial; hot and cold), which have important implications for heritage conservation and research. In addition, China is (and was) huge also in terms of population, a factor itself in the production of heritage and its variety over time, as well as in the impacts of current conditions on protection or access to heritage, with an explosion of tourism in the last 10 years.

As an example, the Great Wall has been recently calculated to be about 21,000 kilometers long, involving more than 43,000 heritage points, in a variety of latitudes and climatic conditions which easily could range from –40° to +50° Celsius or more.

O = Old

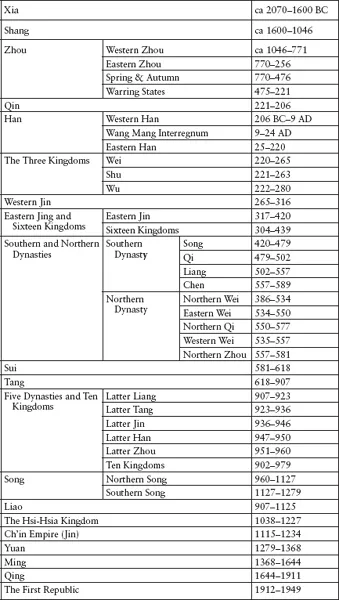

China is an old country, with thousands of years of history, which makes its heritage rich also in terms of temporal extension and articulation (from the Peking Man to the 20th century). Moreover, Chinese history is conceived and presented in a very specific dynasty-driven narrative and periodization (Figure 1.1). What most shocks the foreign scholar or visitor approaching China is the way in which Chinese history is structured along a continuum of dynasties. If it were even possible to construct such a continuum for Western civilization, one would need to find an unbroken chain from Ancient Egypt to the present day.3

Figure 1.1 The representation of the Chinese dynasties timeline

In any case, heritage resources often present individually and articulated change processes over time, a sort of conceptual if not technical multi-stratigraphy. For the Great Wall, if the best-known components are those developed or modified in the Ming and Qing Dynasties, there are still older components that date back to the 3rd century BC.

M = Material

Another recurring element of Chinese heritage is the extensive use of earthern and wooden artifacts until recent centuries. This means most heritage sites and remains are very fragile. For example, Tang Dynasty heritage, which has been compared in terms of relative meanings and quality to the European Renaissance,4 often requires archaeological excavation, which later raises difficult issues regarding the preservation of relics. For the Westerner, it would be as if Florence needed archaeological excavation, with additional challenges relating to conservation than preserving stone buildings and their frescos. Furthermore, the fragile nature of the remains often implies very difficult issues of interpretation of sites, which, even in case of important historical meanings for the scholar, are difficult to translate into narratives and eye-catching experiences for the visitor. The “wow” effect, not included in any of the UNESCO criteria but so important from the visitor’s point of view, is hard to find in many places. Most of the times the only thing you can see is some earth remains, not particularly exciting, with a few exceptions – such as the West Buddhist Temple in Beiting, where one can finally understand the greatness of such artifacts in a well-preserved context (see Chapter 9, Figure 9.4).

For the Great Wall in particular, the international collective imagination probably associates the whole asset to the brick construction, but there are many other earthen-made and hard-to-preserve parts. Even considering only the Ming period, the most recent period of construction, out of a total of 8,800 kilometers of remains, 6,200 kilometers were built by humans, of which only 4 per cent were made with brick, 54 per cent with stone, and 29 per cent with earth.

E = Economic development

In the last three decades, China has experienced an unprecedented process of economic development (Wang, 1994; World Bank, 1996; Hu et al., 2014). Among other things, this has overcome poverty conditions for 400 million people (World Bank, 2004; Zan, 2014a), and involved the construction of an incredible amount of infrastructure, within a process of urbanization that has no precedence in human history in terms of absolute numbers and rates (World Bank, 2014; Verdini et al., 2016). Overall, this has represented a unique situation of extreme threats for heritage, with the destruction of more than a few remains; but also sometimes opportunities, with rates of important discoveries linked to salvage archaeology that are themselves hard to find in any other country. Finally, a completely new potential (and threat) is linked to the development of an internal demand for Chinese culture and tourism, with numbers and a rate of increase that are impressive (see also Chan and Ma, 2004; Yu et al., 2011).

The costs of finding relevant data for our example, the Great Wall, are prohibitive, but in terms of tourism, an incomplete estimate based on the available reports refers to 17 million visitors in 2014 – which comes from data regarding just 18 out of the 90 segments open to the public.

P = Political change

The political transformation that began with the opening-up period has had huge impacts overall in the last 30 years, in what has been referred to as the “gradual revolution” (Wang, 1994; Wilson, 1996). This has brought huge amounts of money to the cultural heritage field, counter to the tendency in the rest of the world, where budgets for heritage have been cut due to budget deficit issues. On the one hand, there is a clear use of cultural heritage in terms of “cultural diplomacy” (Henderson, 2007; Winter, 2015), which is likely to have an impact on narratives and professional discourse (Sofield and Li, 1998; Chee-Beng et al., 2001; Su, 2011; Li, 2014; Yan, 2015; Zhang and Wu, 2016). On the other hand, less visible but with crucial impacts, there has been a process of institutional structuring, administrative decentralization, and framing of regulation during this period, with relevant degrees of autonomy to local governments, provinces, or lower levels (Straussman and Zhang, 2001; OECD, 2005; Pilichowski, 2005; World Bank, 2005; for a literature review see Zan and Xue, 2011; Xue and Zan, 2012). This applies also to cultural heritage, affecting practices of protection, conservation, and access to heritage (Du Cros and Lee, 2007; Guo et al., 2008; Shen and Chen, 2010; Zan and Bonini Baraldi, 2012).

The Great Wall, for example, which was added as a whole to the World Heritage List in 1987, crosses 15 provinces, 97 municipalities, and 404 counties in north China. This presents a very articulated picture, representing the institutional and administrative complexity of Chinese heritage.

C = China, Chinese-ness, Chinese civilization, culture, and cultural policy

Cultural heritage is also widely used as a tool for cultural policies aimed at supporting national cultural identity, in a context where national identity tends to develop in forms that are rarely found elsewhere. The very notion of Chinese-ness has been widely discussed in the international arena, also with reference to heritage (for example, Bagley, 1999), and in relation to two important social and political processes affecting the country in this period, which could represent a situation of double anomy, to use Durkheim’s words. On the one hand, overcoming the communist ideology, and on the other, a very specific form of de-traditionalization (Giddens, 1990), that is, the transformation of social relationships affecting urbanization of literally hundreds of millions of people.

1.2.2 Some quantitative data from the 3rd National Investigation

In a more systematic way, important elements characterizing the Chinese heritage emerge from the 3rd National Investigation carried out in 2011 by SACH (see CACH, 2016, pp. 301–303). As always in the context of national surveys (Bonini Baraldi et al., 2013), what is interesting is not only the number provided, but the very process of sense making underlying the statistics. The adoption of some specific semantic solutions – for instance, in defining categories, uses, risks, and so on – signals what is perceived as crucial in the country in ways that would differ in other countries (see Table 1.1). In this case, moreover, numbers in themselves tend to be inconsistent with current Chinese statistics, due to different levels of aggregation: they should be taken with extreme care, and are provided to give the international reader some insight.5

Overall picture

According to the Chinese law, four major categories of immovable heritage are identified in the table by their nature: ancient sites; ancient tombs; ancient architecture; and grottoes and stone steles (the 3rd National Investigation adds other info about “modern monuments and sites” and “others” that we are not taking into account). Needless to say, this reflects the specific history of China, while categories such as grottoes and tombs are much less important in other contexts, for example, in Italy, and would not be identified as such in the classification and ...