eBook - ePub

Crisis

One Central Bank Governor & the Global Financial Collapse

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An authoritative insider's perspective, this book penned by the governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand chronicles the global financial and economic meltdown. A well-researched and dynamic firsthand account, it captures the drama of the events—from the overheated markets of 2007 through the collapse of investment banks and crises in multiple economies to the fragile recovery in New Zealand and the world in 2010—as politicians, bankers, and government officials struggled to deal with the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. This updated edition also reveals how New Zealand grappled with the impact of debt crises in the United States and Europe as well as with the devastating effects of the Christchurch earthquakes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crisis by Alan Bollard,Sarah Gaitanos in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Conditions. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The End of the Golden Weather

The Background, 1987–2007

The peaks of the Grand Tetons are sharp against the Wyoming sky. Below the mountain range, moose and elk graze the rolling grasslands and bears wander freely; in the Snake River, trout swim and beavers build their dams. As I took in the scene from the old US Forest Service lodge in Jackson Hole, I hoped that I would have time to paint and hike.

But I was not visiting for rest and recreation. It was August 2005, and I had been invited as governor of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand to a conference of the United States Federal Reserve.

Normally life is peaceful here, but today is all hustle and bustle. Outside the lodge, big white trucks with satellite dishes prepare to beam interviews to the world. The front door swings open before a group of muscular young men with crew-cuts and security wires plugged into their ears. In their midst is a much older man in his late seventies, short and balding with owlish glasses. Holiday-makers stop and respectfully move to the side, gawping. After the United States president, this is probably the most powerful man in the world: Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Board of Governors of the mighty Federal Reserve System of the United States.

He is here to address the annual Jackson Hole symposium of the Federal Reserve, an event at which 150 central bankers, economists and commentators discuss the world economy. In the mornings there are serious presentations; later, conference participants may go hiking. On the mountain trails one hears the direct views of people with their fingers on the world’s economic pulse. In the evenings they barbeque on the terrace and the economic discussions continue.

This is not just another event for Alan Greenspan. He is shortly to retire after an unprecedented eighteen years heading the most powerful economic body in the world. In his honour, the conference is entitled ‘The Greenspan Era’. The great man himself opens proceedings. He gives a masterly exposition, loaded with detail and statistics, as is his style, on how the American economy has evolved since the 1960s. He describes how financial markets and monetary policy have become more sophisticated, helping economies to become more stable while countries enjoy the fruits of globalisation and innovation.

As Greenspan sits down, the journalists dash out of the room to file their copy, transmitted by satellite to the world’s media and thence to the financial markets, waiting to translate his every wink and nod into market prices. Later in the morning Greenspan unexpectedly stands to ask a question; the journalists rush out to file his question as well. Other speakers give presentations, all admiring of the chairman. Their views are summarised by the lead paper from two eminent Princeton University monetary economists, Alan Blinder and Ricardo Reis: ‘While there are some negatives in the record, when the score is toted up, we think he has a legitimate claim to being the greatest central banker who ever lived.’*

Of course, there have always been sceptics. Only two years previously, at the same conference, American academics James Stock and Mark Watson had reported on their investigation into the causes of the higher growth and more stable conditions in world economies over the past decade. In a detailed econometric study, Stock and Watson documented a number of drivers of growth but, to the general surprise of economists, they had been unable to attribute much of the new growth and stability to improved monetary policy.†

This line of argument was well known to the experienced participants. The real insight of the 2005 conference came from another quarter. One of the new breed of financial economists, University of Chicago academic Raghuram Rajan, gave a paper entitled ‘Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier?’* In a word, his answer was yes. Using data from financial instruments, he told a different story to Greenspan’s, a story of rapidly changing financial markets with perverse incentives to mismanage risk and a real chance of major problems ahead. This generated a lot of argument and counter-argument.

To conclude the conference, Greenspan returned to the stand, and this time looked forward. He was more sanguine than Rajan, saying that despite ongoing challenges the current housing boom would inevitably simmer down, savings would start to improve and current account deficits would rebalance. These were reassuring words from someone who had been at the heart of the US economy for decades.

Greenspan had become chairman of the Federal Reserve Board in 1987. This date marked the start of a new growth era in the world economy, the beginning of the largest accumulation of wealth in history. With globalisation, new markets were opening up, dramatically increasing the global labour force; the Uruguay Round gave birth to the World Trade Organization, and both were encouraging developed countries to reduce their trade protection; financial markets – that network of traders, economists, bankers and fund managers – were becoming deeper and more sophisticated; and consumers worldwide were getting access to new and cheaper goods.

This all resulted in stability for the Western world. For emerging economies, however, the decade was volatile: Russian, Mexican and Brazilian debt crises echoed around the financial markets. In July 1997 the stock market in Thailand fell precipitously, sparking what became known as the East Asian Financial Crisis.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) rescue missions to countries such as Indonesia and Thailand recommended tough reforms, including better governance of banks and state enterprises, more open capital markets, freely floating exchange rates and removal of state industry protection and support schemes. But East Asian governments did not much appreciate the lectures they received from international financial institutions and the United States, and they responded in their own fashion, strengthening capital controls, continuing with fixed under-valued exchange rates to stimulate their exports and building up private and official savings as insulation from the next world shock. Initially this combination of protective policies seemed to work. When their solution also resulted in cheap goods and cheap money for the markets of the West, the latter were more inclined to approve. However, some of these policies were to brew later problems in turn.

China led the recovery with strong exporting. The world was now seeing the biggest growth in incomes ever – a typical Chinese worker born in the early 1970s while Mao Tse-tung was still alive was to see his or her income grow by up to five or six times. Unsure about the future, the Chinese population saved strongly. The Chinese Government kept interest rates low and encouraged state banks to lend freely to government and private business ventures. Some of these investments proved to be bad decisions but others were spectacularly successful.

We were seeing the birth of a second industrial revolution and, like the first, it would have far-reaching global implications. Thousands of factories were built, initially along the Chinese coastal plains and then further inland, up river valleys and in cities. Factory owners gained access to cheap capital for set-up costs, then employed cut-price labour from the huge surplus of rural farm workers who were prepared to move, work, save and remit at levels never before seen anywhere in the world. These factories imported components and materials, largely from other higher income East Asian producers, and transformed them into a wide range of industrial and consumer products, based on Western designs, for Western markets. In a short space of time this manufacturing grew in sophistication and scale of production; and the product range widened and improved in quality. Now Chinese plants could compete with other electronics manufacturers in the East and some of the primary processors of Australasia. Manufacturers in the United States found it difficult to compete, as did those in Europe who were similarly assailed by cheap manufacturing imports from the newly opened Eastern European markets.

This industrial revolution provided consumers in the West with a bonanza of products and designs at tantalising prices. Central banks around the world applauded: emerging market exports were so cheap that they helped reduce consumer prices in the West. Many countries were enjoying significant growth without generating inflation. This period became known as the ‘Great Moderation’, referring to the perceived end to major price and output volatility from the mid-1980s. (The term, coined by a Harvard economist James Stock in 2002, was later popularised by Ben Bernanke.) Proponents argued that the phenomenon not only represented a global shift in productivity as it raised growth in the emerging countries, but it also lifted potential growth in the West as better-off consumers could increase production without overheating their domestic economies.

Not everyone was sanguine about this. A couple of well-known central bankers expressed their doubts to me. The gist of their concern was that financial markets were too dependent on the ability of central banks to keep inflation low while growth was so high. It suited these markets to see central bankers as more powerful than we really were. One day they would learn otherwise.

As New Zealand pulled out of the East Asian crisis in 1998, we too saw good times ahead. Initially it looked like the crisis could be very damaging for New Zealand. We were not well positioned: because of rising inflation, Don Brash, in his capacity as governor of the Reserve Bank, had had to increase interest rates just prior to the crash. Our growth prospects took a hit.

But business cycles are the meat and potatoes of economists. As a student in the 1970s I had seen the effects of New Zealand’s refusal to face the facts of a world where our markets were not guaranteed, the OPEC oil shocks, and the excesses of the Think Big energy projects. In the late 1980s, when I was director of the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, I saw the effects of Rogernomics when the Labour Government forced changes on a resistant economy, causing businesses to collapse, exorbitant interest rates and high unemployment. We also suffered the 1987 share market and subsequent commercial property crash. In the 1990s, as chairman of the New Zealand Commerce Commission, I oversaw some change in the dairy, aviation, forestry and other industries, and we were also trying to bed down proper business practices, getting businesses to compete in the interests of New Zealand consumers.

I was appointed secretary to the New Zealand Treasury in late 1997 at the time the East Asian crisis knocked us into recession, but the 1980s reforms had made the economy more flexible and we bounced back quickly. It seemed that at last we might be on a more vigorous growth track. We suffered unnecessary angst over the Year 2000 (Y2K) problem and the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic of 2003 had little effect on the economy. Though the US tech wreck of 2000 was nasty and the events of 9/11 shocking, their economic impacts proved limited. More importantly, we were seeing improved terms of trade because of higher prices for commodities, still the backbone of the New Zealand economy. When that happens, New Zealand grows.

From 1998 to 2002, I inhabited the secretary’s office in the Treasury building at number 1, The Terrace, Wellington. On the top floor, the wood-panelled office had a sweeping view of the Wellington Harbour on one side and the Beehive against the brooding Tinakori Hills on the other. There we worked at Treasury’s ongoing job: keeping the quality of government spending as high as possible and trying to create the best conditions for New Zealand business to grow the economy.

When the new Labour Government entered office in 1999, they wanted more attention to social programmes, but they knew that, to finance them, they needed decent economic growth. Prime Minister Helen Clark questioned me about how we perceived the potential for expansion. She needed to know how fast the New Zealand economy could grow without overheating. Were any of our policies holding us back? Was the Reserve Bank, across the road, with its predominant focus on price stability, too conservative in its view and inhibiting the economy from reaching its potential? Were there other changes our small economy should be making? We New Zealanders have a tendency to self-criticise, although at that time our growth record was actually quite impressive. Through the period from 1991 to 2002 we grew at over 4 per cent per annum, faster than Australia at the same time. But New Zealanders were spending more than they earned, and by 2002 there were signs that inflation was building again.

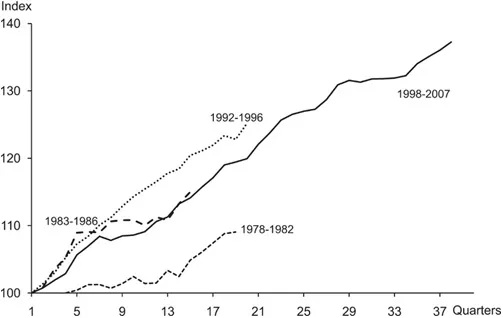

New Zealand enjoys the longest period of growth since the 1950s. The graph shows growth cycles over the last thirty years and illustrates 37 quarters of GDP growth during the ‘Great Moderation’.

On 26 April 2002, I received an unexpected early-morning phone call from Don Brash, governor of the New Zealand Reserve Bank, telling me he was about to move on. With a general election approaching later that year, he was making a dramatic career change. He was to join the National Party, with a guaranteed seat in the House of Representatives. That meant he would leave the Reserve Bank immediately – in fact that very day. The financial markets were taken aback, buzzing with rumour and gossip. I too was surprised.

I did not then realise that I was about to get a much closer look at the workings of the New Zealand economy.

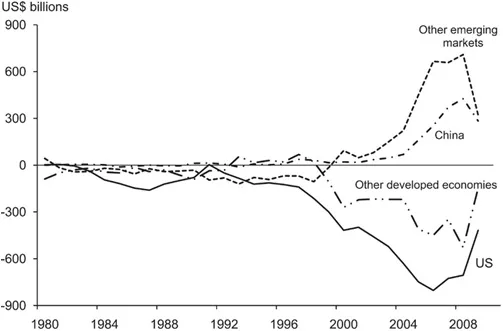

Fast-growing global imbalances: the graph measures the growing current account imbalances by different country groupings.

After the turbulent 1990s, the 2000s seemed to be offering the world a chance to get the growth environment right at last. Strong economies in the East produced for the consumers of the West. Did it matter that some exporting nations were starting to build up large surpluses while some Western countries were recording big trade deficits? Apparently not, because global financial markets now had more sophisticated ways to finance this difference. As the global trade deficits swelled they were matched by bigger flows of global finance than the world had ever seen.

There were a number of key drivers. In the United States, President George W. Bush cut taxes, which had an immediate stimulative effect as Americans consumed more goods, an increasing proportion of them imported. US businesses experienced growth and employment was strong, but what Alan Greenspan had identified as the ‘productivity miracle’ of the late 1990s was fading. With reduced tax revenue, the US Government, which had achieved a fiscal surplus under President Clinton, relapsed into deficit. The US pattern of consumption-led growth was mirrored in other Western countries – in Europe, Eastern Bloc countries began exporting to the consumers of the European Union.

Economists worried about how the huge deficits of the Western countries could be sustained. In 2005, Ben Bernanke, at that time a Federal Reserve Committee member, gave an influential speech about what he described as a ‘savings glut’ in the East, arguing that countries such as China had their own imbalance problems, with too much household saving and too few high-return investment opportunities. As a consequence, the Eastern funding was flooding world markets, looking for returns. By implication, capital was too cheap, and this distorted consumer choices in the United States, exchange rates in Australasia and government expenditure in Western Europe.

Not only the Chinese and other big-saving East Asian countries contributed to the glut; increasingly, so did the oil-exporting nations of the Middle East and former Soviet Union. As the price of oil rose, they built big surpluses. Countries with such windfalls were encouraged by the IMF to set up sovereign wealth funds to manage them, and these funds soon became a powerhouse in world financial markets, with banks, hedge funds and mutual funds recycling massive capital flows each year.

Thus world financial markets were positioned between rampant consumers on one hand and savings gluts on the other. Operating in newly deregulated markets, they searched for new ways to bridge the needs of these two groups. It was a period of intense financial innovation. Northern Hemisphere business schools were turning out young graduates with impressive qualifications, combining finance theory with mathematics and advanced computer modelling to form a new discipline, financial engineering. Attracted by the prospects of huge remuneration, they flocked into the world’s major investment banks, the likes of Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs and Lehman Brothers. They brought with them the pricing and risk-management models developed by Fischer Black and Nobel prize-winning economists Myron Scholes and Robert Merton, among others.

The investment banks encouraged the world’s big lending banks to securitise the assets in their balance sheets; in other words, to bundle their loans and on-sell them to other parties, sometimes through a ‘special purpose vehicle’, a special legal entity designed to meet a particular need. This freed up the banks’ capital so that they could keep lending to new customers. This practice was matched with another class of innovation – new derivative products, by which credit risk could be offset by linking it to other market prices that were more acceptable to the holder. Derivative products were not all the same – many different instruments were devised. In principle, regulations were in place to limit the risks from such developments. But a further innovation – off-balance-sheet ‘structured investment vehicles’ – helped institutions minimise the costs of these regulations.* For these complex instruments to be sold through financial markets, buyers needed to understand how much risk they were taking on, how to manage this risk and how to offset any residual uncertainties. To assist these assessments, the financial engineers devised a number of new risk measures.

Certification of risk levels for buyers came in the form of credit ratings. Financial instruments were examined by big rating agencies, such as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, who would award a rating from triple A down to junk status. Investment banks could then mix and match bundles of debt on the market to reach the necessary quality thresholds to get a triple A. Buyers of this debt might be smaller banks, fund managers or other financial institutions around the world, and they relied heavily on the credit ratings to assess the quality of the packages they were buying.

If they wanted further assurance, then the financial markets offered other ways to reduce risk. Buyers could go to a group of (mainly Amer...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Prefaces

- 1 The End of the Golden Weather: The Background, 1987–2007

- 2 Gathering Storm Clouds: 2007–August 2008

- 3 Bursts, Busts and Bailouts: September 2008

- 4 A Very Bad Week in a Very Bad Month: October 2008

- 5 The Contagion Spreads: October–December 2008

- 6 From Hong Kong to Basel: December 2008–January 2009

- 7 On the Tight Rope: February 2009

- 8 How Bad Could This Get?: March 2009

- 9 The First Green Shoots: April–June 2009

- 10 Fragile Recovery: June–August 2009

- 11 Bring Out Your Dead: October 2009–May 2010

- 12 Troughs and Ceilings: Mid-2010–August 2011

- 13 Shocks and Jolts: September 2010–December 2011

- 14 Crises and Outages: 2012

- Timeline

- Further Reading

- Index

- Copyright Page

- Footnotes

- Backcover