eBook - ePub

The Healthy Country?

A History of Life & Death in New Zealand

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Did Maori or Europeans live longer when Captain James Cook arrived in New Zealand in 1769? Why were Pakeha New Zealanders the healthiest, longest-lived people on the face of the globe for 80 years—and why did Maori not enjoy the same life expectancy? Why were New Zealanders' health and longevity surpassed by other nations in the late 20th century? Through lively text and quantitative analysis presented in accessible graphics, the authors answer these questions by analyzing the impact of nutrition and disease, immigration and unemployment, alcohol and obesity, and medicine and vaccination. The result is a powerful argument about why people live and why people die in New Zealand—and what might be done about it.

The Healthy Country? is important reading for anyone interested in the story of New Zealanders and a decisive contribution to current international debates about health, disease, and medicine.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Healthy Country? by Alistair Woodward,Tony Blakely in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Histoire de l'Australie et de l'Océanie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Before Cook

The Long History of Human Longevity

The old always think the world is getting worse. It is for the young, equipped with historical facts, to point out that, compared with 1509, or even 1939, life in 2009 is sweet as honey. Immersion in history doesn’t make you backward looking; it makes you want to run like hell towards the future.

— Hilary Mantel, The Guardian, 17 October 2009

What is known about human lifespans prior to the arrival of Europeans in New Zealand? In this chapter, we take a long view, beginning with the work of palaeo-demographers who have attempted to piece together life tables for our hunter-gatherer ancestors. We consider the transition to agricultural societies and the consequences for population health, and then focus on conditions among Māori prior to 1769.

The best estimate for Māori life expectancy pre-Cook, based on skeletal remains and what we know about hunter-gatherer and early agrarian societies elsewhere, is about 20 to 25 years. This figure is dominated by high infant and child mortality – those who made it to the age of 20 years could expect to live, on average, another 15 to 20 years.

Finally, we turn to the much more extensive literature on mortality in Europe in the centuries preceding Cook’s journeys to New Zealand. At the time of Cook’s voyages, England and Wales were just starting up the steep slope of life expectancy increase and the average lifespan was around 36 years.

HUNTER-GATHERER SOCIETY

The first traces of modern humans are seen in Africa and they date to roughly 150,000 years before the modern era. For approximately 95 per cent of human existence since that time, our species operated in hunter-gatherer mode. The defining characteristic of this way of life was an exquisite dependence on local resources. How many people, how closely together they lived and how often they needed to move, all this was determined by the food, shelter and water that were nearby. Much of the time the basic population unit, the band, was no more than 20–25 people, but in times of abundance larger numbers might come together. Occasionally, the environment was so productive that lucky foragers could make a good living with what was on hand. The Portage River in modern-day Ohio supported a sedentary hunter-gatherer society about 1200 before present (BP), with ample local year-round supplies of fish, small mammals and birds. But this was unusual. Mostly, hunter-gatherers had to be mobile. However small the group, the food immediately to hand would eventually be depleted and then the band must shift. The need to be mobile conditioned technology (as there were limits on the tools that could be carried from one site to another), economics (surpluses had no value because they were not portable), and population dynamics (wide birth-spacing ensured parents on the move were relatively unencumbered).

Much of what is written about hunter-gatherer society comes from observation of survivor groups in remote areas in more recent times. As agricultural civilisations extended their range, hunting and gathering societies were overrun, absorbed, destroyed or displaced. Those that continued the traditional way of life were pushed to the margins, where food supplies were depleted and unreliable, and living conditions in general were much less favourable. As a result, we should be cautious when extrapolating from present (or recent past) examples of hunter-gathers to the far distant past. Nevertheless, this information makes a necessary and useful addition to our understanding of the long history of human longevity.

Mortality Patterns

Studies of hunter-gatherer populations in the modern era typically report high mortality in early life. Infant death rates may be as high as 300 per 1000, with perhaps half of all live-born children dying before the age of 15 years.38 A comprehensive summary of mortality among ‘ethnographic’ hunter-gatherers (as distinct from Paleolithic populations) found that life expectancy at birth varied from 21 to 37 years.39 For example, the !Kung people in southern Africa in the 1960s and 1970s had an expectation of life at birth of about 30,40 although the figure was rather higher for those born after 1950. The commonest causes of death were infectious disease and trauma. Many of the diseases that are prevalent in modern societies, such as coronary heart disease, diabetes and cancers, appeared to be uncommon.

One might ask: how could a society sustain itself if people lived only to age 20 or 25, on average? The answer is that most of those who survived high mortality rates in childhood lived a good way beyond age 20 or 25. That is, the average age of death (i.e., life expectancy), the median and the mode are quite different in societies with high infant mortality, as shown in the text box in the Introduction. Amongst the !Kung, individuals who had survived to age 20 could expect to live on average another 30 years. Life expectancy at 45 years was around 20 years in five traditional hunter-gatherer populations studied between 1965 and 1990.39

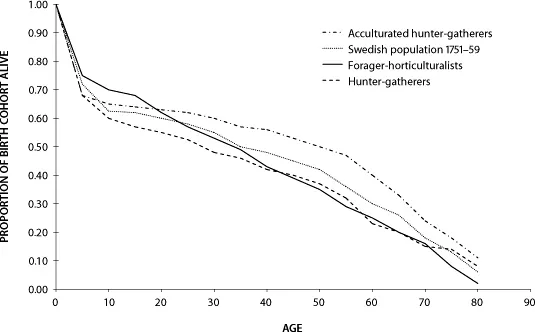

Figure 3 demonstrates the impact of high mortality in early life, drawing on examples of modern hunter-gatherer groups. (Note that ‘forager-horticulturalists’ and ‘acculturated hunter-gatherers’ practise a mix of gardening and foraging.) High child mortality means that only about two-thirds of babies survive to five years of age. However, mortality reduces after this point, and roughly half of those who survive childhood live on into their 40s and 50s. Figure 3 includes information on Sweden in the middle of the eighteenth century (obtained from church records) – note the Swedish survival curve is similar to that calculated for twentieth-century hunter-gatherer populations.

Another source of information on mortality amongst pre-historic communities is studies of skeletons. Bones provide clues to the age at death, the likely cause of death, other diseases that may have been present although not necessarily the cause of death, and past injury. Information is often patchy, because there are relatively few samples. Hunter-gatherer societies, by and large, did not bury their dead in cemeteries. Over-represented are groups that lived in fertile areas (such as the Maghreb peninsula in North Africa), where population density was high and people had no cause to move around. ‘Palaeodemographers’ have used other kinds of evidence too, such as archaeological pointers to the size and density of settlements, and analysis of DNA recovered from bones and teeth.41

Figure 3: Average survival curves for modern (twentieth-century) hunter-gatherers, forager-horiculturalists, acculturated hunter-gatherers and the Swedish population 1751–59

Source: Based on Figure 1d in Michael Gurven and Hillard Kaplan, ‘Longevity among Hunter- Gatherers: A Cross-Cultural Examination’ (Population and Development Review 33, no. 2 [July 2007]: 321–65).

Making sense of skeletal signs depends on some big assumptions. First, the estimation of age from skeletons is accurate, to within a year or so, during adolescence, when there are obvious age-related markers of growth and development. But at older ages, dating depends on measures of wear and tear, bony re-modelling and degenerative changes that are only moderately correlated with age. We assume that the relation between changes in the bones and age has been constant over the history of Homo sapiens, but this may not be the case. It is possible that early hunter-gatherer populations matured more slowly than contemporary humans, as a result of low bodyweights, intermittent shortages of food and high levels of physical activity. If maturation occurred more slowly, then age at death amongst adolescents and young adults would be under-estimated using modern standards for skeletal development.

We assume also that skeletal samples give us an unbiased view of what was happening in the population at large. But there are many reasons why this may not be the case. Studies of recent burial sites, where it is possible to match results based on the skeletal remains with registers of births and deaths, find that cemetery samples are seldom representative.41 Deaths at young ages are commonly under-counted, because children’s skeletons do not endure as well as adults’. On the other hand, cultural mores relating to burial may cause some groups, those with influence and authority in particular, to be over-represented in cemetery samples.

Average age at death (the statistic available from the cemetery studies) is the same as average life expectancy at birth only when the population is in equilibrium, that is, when births and deaths balance, and there is no migration. Of course, this is hardly ever the case: when the birth rate is above replacement, average age at death will under-estimate life expectancy, and vice versa. Think about the base of the population age pyramid, and what happens if it swells (or shrinks). If the proportion of the population in younger age groups is increasing, and there is no change in death rates, there will be more deaths amongst relatively young individuals, and the average age at death will fall (although life expectancy has not changed, since age-specific death rates are the same). Imagine an extreme example, one in which three-quarters of the population was made up of pre-school-age children. Even if these children were relatively healthy, with a life expectancy of 70 years or more, the average age at death would be skewed heavily towards the under-five-years category.

As a consequence, the age distribution of deaths tells us as much about fertility as it does about mortality, especially in the range in which palaeo-demographic data are most reliable.42 The important point is that a change in the birth rate will change the average age at death if the force of mortality remains the same. Therefore life tables based on skeletal samples require not only information on age at death, but also an estimation of the population growth rate.

Bearing in mind these caveats, studies of skeletal remains from hunter-gatherer populations provide estimates of life expectancy ranging from under 20 years to the high 30s. In the Americas, life expectancies for forager populations were rather higher before 1500 BP than in the more recent period (500–1500 BP). In this latter ‘classic’ era, leading up to European contact, in some populations in the Americas more than half the fully grown individuals died before 20 years,43 and life expectancies tended to lie in the range 20–25 years.44

Trauma was a relatively common cause of death. Up to 40 per cent of skeletons in some studies of early hunter-gatherer populations showed signs of violent death, and many ethnographic studies also report that violent deaths (including those due to infanticide, inter-clan conflict and accidental injuries) were relatively common. Samuel Bowles, an evolutionary biologist at the Santa Fe Institute and expert on the causes and consequences of ancient warfare, argues that violence has been a common cause of mortality throughout the history of forager groups. According to Bowles, trauma caused 30 per cent of deaths among the Ache, a hunter-gatherer population living in Paraguay, and 17 per cent among the Hiwi, in Venezuela and Columbia.45 Stephen Pinker estimates mortality from violent causes in some hunter-gatherer societies approached 500 per 100,000 per year (more than three times the rate in Germany during World War II).46 These are very high rates, although the numbers of deaths, in absolute terms, were relatively small because the populations were tiny, by modern standards. We note some anthropologists believe that Pinker exaggerated the frequency of violence in hunter-gatherer and foraging societies as a result of extrapolating too freely from present-day populations that endure in a highly modified form, to the conditions that applied in the distant past.47

We can speculate that patterns of infectious disease changed when humans moved from moist, tropical environments to grasslands and open spaces, and then pole-wards into temperate and sub-arctic zones.48 Modern tropical rain forests provide warmth and moisture sufficient to sustain a rich mix of microbes, with many vectors on hand and ample opportunity for host-hopping. This ecological pressure-cooker ramps up the force and variety of infections. The epidemiology of infectious diseases among modern primates may be a guide to what the first human hunter-gatherer bands experienced: African monkeys are infected with many more species of malaria, for example, than the four that predominantly affect humans. However, being infected is not necessarily the same as being sick. After a long period of co-existence, it is likely that early humans grew to ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Before Cook: The Long History of Human Longevity

- 2 Māori Majority: The First Hundred Years After Cook

- 3 ‘The Healthiest on the Face of the Globe’: Non-Māori from 1860 to 1940

- 4 Decline and Recovery: Māori from 1860 to 1940

- 5 Post-World War II: Convergence

- 6 Mortality Divergence: 1980 to 2010

- 7 Summing Up, Looking Forward

- Conclusion

- References

- Index

- Copyright Page

- Footnote

- Backcover