eBook - ePub

The Making of the Creeds

Young

This is a test

Share book

- 130 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Making of the Creeds

Young

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In lucid and non-technical prose, Young demonstrates how and why the two most familiar Christian creeds - the Apostles' Creed and the Nicene Creed - came into being. She aims to bring the creeds back to life again in the challenging and demanding contexts of contemporary life.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Making of the Creeds an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Making of the Creeds by Young in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christianity1

The Making of the Creeds

Christianity is the only major religion to set such store by creeds and doctrines. Other religions have scriptures, others have their characteristic ways of worship, others have their own peculiar ethics and lifestyle; other religions also have philosophical, intellectual or mystical forms as well as more popular manifestations. But except in response to Christianity, they have not developed creeds, statements of standard belief to which the orthodox are supposed to adhere. Other religions have hymns and prayers, they have festivals, they have popular myths, stories of saints and heroes, they have art forms, and have moulded whole societies and cultures. But they have no ‘orthodoxy’, a sense of right belief which is doctrinally sound and from which deviation means heresy. In practice, Christianity has all the characteristics mentioned in common with other religions, and like other religions it has taken many different forms and developed many different lifestyles over the centuries as it has been incarnated in different cultures; but in theory Christianity is homogeneous and its homogeneity lies in orthodox belief. Despite the ecumenical movement, Christian groups still claim that their truth is the truth, betraying that this is something they all have in common: namely, a distinction between true belief and false belief. There may in practice be a number of different orthodoxies, but ‘orthodoxy’ seems characteristic of Christianity.

Now when you stop to think about this, it really is rather surprising. Christianity arose within Judaism: as has so often been said, Judaism is not an orthodoxy, but an orthopraxy – its common core is ‘right action’ rather than ‘right belief ‘ – Judaism was not the source of Christianity’s emphasis on orthodoxy, and has formulated its ‘beliefs’ only in reaction to Christianity. Nor can we find the source in the teaching or attitudes of the founder of this religion: a dispassionate look at the gospel records hardly suggests a figure with episcopal authority propounding dogma and excluding debaters or doubters. So where, then, did this feature of Christianity come from? The purpose of this introductory book is to try and trace how and why Christianity became a credal religion, and how and why doctrine developed as it did. We begin with the creeds themselves: what was the origin and function of the confessions of faith we still find in Christian liturgies – the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed?

There is a legend already developed before the fifth century that prior to setting out to preach the gospel all over the world, the apostles ‘first settled an agreed norm for their future preaching so that they might not find themselves, widely separated as they would be, giving out different doctrines to the people they invited to believe in Christ. So they met together in one spot, and, being filled with the Holy Spirit, compiled this brief token, as I have said, of their future preaching, each making the contribution he thought fit; and they decreed that it should be handed out as standard teaching to believers.’2 Not much later we find the various clauses each attributed to a named individual apostle! But the Apostles’ Creed as we now have it cannot go back to the apostles. For one thing, it is not identical word for word with the creed to which this legend is first attached, though clearly it is a later descendent of what we call ‘the Old Roman Creed’. Secondly, neither the Old Roman Creed nor the Apostles’ Creed have been used in the Greek Church, which produced its own formulae, similar in style and pattern but not the same in wording. All these different credal formulae, including the Old Roman Creed as well as Eastern forms, emerge around the turn of the third century, and cannot be traced in earlier Christian literature. We must therefore, look for processes of development, for precursors, and we cannot simply accept the legend at face value. In any case, we know that the agreement to adopt universally the creed known as Nicene, was the outcome of decisions by Ecumenical Councils in the fourth century. So clearly there is an historical process to be investigated, by that stage involving political pressures alongside whatever other factors we may identify.

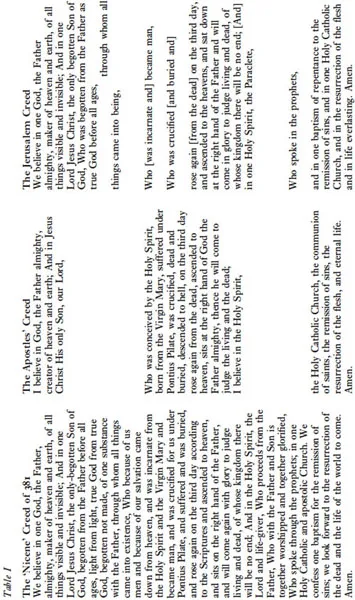

In the doctrinal controversy which led to the formation and adoption of the Nicene Creed, we find people whose doctrines are being questioned or challenged offering in reply what they call the faith they received from their bishop, and then quoting creeds or creed-like summaries of doctrine. There is clear evidence that what lies behind this is the system of training for baptism and initiation into the church. From the middle of the fourth century on, we have a number of series of Lenten lectures surviving from various parts of the Christian world which give us information about how converts were prepared for baptism: after three years as ‘hearers of the word’, they would be allowed to attend the local bishop’s lectures leading to the rite of initiation which took place on Easter night, so that the baptizand would die with Christ and rise with him on Easter Sunday morning. Clearly this practice goes back a century or more at least. The extant lectures are usually in the form of a commentary on the creed, so various local creeds can be reconstructed from them; and during the process, the candidates apparently had to memorize the creed, so as to recite it back before being accepted and baptized. Undoubtedly this is the context in which the familiar credal form was first framed and used. After the adoption of the Nicene Creed, the local creeds survived, and became Nicene by the insertion of the particular agreed formulae into each: that seems to be the way the creed of Constantinople (the one we now use as the ‘Nicene’ creed) arose, it then being adopted as the official version at the Council in 381 because it had a more developed clause about the Holy Spirit than the formula agreed at the earlier Nicene Council in 325. Creeds did not originate, then, as ‘tests of orthodoxy’, but as summaries of faith taught to new Christians by their local bishop, summaries that were traditional to each local church and which in detail varied from place to place. Typical variations can in fact be observed simply by comparing the two creeds we know from their continuing usage, for as we have already noted, the ‘Nicene’ creed is a local Eastern creed adopted by the Council of Constantinople, and the ‘Apostles’’ Creed is a descendent of the Old Roman Creed, the creed in use in the church at Rome at a comparable date (see here).

Such a comparison reveals a number of interesting points. What they have in common is the three-part structure, clauses about God the Father, about the Son of God and about the Holy Spirit. Neither of them, however, has an explicit doctrine of the Trinity spelled out systematically: the three ‘characters’ in the story are described and implicitly related to one another, but the word Trinity is not used, and there is no exposition of the doctrine of God as Three-in-One. There is a sense in which the creeds are not themselves a system of doctrine. The variations confirm this observation: the discrete points are perhaps less important than the bearing they have on the whole. It’s as though the essential content is indeed a story, and as we all know, there are various ways of telling the same story depending on the selection of material, if not the artistry of the narrator. These features are important pointers to the fundamental nature of the creeds: they are summaries of the gospel, digests of the scriptures. As Cyril of Jerusalem put it in his Catechetical Lectures (V. 12), ‘Since all cannot read the scriptures, some being hindered from knowing them by lack of education, and others by want of leisure, . . . we comprise the whole doctrine of the faith in a few lines.’ These were to be committed to memory, treasured and safeguarded, because ‘it is not some human compilation, but consists of the most important points collected out of scripture’.

But if the creeds were intended as summaries of scripture, they have an unexpected shape: there is no summary of Israel’s history as God’s chosen people, no summary of the life and teaching of Jesus, etc. And if there are variations, there are also surprising similarities in detail. The similarities and divergences can be further observed if we add to our two well-known specimens, the creed reconstructed from Cyril’s Lectures (and we could add a good many more). In fact, the ‘Nicene’ creed shares some features of Cyril’s creed which are typically Eastern: the concern about the creation of the ‘invisible’ or spiritual world, as well as ‘heaven and earth’; the stress on the pre-existence of Christ as the Word through whom all things were created. It also has one Eastern feature not evident in Cyril’s, the provision of an explanation – ‘for us men and for our salvation’. Unlike many Eastern creeds, however, including Cyril’s, it shares with the Roman creed stress on the Virgin Mary and the Holy Spirit as the means of incarnation. So there are variations but also identical details, and there is a common tri-partite shape. How are all these features to be accounted for?

It seems that the creeds took the form they did in response to the situation in which they arose, that the selection of details related to the challenges presented to the Christian account of things (a point to be fully explored in subsequent chapters), and the common ‘catch-phrases’ are deeply traditional in oral confessional material pre-dating the formation of the creeds.

The creeds took the form they did in response to the situation in which they arose, namely the context of catechesis and baptism. About half a century earlier than our first evidence of creeds, we find that at the moment of baptism, three questions were customary, to each of which the candidate would reply, ‘I believe’ (quoted from Ps.-Hippolytus, Apostolic Tradition):

Dost thou believe in God, the Father Almighty?

Dost thou believe in Christ Jesus, the Son of God, who was born of the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was crucified under Pontius Pilate, and was dead and buried, and rose again the third day, alive from the dead, and ascended into heaven, and sat at the right hand of the Father, and will come to judge the quick and the dead?

Dost thou believe in the Holy Ghost, and the holy church, and the resurrection of the flesh?

After each response and therefore three times in all, the candidate was dipped into the water and submerged. The custom was no doubt based on the dominical command to baptize in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit (Matt. 28.19). These questions are sometimes referred to as ‘interrogatory creeds’, and the more familiar credal forms as ‘declaratory creeds’. Exactly what the relationship between the two is, and how the move from one to the other took place, is not clearly documented. The liturgical use of the questions at the moment of baptism survived alongside the development of the creeds and the custom of memorizing a creed and reciting it back before baptism. Whatever the exact relationship, it seems likely that the universal three-part shape of the creed is accounted for by the traditional and well-developed practice of the three questions. It is likely that the detailed content of the three questions showed some of the same local variations, and it is not surprising to find different creeds with the same basic shape emerging as a result of this background.

The common ‘catch-phrases’ are deeply traditional in oral confessional material pre-dating the creeds, and their selection relates to the challenges presented to the Christian account of things. Already in the early second century, we find ‘creed-like’ summaries in the works of Ignatius of Antioch:

For our God Jesus Christ was conceived by Mary according to God’s plan, of the seed of David and of the Holy Spirit; who was born and was baptized that by his passion He might cleanse water. (Ephesians 18.2)

Be deaf when everyone speaks to you apart from Jesus Christ, who was of the stock of David, who was from Mary, who was truly born, ate and drank, was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, was truly crucified and died in the sight of beings heavenly, earthly and under the earth, who also was truly raised from the dead, His Father raising him . . . (Trallians 9)

. . . being fully persuaded as regards our Lord, that he was truly of David’s stock according to the flesh, Son of God by the Divine will and power, begotten truly of the Virgin, baptized by John that he might fulfil all righteousness, truly nailed in the flesh on our behalf under Pontius Pilate and Herod the Tetrarch . . . that through his resurrection He might set up an ensign . . . in one body of His Church . . . (Smyrnaeans 1.1–2)

What is noticeable here is the emphasis on the true human birth and true human death of Jesus: undoubtedly the selection and the emphasis were determined by the fact that Ignatius confronted people who were suggesting that Jesus was a kind of human disguise for the truly divine or spiritual Christ, and neither birth nor death were real, a heresy known as ‘docetism’. It was such distortions and challenges which affected the selection of certain details. But it is also noticeable that the different creed-like passages exploit certain stereotyped ‘catch-phrases’, some but not all drawn from scripture, which have clearly been used because they ‘ring bells’ with people, they are part of the traditional ‘in-language’ of Christian teaching and worship. At the same time we are not dealing with quotations of a fixed creed, rather with flexible summaries built up as occasion demanded from stereotyped formulae. The other noticeable feature is that these summaries are not Trinitarian in shape, but are clearly precursors of the second clause of the later fixed credal formularies.

Once alert to this kind of material, we can trace it already in the New Testament: from the very beginning, the Christian communities developed a stereotyped in-language to summarize their fundamental teaching or tell their particular story. So Paul seems to ‘quote’ or adapt traditions and common confessions:

. . . Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures, and he was buried, and was raised on the third day according to the scriptures, and he appeared to Cephas, then to the Twelve, then to more than five hundred brothers at once . . . then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles . . . (I Cor. 15.3ff.)

. . . Concerning his Son, who was born of David’s seed according to the flesh, who was declared Son of God with power by the Spirit of Holiness when he was raised from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord, through whom we have received grace . . . (Rom. 1.3ff.)

Christ Jesus who died, or rather has been raised from the dead, who is on the right hand of God, who also makes intercession for us . . . (Rom. 8.34)

Such passages can be paralleled by many others, not just in the authentic writings of Paul – take, for example, I Peter 3.18ff.:

For Christ also suffered for sins, the just for the unjust, to bring us to God, slain indeed in the flesh but quickened in the Spirit . . . Who is on the right hand of God, having ascended to heaven, angels, authorities and powers having been subjected to him.

There are good grounds for finding the origin of the set phrases of the creed in such stereotyped confessional language and to see it as deeply traditional, despite the absence of evidence for fixed credal formulae in the early centuries.

From such stereotyped material, selection was made to confront challenges to the ‘over-arching story’ that enabled Christians to make sense of the world. A couple of generations later than Ignatius we find a number of Christian writers from different parts of the world referring to the Rule of Faith or the Canon of Truth – Irenaeus in Gaul (modern France), Tertullian in North Africa, Origen in Egypt. This title is given to summaries of the faith which are clearly not fixed – Irenaeus cites it in several different forms, which use different shapes, different selections of details, different stereotyped phrases, but which cover essentially the same ground, and are most typically used to contrast true Christian teaching with the ‘knowledge falsely so-called’ of the heretics. The particular struggle which provided the context for these will be explored further in the following chapter, but their bearing on the formation of creeds can be observed if their variable and yet consistent texts are carefully pondered (see here and here).

A number of points can be regarded as clear:

1. T...