![]()

1The path of contemporary Japanese politics

Four stages of development

The evolution of Japanese politics from the end of the Asia Pacific wars to the present can be divided into four stages. This chapter aims to highlight the distinguishing features of each stage along the postwar path. The first phase, “high politics,” between 1945 and 1960, is characterized by ideological confrontation between progressives and conservatives. The second phase, “interest-centered politics,” spanned the years 1960 to 1980 and centered on profit acquisition. This was followed by a third phase of “life-centered politics,” which sought ways to resolve various issues spurred by the material-centered thinking of the previous stage. This stage commenced from around 1980, as Japan entered the post-industrial age, and continues to this day in tandem with the fourth stage, what may be called “globalization politics,” from the mid-1990s, as the effects of globalization became more pronounced (Berger 1979; Shinohara 1982, 1985).

From defeat in war to reconstruction: the era of high politics

Japan’s defeat in the Asia Pacific wars on August 15, 1945 and the reforms introduced during the postwar US Occupation mark the beginning of contemporary Japanese politics. The postwar reforms dismantled the Meiji state system, and particularly targeted the forces and structures that gave form to militarism. However, Occupation policy permitted the retention of a number of agencies, including important elements of the bureaucracy and the emperor system. These reforms culminated in the 1947 Japanese Constitution. After Japanese sovereignty was restored in 1952, “conservative” forces that favored revising the postwar constitution battled “progressive” forces determined to protect it. The document remains controversial first because it was drafted by the occupying American forces, and second because it prevented Japan from maintaining a military or engaging in war.

The structure of international society during the Cold War also impacted Japan’s domestic politics and further aggravated the antagonism between progressive and conservative forces. These forces agreed to merge in 1955 to form a “two-party” structure consisting of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the Japan Socialist Party (JSP). What became known as the “1955 System” centered on the antagonism maintained between conservatives and progressives. The system was established at a time when the Japanese economy was advancing from postwar recovery to high-speed economic growth. It was also the same year that organized labor inaugurated its annual “spring wage offensive.” The Japanese postwar Constitution, which defined the emperor as the symbol of the state, deriving his position from the will of the people, also took root among the citizenry during this initial stage.

Revolutionary postwar Japan

The Constitution laid the foundation of revolutionary change in Cold War Japan and chartered the course of contemporary Japanese politics. Defeat brought about the collapse of two pillars of the prewar system, the traditional emperor system and the military faction, as Japan came under the authority of an Allied Occupation that stressed “demilitarization and democratization.” The United States initially aimed to prevent the reemergence of the militarist state that had emerged in Japan, while Japan’s Asian neighbors that had suffered under Japanese invasion and occupation also feared a revival of Japanese militarism. These circumstances led to the promulgation of a postwar Constitution in May 1947. Its controversial Article 9 renounced Japan’s right to maintain a standing army or engage in war. The article’s most avid supporters were the Japanese people themselves, many of whom had lost relatives and friends during the war, and suffered from starvation and shortages of food, clothing, and shelter both during and after the war.

The Cold War’s origins predate the conclusion of World War II with a rivalry over territorial influence developing between the United States and the Soviet Union as they cooperated to determine postwar issues. Japan’s fate was sealed with the war’s end and its subjugation under US occupational rule. Japan would be pulled into the Western camp and its diplomatic and security policies would be subjected to overwhelming American influence. With the intensification of the Cold War, and Japan’s lagging recovery, the United States in 1948 “reversed” its Occupation policies to secure its new partner as a staunch ally in the East Asian region. Economic recovery took priority even over democratization, and US voices advocating Japanese remilitarization began to gain force. The United States made its technology and markets available to Japan, and negotiated its former enemy’s access to Southeast Asian markets under its influence to precipitate Japan’s quick economic recovery. A combination of American aid and timely orders for “special procurements” during the Korean War (1950–1953) allowed the Japanese economy to recover to its prewar level and facilitated future growth. This approach divided Japanese between those in support of a new approach that potentially could draw Japan to the battlefield, and those supporting the pacifism symbolized by the peace declaration—Article 9 of Japan’s postwar Constitution.

The policies of Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru and his cabinet, which supported US policy and brought economic growth to Japan, are still held in high regard in certain quarters today. But Japan’s inability to extricate itself from a slavish adherence to the United States in terms of diplomacy and security has cost Japan dearly over the postwar decades (Dower 2010: 181). Okinawa provides a stark example of these costs. The United States occupied these islands after the war as an Occupation administration separate from that of Japan, thus severing Okinawa from the Japanese archipelago. Even after Japan regained sovereignty over Okinawa in 1972, this prefecture continued to bear a heavier burden than other prefectures in hosting the majority (about 75 percent) of US military bases in Japan (Ōtake 1992). Moreover, the economic stability quickly realized by Japan in the postwar period caused many to forget, or ignore, the heavy burden that the security pact has placed upon the Okinawan people’s shoulders. Okinawa has thus become known in certain circles as a “domestic colony” of the US military (Sakamoto 1997). This postwar legacy, that continues to this day, has thus promoted questions regarding the legitimacy of Japanese democracy.

The changes that the Japanese main islands experienced under the aegis of the US Occupation were so extensive that some have dubbed this period Japan’s “second opening,” the first being the efforts led by Matthew Perry in 1853–1854 that forced upon Japan the “unequal” Treaty of Kanagawa. Resting on the twin pillars of antimilitarism and democratization, the US administrative policy disbanded military organizations, but also ultra right-wing organizations, the zaibatsu (industrial conglomerates), and a traditional system of land ownership that had supported Japanese militarism. The intention behind the dissolution of the zaibatsu was to separate ownership from management and prompt the rise of a new generation of managers. However, this aim ended prematurely. As the economy recovered, the zaibatsu were able to reconstitute themselves as keiretsu (enterprise groups) that centered on banks that provided investment funding.

The new land system introduced by the United States increased the number of independent farmers while diminishing the influence of the prewar local elites who constituted the landlord class at the time of the war’s end. In their place, the influence of former tenant farmers, who had played important roles in dissolving the old land ownership practices and establishing new agriculture cooperatives, increased at the local level. This new group of “managerial elites” replaced the prewar elites (Masumi 1983: 313). The agricultural cooperatives that emerged relied on these farmers developing strong ties with the political world through connections primarily with the LDP; they soon became among the party’s most influential supporters.

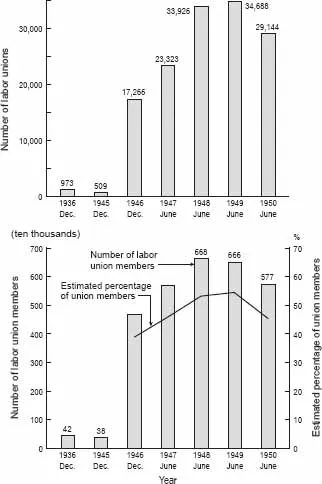

In tandem with democratization, purges drove out supporters of the wartime and militarist systems. By 1948 approximately 200,000 Japanese had been removed from official positions, causing a political power shift at the local level (Masumi 1983: 167–176). In addition, the Occupation forces granted widespread recognition to the political activities of labor, leading to a rapid increase in labor unions (Figure 1.1). These unions threw their support behind the progressive parties JSP and Japan Communist Party [JCP]), giving a strong boost to these “progressive” (kakushin) political elements. The entire legal system was also democratized, as were the educational and cultural fronts. These institutions were modeled after their American counterparts. The series of early postwar reforms was ultimately codified in the Japanese Constitution promulgated in May 1947.

Figure 1.1Student labor union increases.

Source: Masamura 1988: 35.

Notes

The figures for 1945–1946 do not include members of the All Japan Seaman Union (Zen Nihon Kaiin Kumiai). The estimated union membership percentage was derived by calculating the ratio of laborers to labor union membership. Prewar statistics were from investigations by the Homusho; postwar from the Koseisho.

The reforms introduced by the postwar Occupation forces were quite comprehensive. However, some observers also see continuities that tie the prewar and postwar eras. According to Chalmers Johnson, in the late 1920s, Japanese anticipation of an eventual war by European states and the United States led them to institute “industrial rationalization policies” and “industrial structure policies.” These politics persisted in the postwar period and served as special features of Japan’s postwar high-economic-growth era. This growth was characterized by strong bureaucratic and industrial ties, and by enterprise unions that contrasted greatly with the independent trade unions of the Western states (Johnson 1982, chapter 3).

The US Occupation administration permitted the emperor, who stood at the center of the prewar political system, to have a central (albeit “nonpolitical”) importance in the postwar period. Likewise, the preservation of the prewar bureaucratic system allowed the bureaucracy to assume an indirect role in the postwar governance of Japan. With the exception of the Home Ministry, whose wartime role could not be denied, the prewar bureaucracy survived nearly intact, and continued to play a central role in postwar politics.

The structure of the 1955 System

The trends exhibited by the Occupation forces encouraged conservative politicians in the early postwar period to organize into two rival parties—the Liberals and the Democrats—while progressive politicians coalesced around the Socialist and Communist parties. The strength of these political parties was heavily influenced by the Cold War that dominated the international environment, which gave rise to a polarizing structure that has been dubbed the “domestic Cold War.” The progressive forces, led by the two political parties and organized labor, championed socialist policies and faced off against conservative forces. Alternatively the Liberal and Democratic parties pursued polices that were anti-Communist and favored rearmament as part of a broader revival of the prewar structure. Many Japanese, still harboring vivid memories of their wartime experiences, threw their support behind progressive party politics.

Proponents of progressive politics longed for a “rational” and “modern” form of politics and society that would sweep away the irrationality that characterized the prewar and wartime emperor-centered military state. They aimed to achieve a “richer” lifestyle as an escape from the prewar and wartime deprivation they had experienced. However, progressives, led by the left-wing JSP, misconstrued popular sympathy for their politics to mean a general support for their particular brand of socialist ideology. The party thus made little effort to fully comprehend the sentiments of its supporters. Consequently, support for the party gradually faded as economic recovery and high-speed economic growth delivered relative recovery (Takabatake 1979).

The government of Prime Minister Hatoyama Ichirō in 1954 championed a platform aimed at revising the Constitution to that which existed under the prewar system. This triggered resistance from the progressive forces. Determined to secure at least one-third of the seats in the Lower House of the Diet (the parliament) as a bulwark against constitutional revision, the progressive parties backed both the left-leaning and right-leaning socialist parties—which had traditionally differed on issues regarding the peace treaty between Japan and the Allied forces—and called for the two to reunite. On the opposite side of the political coin a business community that viewed the growth and possible merger of the two socialist parties with growing alarm urged the conservative Liberal and the Democrat parties to merge to counter the socialist threat. Thus, in 1955 the two conservative parties answered the challenge of the merged socialist parties by forming the LDP. The goals of this enhanced conservative base were reflected in the following manifesto:

Looking at the current conditions in the country, the spirit of patriotism, self-reliance, and independence has been lost. Political confusion reigns, the economy cannot stand on its own, anxiety over the people’s livelihood persists, and class conflict in pursuit of despotism rages on. This result is due, in part, to our defeat in the war and to mistaken policies enacted during the early part of the Occupation. While democracy and freedom, which were championed by the Occupation as the guiding doctrines for a new Japan, should be respected and upheld, the direction of its early policies weakened our country. Reforms to the Constitution, education and various other institutions unfairly suppressed our sense of nationhood and patriotism, while the authority of the state became fragmented and weak. In the meantime, such changes that arose in the international situation, as communism and the forces of class-based socialism took advantage of the situation to precipitate their rapid rise.

At the core of our party’s doctrine are liberty, human rights, democracy and the defense of parliamentary politics; unyielding opposition to the despotic forces of communism and class-based socialism; the pursuit of progress with consistent regard for order and tradition; the establishment of government that is reflexive, just and responsible; increased national prosperity and citizen welfare, while contributing abroad to Asia’s prosperity and to world peace; and being a moral party of the people that earns the trust of the nation.

(Tsuji 1966: 124)

Many Japanese who imagined British parliamentary politics as the ideal political situation welcomed the advent of “two-party politics.” In reality, however, unlike the LDP even the newly united JSP never gained more than half the number of parliamentary seats. At this time, the JCP also turned from revolutionary, violence-centered political activities to favor a policy of effectuating socialism through the process of parliamentary politics, and parliamentary dem...