![]()

Part One

Theorizing sensation

![]()

1

Framing Shakespeare’s senses

Bruce R. Smith

The opening lines of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night give us an especially suggestive subject for framing the senses. For a start, all five of the traditional five senses are engaged: taste, hearing, smell, vision, and touch:

ORSINO

If music be the food of love, play on,

Give me excess of it, that surfeiting

The appetite may sicken and so die.

That strain again, it had a dying fall.

O, it came o’er my ear like the sweet [sound]1

That breathes upon a bank of violets,

Stealing and giving odour. Enough, no more,

’Tis not so sweet now as it was before. [Music ceases.]

O spirit of love, how quick and fresh art thou

That, notwithstanding thy capacity

Receiveth as the sea, naught enters there

Of what validity and pitch soe’er

But falls into abatement and low price

Even in a minute. So full of shapes is fancy

That it alone is high fantastical.

CURIO

Will you go hunt, my lord?

ORSINO What, Curio?

CURIO The hart.

ORSINO

Why so I do, the noblest that I have.

(1.1.1–17)

The attendant’s name is ‘Curio’. No less curious than the number of senses alluded to in the fifteen lines of Orsino’s opening speech is their concatenation – or rather their tide: in quick succession, heard music is metamorphosed into tasted food, music into the touch of breath upon violets, the breath’s touch into the violets’ smell. As with the sea, fluidity is all. Even diction and syntax are fluid, as /s/ sounds dissolve one word into another and the sounds of /hart/become alternately a hunter’s deer and a lover’s dear.

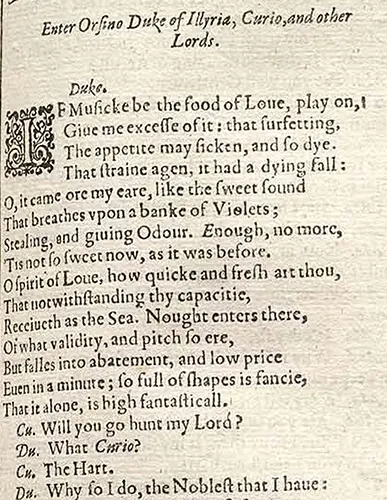

The situation becomes more complicated still when we encounter this passage in the first printed text of the play in Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (aka ‘the First Folio’, 1623). It appears on signature Y3r, the first page of the play (Figure 1.1). To us in the twenty-first century, the exoticism of the medium – an antiquated typeface realized as inked depressions on wavy rag paper – makes it difficult simply to see through the printed text into an imagined fiction, as we might in a modern printed edition of the text. Instead, we are apt to stop at the surface. If we are fortunate enough to encounter a physical exemplar of the folio first-hand, we can touch and even smell the text. In effect, we find ourselves pausing at the door of Twelfth Night and looking through the doorframe. From that vantage point, we confront not only representations of senses within the fiction but the physical means of those representations and our own situatedness in the act of perception.2

Figure 1.1 Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (London: Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623), sig. Y3 (detail). By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Moving back from the printed surface of Orsino’s speech, we encounter, quite literally, a series of frames (Figure 1.2). The text is surrounded on all four sides by rule-lines. A horizontal rule separates the title and another rule separates the text into two columns. Within these larger frames further rule-lines frame the play’s title, the indication of Act 1, Scene 1 (‘Actus Primus, Scaena Prima’), the text of Act 1, Scene 1, and the indication and text of Act 1, Scene 2 (‘Scena Secunda’). Gerard Ginette has demonstrated that these ‘paratexts’, these indicators before and alongside the text, are not the incidental design features we might assume but cues as to how the text is to be apprehended. Paratexts serve, in Ginette’s view, as ‘a threshold, […] a zone not only of transition but also of transaction’.3 In the case of the First Folio, readers are guided by the paratext to frame the text along the lines of classical comedy and tragedy. Lukas Erne in Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist has argued that Shakespeare conceived of his plays as to be read as well as acted, and Charlton Hinman has demonstrated that the printers of the 1623 First Folio, Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, grandly began each play with some version of ‘Actus Primus, Scaena Prima’ as if Shakespeare were Plautus, Terence, or Seneca – or Ben Jonson, whose 1616 Works had marked such divisions. (In the case of most plays Jaggard and Blount failed to follow through.4)

Figure 1.2 Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies (London: Isaac Jaggard and Edward Blount, 1623), sig. Y3. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Five successive critical frames suggest themselves as ways of getting our bearings vis-à-vis Shakespeare’s senses: (1) philosophical, (2) historical, (3) mimetic, (4) mediational, and (5) phenomenological. Let us take Orsino’s speech as a test case. This will involve some potentially dizzying shifts between big ideas on the one hand and the particularities of Orsino’s speech on the other. The result should be an estrangement of this familiar text.

Philosophical

The first frame turns attention to what has been thought through systematically about the senses. Scholars in disciplines such as history and English are apt to treat philosophers’ arguments as historical and cultural artefacts, but the object of philosophy as an academic discipline is the truth about things, irrespective of historical and cultural differences. It matters, of course, which philosophies of the senses seemed most pertinent to early modern Europeans, but it matters even more what range of philosophies were available to choose among. I would distinguish four such possibilities: (1) suspicion of sense experience vis-à-vis rational thought, as exemplified in Plato’s Timaeus and Phaedrus and in writings by Plato’s medieval and Renaissance followers, (2) acceptance, even celebration of sense experience in materialist philosophies such as that espoused by Epicurus and redacted and disseminated in Lucretius and later writers, (3) non-judgemental investigation of sensation as an object of study, as exemplified in Aristotle’s De Sensu et Sensibilibus and De Anima and in early modern medical treatises, and (4) considerations of the ethics of sense experience, as exemplified in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Poetics and in the writings of Cicero and his Renaissance successors.

The fourth group of philosophical framings of the senses have to do with the core meaning of the Greek word ethos as custom, habit, and character.5 Aristotle in Poetics 39.b.3 limits the term to the utterances of tragic protagonists: ‘character’ [ethos] is that kind of utterance which clearly reveals the bent of a man’s moral choice (hence there is no character in that class of utterances in which there is nothing at all that the speaker is choosing or rejecting), while ‘thought’ is the passages in which they try to prove that something is so or not so, or state some general principle.6 In Aristotle’s account, character and thought are more heard than seen. Beyond the individual, the term ethos can also be applied to groups of people and the social institutions they inhabit. Different ethoi cultivate different regimes of sensation. With respect to sense experience, what a playgoer experienced at a Globe production of Twelfth Night was different from what the gentlemen of the Middle Temple experienced in the play’s first known performance in Middle Temple Hall on 2 February 1602, as Jackie Watson investigates in this volume (224–44). Differences in the physical surround and social custom in each place fostered different configurations of vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste.

The sensuous materialism of Orsino’s speech – its unapologetic delight in sense experience – illustrates perfectly the Epicurean strand in Western philosophy. Condemnation of that impulse from a Platonic standpoint seems largely absent from Twelfth Night. Instead, the emphasis falls on ethos, on Illyria as a place for indulgence of the senses – an indulgence that ends, however, in an uneasy reconciliation with strictures of ideal forms and social hierarchy in the play’s concluding scene.

Historical

Included within the second critical frame is not just social history but what early modern Europeans understood as ‘natural history’: literally, the historiae or ‘stories’ that explain living things, including the human body and its senses. The images of air and fluids in Orsino’s speech – the sound of music ‘breathing’ upon violets, the ebbs and flows of the sea, above all the reference to love as a ‘spirit’ – gesture towards the hydraulic conception of the human body in Galenic physiology and psychology.7

When Orsino apostrophizes the ‘spirit of love’, he is referring not only to a mythological deity (Love-with-a-capital-L) but to a mundane body fluid. The body’s communication system was imagined to be an aerated fluid called spiritus. When Orsino declares ‘So full of shapes is fancy, / That it alone is high fantastical,’ he is again being quite physical with respect to the early modern natural history of the senses. In the Galenic scheme cognition was imagined to be a process that began with excitations of the body’s external sense organs, which were communicated internally to the brain by spiritus, where they were fused into synaesthetic imagines through a faculty called ‘the common sense’, into which memories were added to produce phantasmata (or ‘fancies’), which were then communicated by spiritus to the heart, where a whole-body experience of approach or avoidance was decided and communicated, again by spiritus, to the brain, which directed the sensing subject’s response. The ‘shapes’ that Orsino mentions are phantasmata.

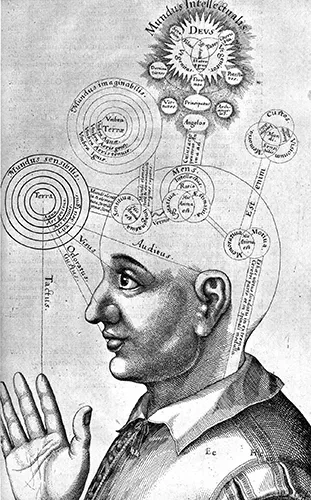

Robert Fludd in his encyclopaedic Utriusque cosmi majoris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atque technica historia (1617–24) offers a diagram that illustrates this process of fusion (Figure 1.3). Particular organs of the head are associated with particular domains of knowledge. Hand, nose, eyes, and ears are connected to Mundus Sensibilis (or ‘the world that can be sensed’), the fore part of the brain to Mundus Imaginabilis (or ‘the world that can be apprehended in images’), the mid part of the brain to Mundus Intellectualis (or ‘the world knowable through ratio, through reason’), and the rear of the brain to memory. Faculty psychology has long ago been discarded as a concept that explains the workings of the brain, but Fludd’s image seems prescient with respect to cognitive mapping via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). In the context of this volume of essays, one pertinent feature of the image is its insistence that different senses produce different kinds of knowledge. Perhaps the most suggestive, however, is Fludd’s charting the interior workings of the brain as three Venn diagrams in which two or more of the image’s external worlds are merged.

Figure 1.3 Robert Fludd, Utriusque cosmi majoris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atque technica historia (Oppenheim: Johan-Theodor de Bry, 1617–24). Wikimedia Commons.

Orsino’s ‘high fantastical’ is as much a physiological state as a poetic posture. Theseus in A Midsummer Night’s Dream describes what happens when sensation overwhelms reason:

Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends.

The lunatic, the lover, and the poet

Are of imagination all compact.

(5.1.4–8)

In terms of early modern psyc...