eBook - ePub

Clinical Success in Early Orthodontic Treatment

Antonio Patti, Guy Perrier D'Arc

This is a test

Share book

- 124 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clinical Success in Early Orthodontic Treatment

Antonio Patti, Guy Perrier D'Arc

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Establishing the most favorable moment to initiate orthodontic treatment requires an understanding of craniofacial anatomy and development as well as some training in child psychology. This manual explores these concepts in detail to address when treatment should begin, which techniques should be used, how to form a precise diagnosis, and how to choose the therapy best suited to a patient.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Clinical Success in Early Orthodontic Treatment an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Clinical Success in Early Orthodontic Treatment by Antonio Patti, Guy Perrier D'Arc in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Orthodontie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| Normal Growth |  |

Elements of Growth

We shall give our principal attention to the skeleton, which has been the object of the bulk of craniofacial research and is relatively easy to measure. There is no doubt that the enveloping soft tissues exert important influences on the skeleton, but these are difficult to measure directly. The methods available for studying growth utilize animals (dyed slides of tissue; evaluation of hormonal, hereditary, and dietary factors; and surgery) and humans (embryologic, genetic, and, especially, cephalometric studies).

Two types of growth

Some bones of the cranium and the face are of cartilaginous, or endochondral, origin. Others begin as membranes and are thus formed by different types of calcification, a distinction that persists only until the end of the growth period. It is important to differentiate between these two types of growth because endochondral growth is regulated, in large part, by hereditary factors, while membranous growth responds readily to forces emanating from the surrounding environment, although its prefunctional form is guided by genetic determinants. The cranial base, which develops from the primary activity of its oriented sutures, is a good example of endochondral bone growth. The bones of the cranial cap, in contrast, are membranous in origin. They are also separated by sutures, but these sutures function only secondarily to fill in the spaces that arise as growth proceeds and the developing cranial bones are propelled outward by the developing cerebrum.

Controlling factors

Growth is controlled by general and local factors. General factors include genetic, hormonal, neural, nutritional, health, and socioeconomic influences. Local factors include cartilaginous, osseous, muscular, and aponeurotic structures and functional forces.

Cranium

Here discussion will be limited to the growth of the cranial base, which is the point of support for the whole face. The cranial base consists of the horizontal portion of the frontal bone, the crista galli apophysis of the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, the sphenoid bone, the petrous segments of the temporal bone, and the body and the lateral masses of the occipital bone. These osseous segments are separated by synchondroses, which are active growth centers. Their orientation can be transverse or longitudinal so that they can grow in both length and width. Because it is placed obliquely, the spheno-occipital suture also allows growth in height. Surface bone remodeling can occur through apposition and resorption of osseous tissue as well as through the action of the synchondroses.

The angulation of the cranial base can influence the position of the maxilla and the mandible. This is what Björk (1963) has called “anterior rotation” or “posterior rotation” of the face. No therapeutic efforts can affect the growth of the cranial base because its outcome depends, essentially, on hereditary factors.

Middle third of the face

The bones of the face develop in two ways: by sutural growth and by remodeling.

The sutural system that unites the various osseous units of the face with each other and with the cranial base is fairly complex. These sutures are syndesmoses, which unite primarily bones that are membranous in origin. They have no inherent growth potential but, as is the case at the cranial cap, they behave like “automatic joints of expansion and shrinkage that operate through adaptive connective tissue proliferation and marginal calcification” (Delaire 1971, 1978). These are the “functional units” that Moss (1982) asserts have the primary responsibility for the movement and development of the osseous segments. Making these phenomena complex are the great number of syndesmoses, the variation in their orientations, the variation in the timing and extent of their activity, and the rapid decrease in the intensity of their action as growth proceeds.

Remodeling, which becomes more important as sutural activity declines, is expressed as surface apposition in some regions and resorption in others. It leads to morphologic changes, which include the development of the sinuses.

Mandible

The mandible is primarily a membranous bone that forms around Meckel’s cartilage, which, after serving as a guide for development, disappears. The growth of the mandible takes place partly in response to the activity of condylar cartilage and partly through recontouring.

Alveolar processes

The alveoli have traditionally been considered to be osseous tissue that is created when the teeth appear and disappears when they are lost.

The dental arches develop by heavy apposition of bone, tied to the development of the dentition. The arches diverge posteriorly, thus increasing their volume enough to accommodate the erupting molar teeth.

The growth of the alveolar processes contributes significantly to facial height. Once established, the transverse dimensions of the arches are more or less constant. The distance between the canines becomes fixed between the ages of 8 and 10 years.

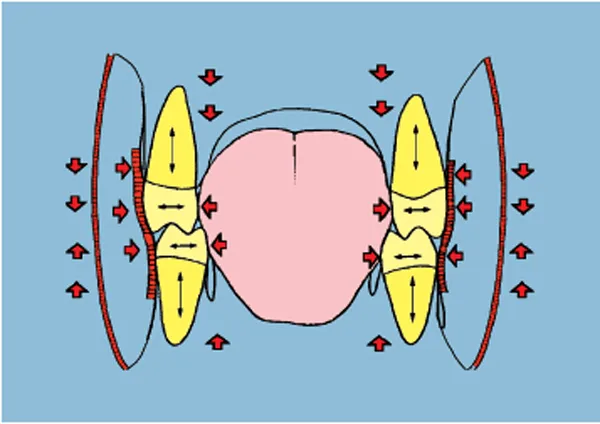

The dentoalveolar arches respond to stimuli from the musculature and from other surrounding centrifugal and centripetal functional forces generated by the tongue, lips, and cheeks; from the extrusive action of erupting teeth; and from the intrusive action of the muscles of mastication that model and shape them by forming what Chateau (1993a) calls the dental corridor and Gugino (2000) refers to as the neutral zone (Fig 1-1).

Facial type

To study the malformations that afflict young people, orthodontists must understand facial types so that they can predict the way a face will evolve, formulate a treatment plan, and establish a prognosis. Apparently similar malocclusions should be treated differently in patients whose typology is dissimilar.

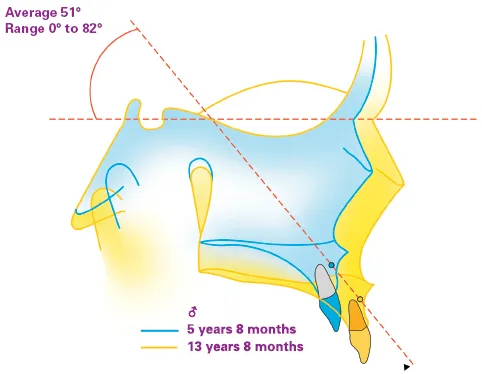

Björk (1963) has described facial typography in detail. According to him, the maxilla should move downward and forward away from the cranial base, making an angle of 51 degrees with the sella turcica–nasion line (Fig 1-2). In fact, this angle can range from 0 to 82 degrees, which means that, during the period observed (5 years 8 months to 13 years 8 months), the displacement can be entirely horizontal or virtually vertical with respect to the cranial base. The average value is only relative; individual variations, which are frequent, must be taken into account.

Fig 1-1 The dental corridor, or neutral zone.

Fig 1-2 During growth, the maxilla moves downward and forward away from the cranial base, according to Björk (1963).

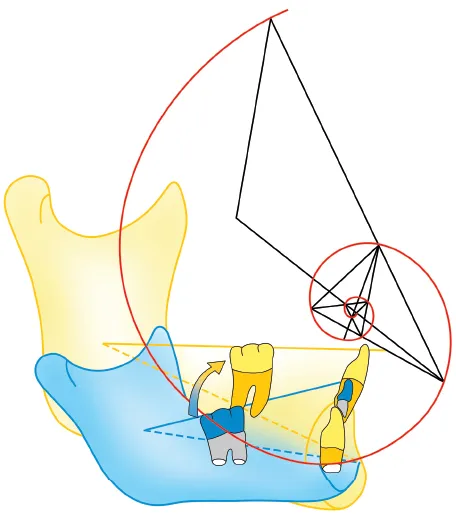

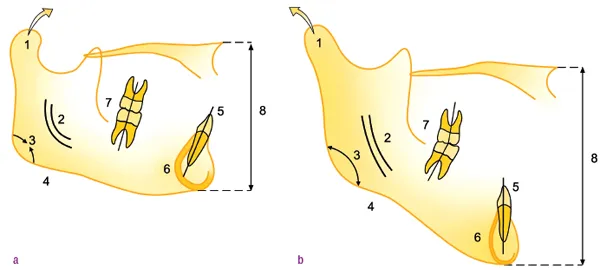

For the mandible, Björk’s classic description (1963) posits two opposite typologies that he called anterior mandibular rotation and posterior mandibular rotation (Fig 1-3). These variations arise from differing patterns in the vertical growth zones, which are the maxilla and the posterior segments of the mandibular and the maxillary alveolar processes.

Condylar growth alone propels menton forward. When this impetus joins with vertical alveolar growth, menton tends to move backward and forward.

When the two growth zones do not operate in harmony, the mandible rotates. Growth is normally most active in the region of the alveolar processes. If growth of the condyle outpaces that of the posterior alveolar process, the mandible rotates counterclockwise; as a result, menton advances, an incisal overbite might develop, and lower facial height will be diminished. On the other hand, if alveolar growth is greater than condylar growth, the mandible will rotate clockwise. Menton will move downward and backward, and lower facial height will increase.

Molar height not only influences the vertical position of menton but also to a great extent controls, by its anteroposterior position, the degree of mandibular rotation. This explains why vertical anomalies are often responsible for anteroposterior discrepancies and why, clinically, the orthodontist should be careful to monitor and control the vertical dimension during treatment.

By analyzing cephalometric radiographs, the orthodontist can determine a patient’s facial type (see chapter 4 on cephalometrics). Ricketts (1961) described a brachyfacial type that corresponds to anterior mandibular rotation, a dolichofacial type that corresponds to posterior mandibular rotation, and a mesofacial type that corresponds to the average type.

Fig 1-3 The two types of mandibular growth and their characteristics, according to Björk (1963).

Fig 1-3a Anterior mandibular rotation: (1) condylar head oriented high and forward; (2) mandibular canal with exaggerated curvature; (3) closed mandibular angle; (4) inferior border of mandible without pregonial notch; (5) symphyseal axis oriented upward and forward (axis of mandibular incisors not in harmony with symphyseal axis); (6) thick subcortical plate; (7) open posterior interdental angles; (8) diminished lower facial height.

Fig 1-3b Posterior mandibular rotation: (1) condylar head oriented high and backward; (2) mandibular canal with mild curvature; (3) open mandibular angle; (4) condylar border of mandible with pregonial notch; (5) symphyseal axis inclined upward and backward (axis of mandibular incisors in harmony with symphyseal axis); (6) thin subcortical plate; (7) closed posterior interdental angles; (8) increased lower facial height.

Rate and rhythm

When orthodontists treat young children, these patients will be going through periods of rapid growth that will often make greater overall contributions to changes in facial appearance than the treatment itself. The orthodontist must determine not only the patient’s facial type but also the direction, rate, and amount of facial growth. The orthodontist can also obtain useful information by evaluating statural growth, because the face in general, the maxilla, and especially the mandible grow at the same rate as the body as a whole.

The maxilla stops growing before statural growth terminates, but the mandible continues to increase in size even after full stature has been reached ...