![]()

CHAPTER 1

Context and classifications

It is generally accepted that Mayday, 23 May 2007 is the date that the global human population passed a significant milestone, when the number of people living in cities exceeded the rural population for the first time. A major feature of this demographic shift is that denser cities result in greater built form, with more hard surfaces and less green space, landscape areas and permeable surfaces. Even in Australian and New Zealand cities, where the average household has decreased from 5.3 to 2.6 people over the last 100 years, residential subdivision lot sizes are reducing dramatically, while the average physical size of individual dwellings is increasing, leaving little room for vegetation or habitat.

The demographics and lifestyles of the current generation are quite different to earlier generations, with people now marrying later, living longer and enjoying more cosmopolitan lifestyles. The environment of our cities has been adapted to these conditions with the provision of promenades, outdoor cafes, meeting places and entertainment areas, but this has put greater pressure on the natural environment, especially endemic ecosystems.

These dramatic changes in population densities and the urban environment are helping to fuel the unprecedented climate change currently taking place, while, in turn, the damaging impacts on the urban environment are being exacerbated by this climate change. The results of globally increasing temperatures, melting of the polar icecaps and rise in sea levels, among other devastating impacts, will be felt most severely in cities and urban areas, including those of Australia and New Zealand. The Garnaut Climate Change Review commissioned by the Australian Government in 2007 warned that ‘On a balance of probabilities, the failure of our generation on climate change mitigation would lead to consequences that would haunt humanity until the end of time’ (Garnaut Climate Change Review 2008). This warning still stands, despite the failure of nations to make any binding commitments at the Copenhagen Climate Summit in December 2009.

One way of creating more natural environment within cities and helping to mitigate climate change, as well as accommodating the other competing pressures for space, is to use the rooftops and vertical surfaces of buildings. Rooftop gardens or green roofs have been long established in Europe, and were more recently introduced to North America and Asian countries, such as Japan and Singapore. Australia and New Zealand have a relatively short history in this area, but are now embracing the move towards green roofs and walls and, while there are some climatic differences to consider, the technologies being developed in the southern hemisphere have particular relevance to northern hemisphere summers and to this time of globally changing climate.

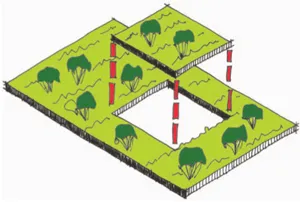

A green roof replacing ground-level green space

The concept of green roofs is very simply illustrated by the diagram above, where the footprint of a building is replaced with a green roof, with no net loss of green open space or habitat. Living walls on the vertical surfaces of the building can further add to this positive environmental effect. Together, green roofs and walls create a living architecture, where the formerly inert built form of concrete, steel, timber and glass comes alive – breathing, cooling, cleansing and recycling.

Green roofs and living walls are, of course, not the only answer to all our environmental problems, but are part of a broader urban green infrastructure (instead of the usual engineered infrastructure) approach that integrates a range of methods and processes to address stormwater management, temperature control, pollution reduction, reclamation of urban wastelands, public health and lifestyle, and also provides a raft of economic benefits. Through carefully designed green infrastructure, we can create and modify microclimates within cities, making these environments more habitable to humans and other fauna and flora.

Later in this book, we examine the context of the living architecture of green roofs and walls within city-wide green infrastructure, but firstly we look directly at the rooftops and walls that surround us. We start with a brief historical perspective to provide some understanding of the origins of living architecture. We will consider green roofs within an international, and then Australian and New Zealand, context, followed by a similar appraisal of living walls. A brief summary of the terminology of green roofs and living walls follows.

International context of green roofs

The earliest references to green roofs relate to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and other roof gardens on stone temples that were developed around 600 BC in Mesopotamia. These provided a green, cooling effect in the hot arid climate of the Middle East. In contrast, in cold northern Europe during the Viking era of around 800–1000 AD, sod roofs were implemented, where ‘turf, and occasionally seaweed, was used to line the walls and roofs of homes for protection from harsh winds, extreme cold, and rain’ (Peck 2008).

In the early 1900s, internationally influential architects Swiss-born Le Corbusier and American Frank Lloyd Wright included rooftop gardens and terraces in some of their projects, with particular emphasis on using these spaces as outdoor living rooms. For instance, Wright’s Larkin building in Buffalo of 1904 included a paved roof garden, and in 1930 Le Corbusier completed the Beistegui apartment in Paris, featuring a surrealist-inspired roof garden. Reference was made to this international architectural movement in Adelaide’s Advertiser newspaper on 13 April 1907, in an article titled ‘Flat roofs and roof gardens – a suggestion to Adelaide householders’. Several commercial roof gardens planned for Adelaide and a proposal for the City of Unley Town Hall were mentioned (Aitken 2009).

Between the World Wars, two international gardens stand out as particularly significant: the Derry and Toms Department Store roof garden in London and the Rockefeller Centre series of roof gardens in New York, which were completed in the mid 1930s (Osmundson 1999).

The Second World War saw a virtual halt to large-scale building projects, including any significant rooftop garden development, so it was not until the 1960s when there was a revival in the green roof industry. This was particularly evident in Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Norway, occurring as a counter to the decline of green space and the harshness of the urban environment.

The German green roof movement also led to the development of lightweight, extensive green roof systems during the 1970s-1980s. Formerly green roofs were mainly intensive, comprised of a relatively deep growing medium that supports high plant diversity, and requires regular maintenance. In contrast, extensive systems are low maintenance, being comprised of shallow, lightweight growing media suitable for tough, drought-tolerant plant species such as sedums.

Grin Grin horticultural complex, Fukuoka, Japan

Subaru’s Singapore headquarters 4WD testing track on rooftop

Arguably, North America has become as significant as Europe today in terms of implementation of green roofs, with cities including Toronto, Vancouver, Chicago, Boston, Portland, Phoenix, Washington DC and New York virtually exploding with a dazzling variety of projects. However, it is probably in Singapore and Japan that some of the most innovative and experimental projects are occurring, particularly in cities such as Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka and Fukuoka.

In South Korea and China there are a number of new towns and eco-cities planned, incorporating green roofs as part of their focus on sustainability. For instance, a new multi-functional administrative city is being created in Korea, based on the visionary design by Balmori Associates and Haeahn Architecture. The design features an extensive series of interconnected green roofs as an integral part of the city master plan aiming to ‘merge together art, landscape, and form and ... create public spaces that allow people to interact with nature’ (Merkel 2007). Although such exciting developments point to a potential green roofs and walls super-movement in Asia, some projects have stalled because of unachievable timeframes and budgets. As climate change takes hold, and the need to mitigate the environmental problems of large cities becomes even more crucial, the expansion of the green roofs and living walls industry seems assured, albeit within a sustainable timeframe and context.

Australian and New Zealand context of green roofs

Australia and New Zealand have the advantage of an extensive body of worldwide research and project precedents to draw upon, plus the challenges of relatively small population and economic bases, in addition to specific climatic extremes that require some different approaches and solutions to those suitable for the northern hemisphere. Indeed, we need to look firstly within our own lands and histories to develop ideas and directions that have the most relevance for us.

In both Australia and New Zealand, settlement by the British occurred in relatively recent times, with Australia’s colonisation dating from 1788, and British sovereignty secured in Aotearoa New Zealand with the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. The Australian Aborigines and the Maori – the original, traditional owners of each nation – have a history of using a wide range of natural resources within their respective, climate responsive, vernac...