![]()

1Introduction

Limited government

A century of spending

The facts speak for themselves. In 1830, the United Kingdom spent 10 percent of its GDP on public outlays.1 The country had a GDP that was a little over 0.4 billion pounds. Industrial capitalism rapidly expanded the size of the country’s wealth. By 1860 Britain’s GDP had risen to 0.7 billion pounds. In the meantime, government spending had fallen to 9 percent of GDP. By 1890 GDP was 1.4 billion pounds and spending a still-modest 10 percent. Yet after the 1890s, something changed. In the first 15 years of the twentieth century, public outlays rose to an average of 15 percent of GDP. From that period onwards, public expenditure kept climbing.

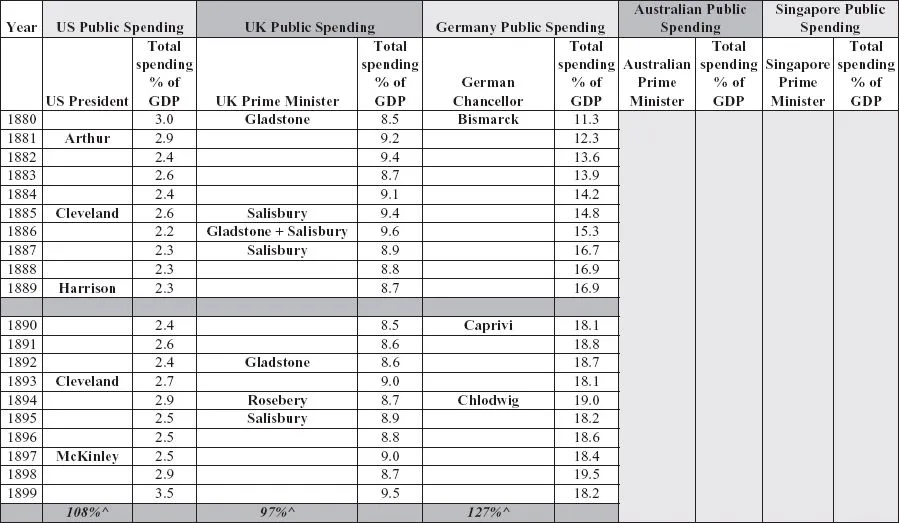

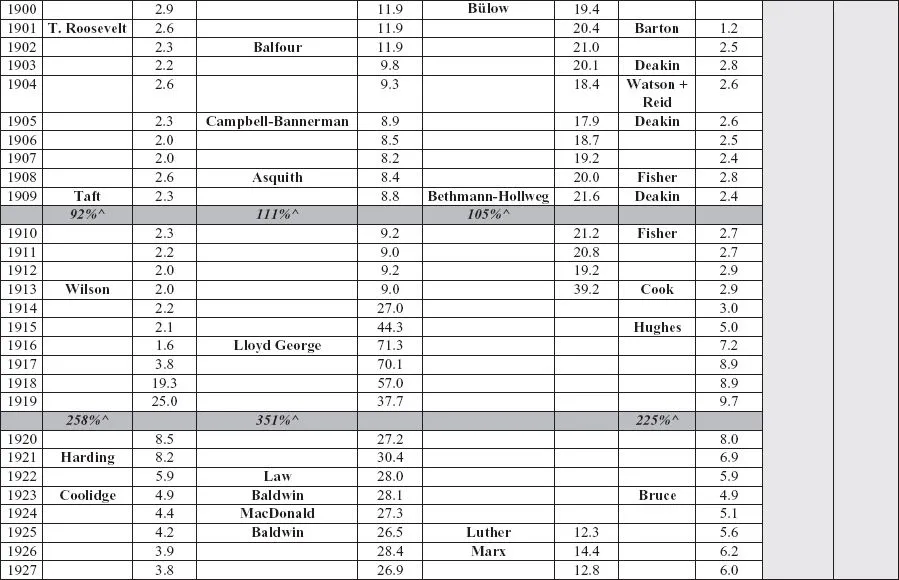

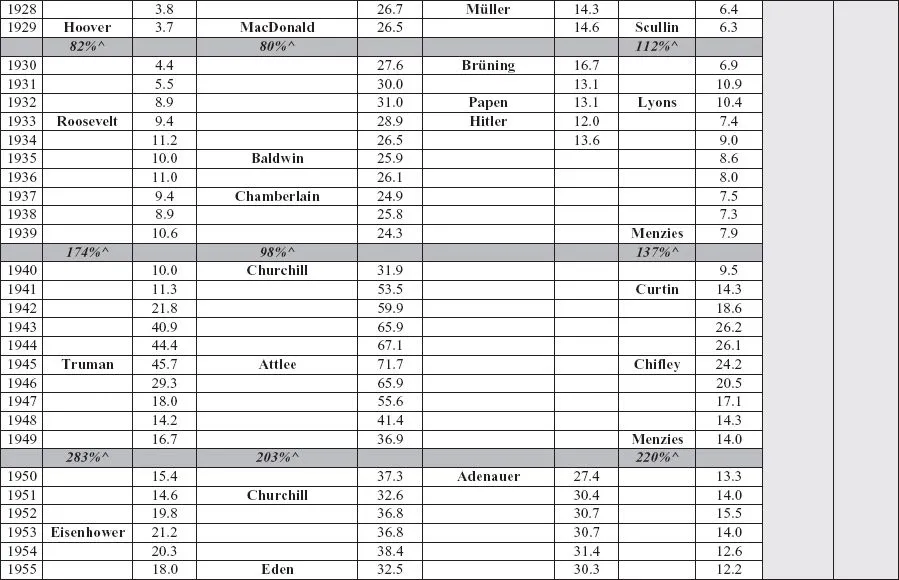

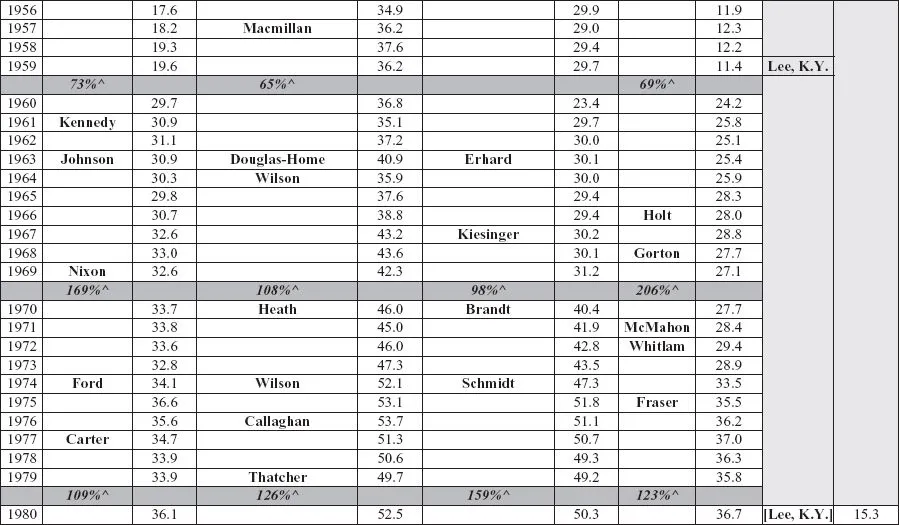

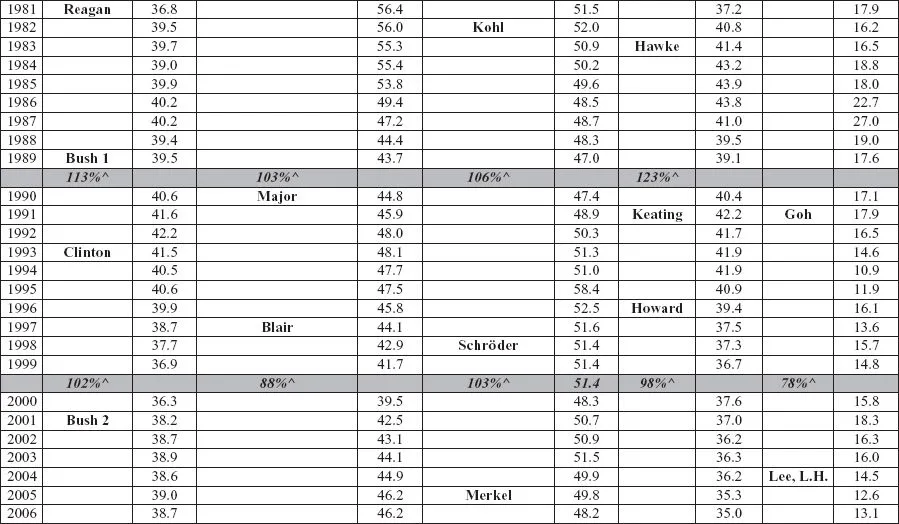

The biggest leaps in twentieth-century public spending were connected to the First and Second World Wars (Table 1.1). Public expenditures invariably spike during wars. But in the twentieth century, having risen they did not return to pre-war levels once hostilities were over. This broke with previous experience. In the past, mass conflicts like Europe’s deadly Thirty Years War (1616–1648) did not lead to a permanent increase in the size of the government. So something else aside from the effects of war was at play as the twentieth century unfolded. The fiscal consequences of the great wars of the century were folded into a larger and historically distinctive structural dynamic. The public sector in the major international economies expanded dramatically and persistently (Table 1.1). Britain spent 27 percent of its GDP on public outlays in the 1920s and 1930s. Then 36 percent in the 1950s, 39 percent in the 1960s, 49 percent in the 1970s and 51 percent in the 1980s. It declined in the late 1980s to 46 percent. This paved the way for the longer-term average of 46 percent through the 1990s and 2000s. From 2010 to 2017 this dipped slightly to an average of 44 percent. The trajectory across the decade was downward. Elsewhere, in other major economies, public spending grew from an average of 22.8 percent of GDP in 1937 to 27.9 percent in 1960 to 43.1 percent in 1980.2

Table 1.1 Public sector spending

^percentage increase over the previous decade.

Sources: IMF, Historical Public Finance Dataset 1800–2011, government expenditure as % of GDP plus government interest payments on debt as % of GDP (cf. ourworldindata.org/public-spending for calculation methodology); US and UK 2012–2016, ukpublicspending.co.uk, usgovernmentspending.com; Australia 2012–2015, Singapore 1980–2015, Germany 2012–2015, IMF Government Finance Statistics Yearbook 2016; Singapore 2016–2017, UK 2017, US 2017, Australia 2016–2017, Germany 2016–2017, IMF Fiscal Monitor.

The growth of the state was not uniform across the board. Some segments ballooned. Over the long run, other parts hardly grew at all. We see this if we compare the cases of defense, welfare, pensions, health and education spending along with the remainder (general expenditure). In 1900, public spending on these in the UK consumed 3.87, 0.57, 0, 0.3, 1.36 and 8.05 percent of GDP respectively. In 2016, spending on the same devoured 2.39, 6.02, 8.25, 7.40, 4.48 and 12.1 percent of GDP.3 Across the century, defense spending declined while general expenditure increased quite modestly. In contrast, the share of GDP spent on welfare, pensions, health and education expanded radically: 10-fold, 80-fold, 24-fold and 3-fold respectively. The classic core of the state—as it had been constituted in the nineteenth century—was smaller at the beginning of the twenty-first century than at the start of the twentieth century. Amongst other things mechanization had made armies less expensive. Meanwhile the income-support and healthcare functions that the state acquired early in the twentieth century grew to such an extent that they dwarfed the old classic core.

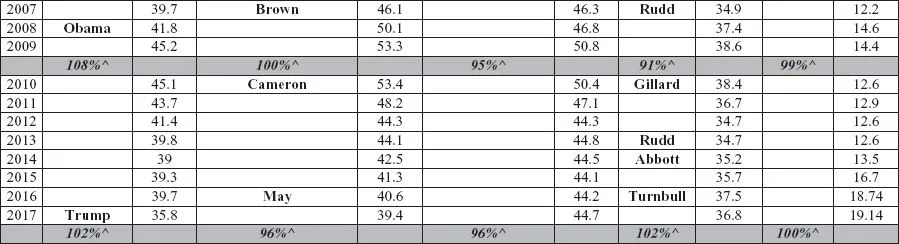

The growth of state spending and public employment had a dampening effect on economies. Industrialism—in combination with modern capitalism, large-scale urbanism and the public sphere—had a catapulting effect on modern economies after the 1770s. What resulted was a massive and historically unprecedented expansion of wealth driven by increases in productivity. The fruits of this wealth were broadly distributed to populations through rising real levels of household income. A great upward spiral occurred. Increased affluence drove greater wealth that sought higher productivity that produced added real wealth that resulted in more prosperity that was reflected in greater purchasing power. But the pace of this beneficial upward spiral was slowed by one thing. Beyond a certain virtuous level, public spending inhibits economic activity (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 US state and economy, averaged indicators for specified time periods

Sources: IMF, Historical Public Finance Dataset 1800–2011; Rose, Table 7.3; Belman, Gunderson, Hyatt, Table 2; Anderson, Table 2.6; US 2012 Census of Governments: Employment; US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment, Hours, and Earnings, 2012; Tucker, Table 1; Gordon, 2010, Table 4; OECD multifactor productivity, annual growth rate (%), 1985–2016; OECD, Public administration, defence, education, health, social work, % of value added, 1970–2016; Economic Report of the President, series 1950–2016.

Good public spending is a function of necessity. Most human needs can be satisfied by multiple providers. But a limited number of needs are best suited to one provider. Private armies bring chaos, not order. Likewise private police forces. Neither are very efficient. Similarly, it would cause bedlam if a plaintiff and a defendant in a court of law could rest their cases on different systems of law. Nor does it make sense for me to build my own highway or try to control the spread of infectious diseases. As a matter of practicality, some things in life are best suited to a monopoly provider, namely the state. The state can directly provide these or else can license a private operator to do so. But even if the latter proves more efficient, there is still only one underlying payer. A private-toll, i.e. privately taxed, highway may well avoid cost-inflating construction feather-bedding. Even so, the state remains the ultimate owner of the highway.

But with the benefits of the state also come costs. Beyond a limited range of functions, the costs begin to outweigh the benefits. Why is this so? First, every dollar that the state raises has a cost.4 Taxation has to be complied with, administered and enforced. This is an expensive way of raising revenue. Much more so than savings and investments. Second, the primary media of the state—instructions and rules—are time consuming compared with the media of promises and patterns that are widely used in markets and industries. Laws that are based on general principles are efficient. But the micro-rules of government regulation are not. Overall, government spending is significantly more wasteful than private spending. The problem is not so much that public sector employment is ‘unproductive’ as Adam Smith (1723–1790) put it.5 Rather its productivity is low (Tables 9.1, 9.2, 9.3, 9.4 and 9.5). By applying machinery to production, industrial capitalism unlocked the secret of productivity. But public-sector organizations routinely resist the logic of industrial society. Consequently, the larger public-sector employment is, the greater the drag on a nation’s economic productivity. This affects its wealth, prosperity and general well-being.

From natural rights to purposive organizations

Through the nineteenth century an invisible ceiling applied to public expenditure, at around 10 percent or less of GDP. There were exceptions, like Bismarck’s Germany (Table 1.1). But the exceptions proved the rule. Ten percent of GDP was the natural limit of limited government. It meant, in effect, a ‘night watchman’ state devoted to defense, law, order and essential public infrastructure. It had the same means of acting as any state has. It could compel behavior by law or force. What made it different was that it mobilized such means in the service of a clearly defined set of purposes. The function of the minimal state was to protect persons, property and promises and, where necessary, provide public works when private works did not suffice. Whether the state acted by means of law or force, it did so in principle for a limited range of purposes. But where did such purposes come from? Ultimately, they are rooted in the doctrine of modern natural rights formulated by the seventeenth-century English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704).

Locke’s key proposition was plain and simple. The state existed to protect an individual’s ‘life, liberty, and estate’.6 In a more expansive formulation of this he proposed that state power was properly limited to the preservation of the ‘civil interest’ of an individual. This was a person’s ‘life, liberty, health, and indolency of body; and the possession of outward things such as money, lands, houses, furniture, and the like’.7 Indolency referred to the absence of pain. The American Declaration of Independence (1776) restated Locke’s sentiments in hard-boiled prose: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’

Like all general principles, the idea of the natural rights of the individual was subject to interpretation. In some twentieth-century interpretations the right to life was transformed into a ‘right to health care’. In other interpretations ‘life’ suggested a moral duty of the state to outlaw abortions. In still other interpretations ‘life’ was translated into a ‘right to a minimum living income’. In the nineteenth century, the idea of property was subtly refigured to include skills and talents. What followed from that was the assertion that individuals had a natural ‘right to an education’. Education provided by the state was deemed necessary to develop the gifts of every person into express and useful talents. In such ways, the doctrine of natural rights evolved into a doctrine of social entitlements and human rights. Classic liberalism turned into social liberalism. What accompanied this was the evolution of the small state into big government.

Locke...