- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

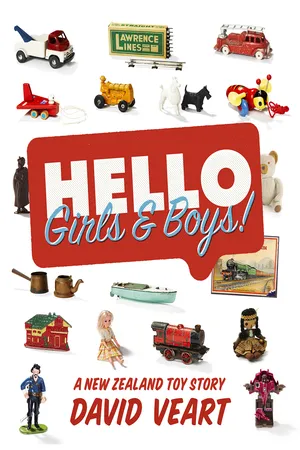

About this book

Toys are fun—but they are also serious business, as David Veart makes clear in this remarkable story of New Zealanders and their toys from Maori voyagers to 21st-century gamers. Deploying the tools of archaeology and oral history, Veart digs through a few centuries of pocket knives and plasticine to take us deep into the childhoods of Aotearoa. His story explores how people made their fun on the far side of the ocean—the Maori and Pakeha learned knucklebones from each other; young Aucklanders established the largest Meccano club in the world; and Fun Ho!, Torro, Lincoln International, and Luvme helped to build a successful local toy industry under the shade of import protection.

Hello

Girls

&

Boys! covers the crazes and collecting, playtimes and preoccupations of big and little New Zealand kids for generations. With its memories of knucklebones and double happys, golliwogs and tin canoes, marbles and Meccano, Tonka trucks and Buzzy Bees, this is a seriously fun New Zealand toy story.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hello Girls & Boys! by David Veart in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781775587637Subtopic

Australian & Oceanian HistoryOut of the Toy Box 1

TOYS FROM THE WAKA

Aotearoa New Zealand was the last major landmass discovered and settled by humans. East Polynesian explorers and settlers first arrived some time in the thirteenth century, bringing with them a highly developed portable culture – a culture which had evolved in the thousands of years since their departure from SouthEast Asia. These people arrived on double-hulled waka, carrying with them their crops (kūmara, yams and taro) and animals (dogs and probably pigs and chickens). They brought skills and tools, songs and toys. People everywhere play – Dutch historian Johan Huizinga even described us as Homo ludens, ‘man the player’ and argued that play is central to the development of culture. The way Māori played, and still play, is remembered and continued through stories, songs and the toys themselves. Knowledge of these ways of play adds to our understanding of the first culture of Aotearoa.

Flying a Kite

Wiremu Kīngi’s huge birdman kite, made in Gisborne in the 1880s for Sir George Grey, looks down upon the visitors to the Māori galleries at Auckland War Memorial Museum – trapped in its glass case, a giant butterfly pinned to a board. But if you look behind the case, a trick of the museum lighting shows that the kite’s shadow has escaped the cage, soaring across the wall, flying as it should over the assembled taonga: waka, whare and toki.

Kites, te manu tukutuku, are the perfect place to start exploring the toys of Aotearoa New Zealand. Kite makers know how to harness the wind, and in the beginning Aotearoa was a place that only people who understood the wind could reach. Kites arrived here on the first waka as part of the portable culture of Polynesian colonisation. They had travelled across the Pacific from the South East Asian homeland and were found wherever Polynesians settled. They had many uses: for fun or fishing, for divination or war, and occasionally as sails, manu whara, to drive canoes.1 A story from Rarotonga in the Cook Islands happily makes the connection between the voyaging waka and kites.

The chief Rata Ariki was putting together an expedition to search for his parents, who had vanished in suspicious circumstances. He started by looking for the perfect tree to build a canoe and when he found it there were many gods waiting for him.

The gods exclaimed, ‘Is it you, O our child? do you desire a canoe?’ Then they further asked, ‘Why do you want a canoe?’ Rata replied, ‘I am going to search for my parents, Vaieroa and Tairiiri-tokerau.’ The gods said, ‘Your parents have been devoured by the sons of Puna; your mother’s eye-balls are in possession of their sister, Te-vaine-uarei; that is so, our child; now return home, and we will make your canoe.’

When the canoe arrived, Rata set about recruiting a crew for this voyage of vengeance. The men he gathered around him sound like an ancient version of an America’s Cup team: rope makers, shipwrights, navigators and helmsmen. Finally a man named Ngănăōa turned up.

‘What do you do?’ asked Rata.

Ngănăōa said, ‘I fly kites.’

Rata said, ‘You fly kites; and what then?’

Ngănăōa said, ‘I leap up to the heavens and extol my mother with exalting song.’

Rata said, ‘You extol your mother, and what then?’

Ngănăōa replied, ‘O, I exalt our mother, and that is all.’

Rata said, ‘I do not want you, you cannot come.’ He forthwith threw Ngănăōa overboard and sailed his canoe out to sea.2

Rejecting the fool was a big mistake; in stories from around the world, it usually is. Although Rata had men in his crew with a multitude of practical skills, he had left Ngănăōa, the holy fool, the tohunga, the kite-flying wind master, behind.

Luckily for Rata, Ngănăōa was a difficult character to get rid of. He turns up again and again in the story to rescue Rata and his crew from, among other things, a giant octopus, man-eating sharks and a giant clam. With Ngănăōa’s assistance, Rata Ariki reaches his destination and avenges his parents’ deaths. Kite flying in this story becomes a metaphor for the ability to control unseen powers, whether they be winds or taniwha.

Kites appear in many Pacific stories. Māui, half man, half god and pan-Polynesian trickster, was a kite flyer. So, too, was Tāwhaki, who appears in many tales. In some versions he is the grandson of Whaitiri, the female deity who personifies thunder. Often he attempts to reach the heavens – once to search for his grandmother, once for his missing wife. First he climbs Aratiatia, the path to the sky, with his brother Karihi, but the latter falls and is killed. Then Tāwhaki makes another attempt, this time riding on a kite, but because the kite is manmade he cannot finish the journey and in a subsequent attempt he falls and is killed.3

Throughout the Pacific kites were usually made with aute, the bark of the paper mulberry, which is also used to produce tapa. Paper mulberry trees were such an important part of the Polynesian cultural kit that the voyagers brought seedlings to Aotearoa, together with such basic foods as taro and kūmara. The generic name for Māori kites was manu aute, the name still given to Wiremu Kīngi’s giant at the Auckland Museum. In New Zealand, however, the paper mulberry did not grow very well – the bark cloth became so valuable that small pieces were used as earrings and Tupaia, the Tahitian priest who travelled with James Cook on the Endeavour, could calm tense confrontations with Māori by offering pieces of the very valuable bark cloth brought by Cook in large quantities from Tonga.4

This ūpoko tangata is named for the material it is made from – cutty grass. A humble child’s toy kite made by Ngāpuhi iwi from Northland, it is an unusual survivor.

There were, of course, many other materials suitable for local kite making, and Māori exploited them all. Raupō leaves replaced aute in many places; cutty grass and flax were also used. Māori made the frames of kites from kareao or supplejack, mānuka and toetoe.5 As soon as European materials became available local kite makers used them, too. Both the surviving birdman kites use European cloth or paper in their construction.

Kites were an important part of Māori work and play, but our knowledge of them is limited. This is partly because kites, by their very nature, are ephemeral things. While perishable materials like wooden carvings may occasionally survive in the right conditions, kites do not, and humans tend to look after the precious rather than the mundane. Worldwide, there are now only seven examples of Māori kites that predate the early twentieth century, kept in museums in London, Hawai‘i and New Zealand. They include three manu taratahi, special triangular kites with one point, which were flown when Ruhanui was celebrated, the time when the kūmara was stored and gifts were given.6 The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa has an example of a rectangular child’s kite, ūpoko tangata.

On Top

Gods, chiefs, ariki – all these people of power used artefacts that we would call toys, but for purposes transcending play. When examining toys within the Māori world, the status and social rank of the people involved must be taken into account because their mana affects the story. When Pākehā arrived in Aotearoa they found a complete society, consisting of all social levels from the equivalent of aristocracy to peasantry (and a little later with a king as well): all these people are remembered with ‘toys’.

But Pākehā commentators described what they saw from their own class and cultural perspective: toys equal children. When describing Māori society they ignored the very similar ‘toy stories’ within European aristocratic circles; the rich and powerful have time to play. Marie Antoinette had her play farm, wealthy eighteenth-century dinner guests were entertained by complex and hugely expensive automata and well-heeled Edwardian middle-class gents like H. G. Wells played with toy soldiers on the drawing room floor. This involvement of adults in toy play is something that would re-emerge only in the late twentieth century, when wealth and leisure in Aotearoa returned to the level enjoyed by Māori aristocracy two centuries before.

New Zealander Brian Sutton-Smith, who became a world authority on children’s play, started his research into New Zealand children’s games during the 1940s, when it was still easy to find people with memories stretching back into the nineteenth century. He attempted to assess what changes had occurred in Māori toys and play and which ones had survived this Pākehā winnowing of tradition.7

To do this, he concentrated on toys and games that he described as having survived the ‘cultural disintegration’ of the nineteenth century when, especially after the passing of the Native Schools Act in 1867, Māori children fell increasingly under Pākehā influence. He noted that there were many surviving games and toys but also some that appeared to be later introductions – non-traditional activities seen as beneficial and educational that had been encouraged by the Young Māori Party in the 1890s and ‘phys. ed.’ section of the Education Department in the 1930s. The Māori toys that had survived, he believed, were those which had a Pākehā equivalent and which missionaries and later teachers could not view as ‘uncivilised’ and discourage or ban.

The elaborate carving on these poutoti from the Bay of Plenty indicate the high status of the person who once owned them.

Similarly, the ethnographers chose not to record games that were either too difficult to describe or, in their eyes, had sexual connotations. Surfing, whakahekeheke, was done using kōpapa, small boards about the size of modern boogie boards, or kelp bags or occasionally small waka. But the pastime became a victim of missionary prudery and fell from favour because the participants surfed naked. Māori comedian Billy T. James once did a sketch in which, as a child, he was presented by a practical relative with a pair of shorts with one pocket cut out, so he had ‘something to wear and something to play with’. This story has a rich traditional origin: one of the games avoided by missionary and ethnographer alike was rito ure, in which the erect penis (or stiffened finger) was skilfully looped with string to the accompaniment of music. There were other prohibitions on play: early ethnologist Elsdon Best recorded one kaumātua telling him that ‘We were not to spin our humming tops on Sunday’.8

Among the survivors of this culling, puritanical or otherwise, Sutton-Smith listed knucklebones (see p. 60), stilts, tops and string games, as well as other adventurous pastimes that required little in the way of equipment: hunting, sliding, ‘pipi shell skipping’ (more like flying pipi shells, which I remember from my own childhood, requiring a dexterous flick of the fingers) and a number of games played with the hands – the Māori equivalents of paper, stone, scissors. On occasion traditional games survived even without Pākehā equivalents: he cites hand games played by older workers in East Coast shearing gangs. He does not mention kites. They may have fallen from use, but modern Māori commentaries on play and toys suggest that many more survived, under the radar of both Smith and the missionar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Out of the Toy Box 1 Toys from the Waka

- Out of the Toy Box 2 New Arrivals, 1840–1900

- Out of the Toy Box 3 Toys in Depression & War, 1900–1945

- Out of the Toy Box 4 A Golden Age? 1946–1960

- Out of the Toy Box 5 Toys to the World, 1960s–1970s

- Out of the Toy Box 6 The Elves & the Rogernomes, 1980s

- Out of the Toy Box 7 End Games, 1990s–2000s

- Conclusion Toys in the Joined-up World

- Notes

- Sources & Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Image Credits

- Index

- Copyright Page

- Backcover