1

5 July 2011

Not the Morning News

Though it could claim to be one of the most important front page stories the Guardian newspaper had ever published, there are four important ways in which its front page exclusive about the hacking of murder victim Milly Dowler’s phone by News of the World was not really news.

Figure 1.1 Guardian, 5 July 2011

First, in a pedantic technical sense by the time the presses rolled late Monday night and early Tuesday, the Guardian’s story wasn’t new. As the article history on the Guardian website makes clear the story had broken online at 16:29 Monday afternoon. Within minutes news of the hacking of Milly Dowler’s phone was tweeted by thousands and appeared as breaking news on TV channels and radio stations. Within hours it was the subject of comment and analysis, supplemented by more revelations from other newspapers, websites and broadsheets throughout the world. Whatever ‘news’ means – a concept as elusive as ‘modernity’ or time itself – by the criteria of novelty, currency or immediacy the print publication of the front page on Tuesday morning was already ‘old news’.

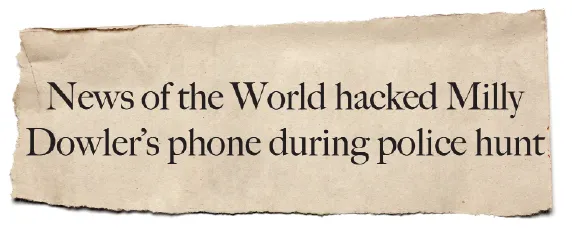

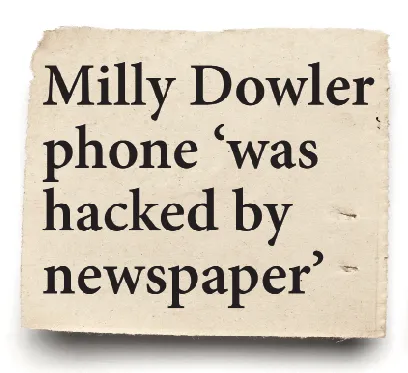

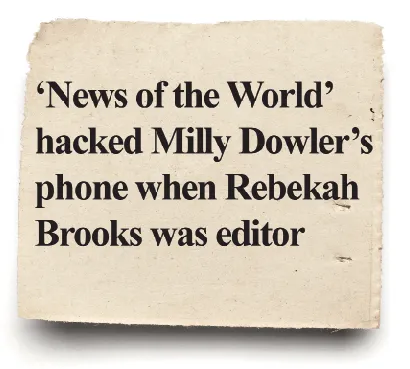

Second, in terms of ‘newsworthiness’ there might seem to have been a rare consensus among the broadsheets about their headlines on Tuesday 5 July.

Figure 1.2 Daily Telegraph, 5 July 2011

Figure 1.3 Independent, 5 July 2011

Figure 1.4 Financial Times, 5 July 2011

Figure 1.5 The Times, 5 July 2011

In one way or another, all the broadsheets covered the Milly Dowler story on their front pages. But they are only a fraction of the market: the Sun, Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, Daily Star and Daily Express have a circulation of around 7.5 million, compared with 2 million or so who buy the Daily Telegraph, The Times, Financial Times, Guardian and Independent. For the bulk of Britain’s newspaper readers the Milly Dowler story was distinctly not news.

If the market is the final measure of newsworthiness, then a picture of Prince William embracing his wife after a canoeing trip was nearly four times more important than the first dramatic act of the hacking scandal, since it dominated the front pages of the mass circulation papers, while Milly Dowler was nowhere to be seen.

Figure 1.6 Daily Mail, 5 July 2011

Figure 1.7 Daily Mirror, 5 July 2011

Figure 1.8 Daily Star, 5 July 2011

Figure 1.9 Daily Express, 5 July 2011

Figure 1.10 Sun, 5 July 2011

Figure 1.11 Metro, 5 July 2011

Third, and most significant, the extensive hacking of the mobile phones of royalty, celebrities, politicians and people in the public eye was already a very old story. If you wanted to know the reality of phone hacking, or indeed what happened to Milly Dowler’s phone when she disappeared in 2002, all you had to do was read between the lines.

Milly

Accessing mobile voicemail messages without permission has been illegal in the UK since the Computer Misuse Act 1990, which carries a two-year prison sentence as a maximum penalty and has no ‘public interest’ defence. However, throughout the early nineties when mobile phones became ubiquitous, several newspaper scoops were derived from some kind of interception and recording of analogue phone signals. The two most famous are a six-minute bedtime ‘Tampon’ conversation between Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles on a mobile phone (recorded December 18 1989 and published by the Sunday Mirror and the Sunday People in 1993) and the Squidgygate tape of a private conversation between Princess Diana and a close friend (published by the Sun in 1992).

In 2000 the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) made intercepting a message while ‘in the course of transmission’ illegal. Around this time mobile telephony shifted from analogue to digital and intercepting encrypted signals required expensive technology, generally only available to the security services. However, a back door was left open: voicemails could be accessed remotely through a pin number. Much like the default admin passwords left on computers in the eighties, these pins were often left unchanged from their defaults. One of the first to discover this loophole was Steve Nott who alerted various newspapers to the security breach. As he claimed under oath to the Leveson Inquiry, the newspapers decided to use the security breach for ‘their own purposes’ rather than publish the story. Even phone users who changed their pin codes were still vulnerable to simple password attacks, with data such as dates of birth culled from other sources. If that failed, a bit of social engineering could solve the problem; dedicated investigators could ring the mobile phone service provider, either pretending to be the customer or an employee, and get the pin code set to default.

On the evening of 21 March 2002 after their 13-year-old daughter Milly failed to return from school, Bob and Sally Dowler rang the police. Within twenty-four hours a nationwide search for Milly was launched, and soon videos and photos of the missing teenager were broadcast on prime-time television. The News of the World which, under the editorship of Rebekah Brooks and her deputy editor Andy Coulson, had built a reputation for covering child murders, began a furious campaign.

Figure 1.12 News of the World’s Milly Dowler story, 14 April 2002

Three weeks after Milly’s disappearance, in the first edition of the News of the World on Sunday 14 April, a major story by-lined by Robert Kellaway had some interesting details.

To any casual reader the details of the messages, not only their content, timing and more importantly the tone of the callers, indicate that these have been listened to by the journalist. It’s not even concealed. There’s no suggestion of a police source. The News of the World, arrogating command of the investigation and trying to sell up a scoop, seems to know more about Milly than the police.

We now know that Milly was already dead, murdered by Levi Bellfield and dumped in Hampshire woodland where her body would not be found for two years.

Figure 1.13 News of the World article by Robert Kellaway, 14 April 2002

We also know now that senior editors of the News of the World were at that time ‘110 per cent’ convinced they knew where Milly was on the basis of hacking her voicemail. One of these was a message from a ‘recruitment caller’ offering a job and (according to the Wall Street Journal) the Sunday paper had sent out eight reporters and photographers to stake out an ink-cartridge factory in Epson for three days. When Milly failed to turn up, and investigations proved that Milly wasn’t even on the factory’s books, the News of the World – stumped for any story – came up with a new scandal: that some hoax caller had rung the factory impersonating a recruitment agency.

Later editions of the News of the World changed the original story, removing some of the more incriminating detail, adding some minimal fact checking. The recruitment company wasn’t a hoax caller, they’d just come up with the wrong number for a client seeking work. But still the tabloid persisted in churning the non-story into a lurid smear: someone mentally disturbed had now called the recruitment agent impersonating Milly.

News is a rough draft of history and a breaking story is like a series of jotted notes, but this scribbled nonsense covers old errors with new: the paper had missed the simple explanation of a wrong number call. A police investigation of this would have quickly discounted the red herring. But the News of the World wanted its sensational exclusive and didn’t want to divulge its illegal source, so clumsily tried to cover its tracks. It would continue to pepper its pages with useless speculation for the next two weeks. When their persistent interference with a missing person investigation failed, and they were eventually ignored by Surrey Police, the newspaper sought retribution by suggesting in print the investigating officers were incompetent.

In the past, tabloid newspapers have been accused of acting like judge and jury during criminal trials, but here we have them acting like the leading investigators during a major murder inquiry (the concatenation of errors, followed by bluster and threats toward the police are forensically documented by Tim Ireland on his Bloggerheads site). Most disturbingly, the paper used its access to illegal information to encourage Milly’s parents that she was still alive and even pressure them into delivering an exclusive interview.

For those who have eyes to see, it’s clear that even ten years ago the Sunday tabloid considered itself better than the police and above the law, which of course they were in more ways than one. It also must have been blindingly obvious to any journalist, police officer or senior News International management at the time that Milly’s voicemail had been hacked by News of the World.

Wilful Blindness

Throughout the early noughties, there was plenty of other evidence of phone hacking lying around in plain sight. The Daily Telegraph did a database search of the British Newspaper Library in Colindale and came up with dozens of articles with direct mentions of phone messages from public figures such as Sven-Göran Eriksson, Ulrika Jonsson, Jude Law, Chris Bryant, Chris Tarrant, Ronaldo, Prince Harry and his girlfriend Chelsy Davy, including precise dates and locations. As Tim Ireland points out, the hacking of young murder victims’ phones seems to go back to 2001 when the text messages of 15-year-old Danielle Jones formed the basis for another News of the World story.

Days after News International journalists were disturbing the police’s attempts to trace Milly Dowler, at a newspaper awards ceremony sponsored by the mobile telephony giant Vodafone, the then business editor of the Sun, Dominic Mohan, thanked the mobile phone company’s ‘lack of security’ for providing exclusives for his rival, the Daily Mirror. It may have been a jest, but it certainly wasn’t a joke.

A few months later, in November 2002, detectives from the newly created Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) found a cache of records implicating various newspapers in illegal access to police and government records from a private investigator in south England. Raiding a second private investigator, Steve Whittamore, the officers of Operation Motorman found extensive evidence of requests from major British newspapers for information. There were hundreds of journalists making hundreds of request for illegal searches of private medical records, social security details, pin numbers and bank accounts. When the senior investigating officer asked his boss why his office weren’t charging the newspapers in question with criminal offences, he was told by his boss they were ‘too big to take on’.

In January 2003, Andy Coulson replaced Rebekah Brooks (then Wade) as editor of News of the World while she took over its daily sister paper, the Sun, as its first female editor. Both of them appeared, along with Murdoch and Les Hinton, then chief executive of News International, before the House of Commons DCMS select committee in March 2003, which was preparing a report on media intrusion and privacy. Questioned by Chris Bryant, Member of Parliament for Rhondda, Brooks admi...