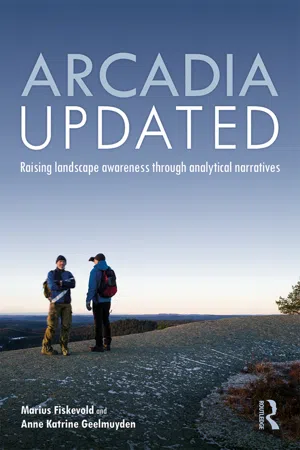

![]()

Raising landscape awareness through analytical landscape narratives

The excerpt from the poem Tonen (The Melody) by the Norwegian poet Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (Bjørnson, 1915) gives us a glimpse into humankind’s poetic engagement with the environment. This instance of pastoral art in Western culture motivates the following chapters. The pastoral tradition dates as far back as to the Idylls of the Greek poet Theocritus (ca. 305–250 bce) and plays a major role in the development of our contemporary Western concept of landscape (Hunt, 1992:50; Ruff, 2015). Hesiod’s Works and Days (ca. 700 bce) is said to have inspired Theocritus’ Idylls, which in turn served as a model for Roman poets such as Vergil and Horace. These first codifications of the coexistence between humanity and nature were revived in the Italian Renaissance and subsequently carried over into the literature, visual arts and garden design of the 16th and 17th centuries. During this period, a vast number of pastoral works were able to continuously reinvest the myth of a distant Arcadia with contemporary significance. Through reflective narration and the imaginative reinterpretation of well-known motifs shared by different religions, nations and cultures, a great variety of landscapes were created.

Over the last centuries, however, all traces of the pastoral tradition appear to have been wiped out of the human approach to cultural landscapes in planning (Cosgrove, 1998; Andrews, 1999). The once widespread cultural convention of expressing emotional attachment to nature, as well as reflecting on one’s own or one’s fellow humans’ struggles and successes, through communally understood pastoral narratives seems to have disappeared from the arena of public discourse. There may be two interrelated reasons for this. First, the reinterpretation of the myth of Arcadia has been reduced to the rendering of scenic clichés, uncritically reproduced as a sign of taste and class belonging. The reputation of the tradition itself is that it is a shallow and outdated genre (Williams, 1993; Olwig, 1996; Cosgrove, 1998). In landscape planning, the term “pastoral” has similarly been used derogatorily, denoting a superficially scenic, illusory or outdated ideal (Weller, 2006:73; Corner, 1999:156). Second, the continuation of cultural pastoralism has been disconnected from and denied its most powerful means of expression: humanity’s innate aesthetic engagement with nature has been expelled from the public arena for a long time (Geelmuyden, 1993, 1989a, 1989b).

In this situation of apparent decline, we argue that the pastoral tradition still is one of what French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard (Lyotard, 1984) has termed our culture’s “grand narratives”. Disguised as “sustainability” or, as the European Landscape Convention puts it, “a key element of individual and social well-being” (Council of Europe, 2000:Preamble), it lives on in a contemporary version. These newer manifestations of the Arcadian myth, however, differ in a crucial way from the old ones in that they fail to address explicitly visual and emotional aspects of human engagement with land. Although inherited pastoral motifs can sometimes still be found serving as implicit references in landscape analyses and evaluations, the tradition’s motivation has mostly been transformed to fit bureaucratic goals for efficient place production through a quasi-scientific methodology.

Arcadia Updated reaches back to the symbolic origins of the pastoral tradition and demonstrates how their underlying motivation can shape a critical language for analysing landscapes in a democratic planning discourse. Despite its references to land and land features, a landscape analysis moves entirely within the realm of language: in a mutual exchange and interplay between land, images and words, the entire process of landscape formation is tied to the constitutive conditions and character of its verbal utterance. In a reflective and narrative move analogous to the poem’s above, the voice of the analyst must turn the sounds of the ever-evolving world into comprehensible melodies, contemporary landscape analytical narratives (Hunt, 2000).

We argue for a hermeneutic approach rather than a positivistic one as the most appropriate for meeting the European Landscape Convention’s aim to raise landscape awareness. Every single individual sees its environment in a unique way. But instead of highlighting these differences as the problem in landscape planning (Jones, 2007; Jones et al., 2011), we have chosen to emphasise and explore the commonalities of landscape perception. This book shows that a shared landscape requires and implies a collective act of imagination. In planning, it is led by an expert and uttered through an analytical narrative. Raising landscape awareness means making visible a piece of land under a current circumstance, thus making it available for shared recognition and comprehension following the visual rationality of an analytical narrative. Through the voice of the analyst, contemporary human engagement with land can be translated into visible and potentially shared motifs that are perceivable by any attentive reader of the analytical narrative (Fiskevold, 2011).

Sustaining the poetic potential of landscapes through action

An interpretation of the poem Tonen reveals many of the complexities attached to the visual rationality of an analytical narrative. We interpret the poem as a form of analytical narrative, and we shall emphasise its calling for subjective imagination, traditional pastoral motivation and contemporary activation.

Imagination, motivation and activation make landscapes visible

First, the poem invites its readers to imagine an episode that could potentially take place in anyone’s life. As the words meet the eyes of the reader, they support the realisation of an image perceived by the reading subject, however invisible for others. In order to be known to others and to become an object of discursive exchange, the image has to acquire a position in an intersubjective world. The materialisation of the image follows articulated motifs, such as the woods, the flute or the boy’s wandering. These motifs in no way appear out of thin air or float in a void, even though they could be assembled out of all kinds of material things. Motifs are closely attached to a horizon of motion, reflecting the boy’s roaming in the woods, and a horizon of comprehension, reflecting the boy’s gradual acquisition of insight about his passionate experiences. From a wide range of opportunities, both the landscape image of the poet and the poem’s objective motifs are attached to a piece of land and connected to an attitude to nature which has found expression in the pastoral tradition in Western culture. The act of imagination provided for by the analytical narrative is the essential aspect of a visual rationality, and is the foundation we must rely on when our goal is to raise landscape awareness. Imagination ties an individual’s invisible image to visible motifs that are drawn from within the frames of shared horizons of motion and comprehension.

Second, the poem invites its readers to trace the image back to its pastoral sources. As the words meet the eyes of the reader, the image of a boy roaming in the woods emerges into appearance. With Ken Hiltner (Hiltner, 2011) we shall trace how landscapes emerge into appearance and why this appearance is not a matter of a day’s habitual course, but emerges as a rare event. The boy is troubled by his longing for the melody he once perceived in the woods. He thereby enters a liminal state of mind, here expressed as the motivation to stop the flux of nature by making it into a replicable object of possession. With the art historian Erwin Panofsky (Panofsky, 1982) we shall trace pastoral landscapes’ display of a discrepancy between opposite life forces that govern the human condition at any time. In the end, the boy’s struggles with his passion to master the melody’s presence open his eyes and his thoughts to an emancipating insight. With the literary scholar Paul Alpers (Alpers, 1996) we shall trace the pastoral way of dealing with life as the individual’s reflection on his or her “strength relative to the world”, and as a potentially emancipatory attitude. All these instances of motivation, emergence into appearance, discrepancy and emancipation sustain the reflective process in which landscape as sight is intrinsically bound to its meaning and evaluation, an insight.

Finally, the poem invites its readers to activate and actualise the image, referring it to what they are presently doing in their contemporary, everyday life. As the words meet the eyes of the reader, they symbolically depict the area as the world in which humanity moves, the things humanity fabricates, and lastly the stance humanity takes in relation to nature’s variety and change. Arendt has described these practices as labour, work and action. These practices are the fundamental conditions “under which life on earth has been given to man” (Arendt, 1998:7). As the boy unconsciously goes about his daily life (labour), roaming in the woods, the surroundings attract his attention in a way that is poetically visualised in the form of a wonderful but, alas, illusive melody. Once aware of it, he starts longing to relive his wonderful dream, and he sets about carving a flute (work) with which to bring the tune to life again and ensure its lasting presence. But the flute, he realises, cannot make it reappear as he first heard it. In the poetic shape of the voice of the Master (action), he admits that his work is a manifestation of human hubris and reconciles himself with that insight.

Landscapes as statements and ideas

The final voice, an action on the part of the poet, is a statement. It represents the insight that the tune will forever remain one of nature’s secrets, one that humanity might sometimes come close to taking part in but will never be able to capture entirely. In Arendt’s terminology, action holds a special position. It is the oral communication between individuals, the way in which the individual, through his or her utterances, takes a stand in the world and declares his or her singularly outstanding capacities. It is the zoon politicon’s characteristic way of expressing its unique potential as an individual of the human species: through articulating a response to its present environment. Through speech, the analyst constructs a temporary image of the world that is independent of direct involvement with the “‘artificial’ world of things” (work) or “the biological process of the human body”: “Action, the only activity that goes on directly between men without the intermediary of things or matter, corresponds to the human condition of plurality, to the fact that men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world” (Arendt, 1998:7).

Only in the action of the analyst can the different landscape shareholders that are gathered in dialogic imagination, pastoral motivation and current actualisation be linked. It is the action of the analyst, the articulation of a landscape, which foregrounds some images in favour of others and assembles them into visible material motifs of a currently relevant landscape. The action of the analyst, the Master’s voice, links sensations to meaning within the frames of a lasting narrative. Any landscape analysed by an analyst is similarly reconfigured through the language and speech of the analyst. As we credit the poet for a poem, we should credit the landscape analyst for the landscape of the analysis.Both the motivation to make land visible as landscape and the activation of images related to contemporary practices ensue from the performance of a landscape idea symbolising a humanity-nature relationship.

An idea always guides the whole composition of an analytical narrative. Originally, “an idea or eidos is the shape or blueprint the craftsman must have in front of his mind’s eye before he begins his work” (Arendt, 1978:104) Still linked to humanity as toolmaker (in the activity of work), the idea was a material template, which the craftsperson used as his or her id...