![]()

1. The significance of the Old Testament

What’s in a name?

The Christian Bible is traditionally divided into the Old and New testaments.1 ‘Testament’ comes from the Latin testamentum, which, in Latin versions of the Bible frequently translates the Hebrew and Greek terms for ‘covenant’.2 This terminology indicates that a key point of distinction between these two sections of the Bible is the new covenant relationship between God and his people, which is promised in the OT (Jer. 31:31) and inaugurated through the death and resurrection of Jesus (e.g. Luke 22:20), and the earlier covenant relationship embodied, primarily, in the covenant between God and Israel at Sinai.3 This contrast is evident in passages such as 2 Corinthians 3:4–18, which contains one of several references to the ‘new covenant’ (Gk kainē diathēkē, v. 6),4 and the only specific biblical reference to the ‘old covenant’ (Gk palaia diathēkē, v. 14). The parallel here with the reading of ‘Moses’ (v. 15) suggests that ‘old covenant’ here refers to the books of the Law (the Torah or Pentateuch).5 Similar language appears in Hebrews 8:7–13, where the ‘new covenant’ (vv. 8, 13) is contrasted with the earlier covenant that is ‘obsolete’ (v. 13, from the Gk palaiō, ‘to grow old’).6 This gives some biblical warrant for the term ‘Old Testament’, though in a limited and fairly negative context. The use of the expression to refer to a wider collection of biblical texts appears to have been coined later, during the patristic period; one of the earliest references to ‘Old Testament’ is by Melito of Sardis, in the second century ad.7

The designation ‘Old Testament’ may indicate that it is no longer relevant or has been superseded by what follows, and to emphasize its continuing significance as part of the ‘canon’ of Christian Scripture,8 it has been suggested that ‘first testament’ is a more appropriate term.9 However, ‘Old Testament’ has persisted in common usage.

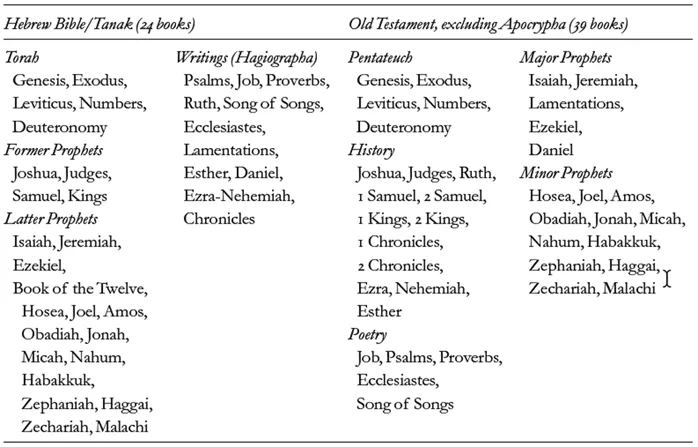

The expressions ‘Old Testament’ and ‘first testament’ are distinctively Christian. They suggest that this collection of texts is incomplete on its own, and points forward to the ‘New Testament’ and the fulfilment of all that has gone before in and through Jesus Christ. In recent years the term ‘Hebrew Bible’ has become increasingly popular.10 This description is not strictly accurate, since parts of the text are in Aramaic (Ezra 4:8 – 6:18; 7:12–26; Jer. 10:11; Dan. 2:4 – 7:28), however, it does emphasize that before it became part of the Christian Bible it was, and continues to be part of the canon of Jewish Scripture. And its pre-Christian origin needs to be taken into account in interpretation.11 This designation is more acceptable to Jews, and promotes discussion between Christian and Jewish interpreters of what is, essentially, the same text. Another term, ‘Tanak’, is an acronym based on the three sections of the text of the Hebrew Bible: Torah (Law), comprising Genesis–Deuteronomy (the Pentateuch); nĕbî’îm (Prophets), which is further divided into the former prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings – which, in the Hebrew text appear as single books), and the latter (or writing) prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and the twelve minor prophets); and kĕtûbîm (Writings or Hagiographa), comprising Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ruth, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah and Chronicles.12 However, as with the term ‘Old Testament’, ‘Tanak’ also has a confessional aspect: the Hebrew text of both is the same, but its readers reflect the faith communities to which they belong. This confessional stance may not have a direct impact on the exegesis of individual passages within their historical context, where some degree of objectivity is important. It is significant, though, for the way those texts are understood within their wider biblical context, and particularly in the area of biblical theology.13 It is argued that by referring to the text as the ‘Hebrew Bible’, those confessional elements that may be less acceptable to other groups are minimized, thus giving greater scope for scholars from different faith communities to work more closely together.

Differences between Christian and Jewish approaches to the text are evident in two important ways. First, as noted already, although the text is essentially the same, the ordering of their respective canons is different (see Table 1.1). The Tanak ends with Chronicles, which has as one of its key emphases the planning and building of the Jerusalem temple, under David and Solomon. Following a relatively brief review of the history of Judah to the exile and a description of the destruction of the temple by the Babylonians, the book closes with the edict of Cyrus that the temple will be rebuilt (2 Chr. 36:22–23), and in the final sentence the people are urged to ‘go up’ (v. 23). In this way the Hebrew Bible points to a new beginning for God’s people after the exile, linked with the restoration of the religious life of the nation (including the birth of Judaism, which is primarily associated with Ezra). The OT ends with the prophetic books, suggesting a link between the future hope of the people of God and the second part of the Christian Bible.14 In particular the last book, Malachi, points to the coming of the day of the Lord, which will be preceded by the return of Elijah. This opens the way for the NT focus on John the Baptist and his announcement that the kingdom of God has come in the person of Jesus Christ. These are the same Scriptures, but the different canonical ordering means that they prepare their respective readers for different historical fulfilments. These different expectations are seen, too, in the second important distinction: the ways in which the text is read forward into other religious literature. Clearly, Christians read the OT forward into the NT. As noted already, the OT is incomplete without the NT (just as, we could argue, the NT is incomplete without the OT). The Tanak, similarly, is incomplete without later writings, in particular the Mishnah and the Talmud.15

Rendtorff’s observation that ‘we read the same text as the Jews when studying the first part of our Bible in its original language, but we do not have the same canon’16 is significant. It is important not to lose sight of the historical and cultural roots of the OT; it is important, too, to be open to the insights of those who are studying the same texts from a Jewish perspective. It is equally important, though, particularly when looking at the way texts function within the wider biblical canon, to recognize the importance of the confessional context in which the text is being studied. For that reason, I will refer to this part of Scripture, which I read as a Christian, as the ‘Old Testament’, though without the suggestion that it may be considered to be outdated or irrelevant to the life of the church.

The Christian significance of the Old Testament

The first Christians were Jews who viewed the OT as authoritative Scripture. Indeed, for a time this would have been their only sacred text. They recognized the significance of the new relationship with God that was made possible through the death and resurrection of Jesus, and of the new revelation they had received, but they did not discard the OT, which was to them already an important document of faith. On the contrary, a key concern of NT writers was to present the coming of Christ as the fulfilment of OT hope, and to demonstrate continuity both between the faith of the OT and that of Christian believers, and between the people of God in the OT and the community of those who put their trust in Jesus Christ.17 The NT writers were convinced that what God had promised to his people in the past was now being fulfilled in and through the person and work of Jesus, and this gave continuing significance to the OT.

However, as the Christian church moved beyond its Jewish roots it came to comprise, predominantly, Gentiles, who had little or no cultural interest in the OT; and, other than the fact that it was already in circulation as a Christian text, they had no reason to attach religious significance to it. The question for these non-Jewish believers was not how to read what was already an important document of faith in the light of the coming of Jesus but, more fundamentally, why bother with the OT at all? One solution, set out, for example, in the Epistle of Barnabas, was to claim the OT as a distinctively Christian text, which had been misunderstood by the Jews, who interpreted things like the sacrificial and food laws literally rather than spiritually.18 A more extreme solution, put forward by Marcion in the second century, was to remove the OT from the Christian canon altogether.19 Marcion reflected Gnostic thought in presenting a contrast between the inferior God of the OT and the loving Father proclaimed by Jesus. He claimed that the attempt by the early Christian community to emphasize continuity between the Old and New testaments was mistaken. For Marcion, only Paul properly understood the gospel of grace and, as a result, Marcion suggested a canon that excluded not only the OT, but also much of the NT.20 The response to Marcion included an affirmation of the importance of the OT, though still as an essentially Christian document that could be properly understood only in the light of the coming of Christ.21

These two extremes, one that regards the OT, or a substantial part of it, as irrelevant to the life of the church, and the other that seeks to ‘Christianize’ it, are represented in the modern debate. There are those, such as Adolf von Harnack, who have argued for rejecting the OT entirely as a document of the Christian church;22 though the more common approach is to subordinate the message of the OT to the teaching of the NT and to other perceived sources of moral authority, so that any value depends on the OT’s agreement with them. Thus the OT has no authority of its own, and its retention as part of the canon seems more out of historical interest or as a concession to Christian tradition than out of a sense of its own intrinsic worth. In an attempt to give the OT greater value as part of the Christian canon another approach is to interpret it primarily as a witness to Christ and to find direct links between the OT text and the life, ministry, death and resurrection of Christ.23 While of some value, this approach means that the OT is of value only in so far as it can be linked to aspects of NT teaching about Christ. Some OT texts may be open to such a reading, though there is considerable debate about which ones. But does that mean that a text has value only if it can be given such a ‘Christian’ interpretation? A consequence of this may be that commentators and preachers either ignore the large sections of the OT that cannot easily be related to Christ directly, or engage in imaginative and speculatory interpretations in an endeavour to make the link.

One further consequence of recognizing the significance of the OT only in so far as it can be related directly to the NT is that the text may be spiritualized to such an extent that important aspects of its meaning are not developed. So, for example, the Song of Songs (Song of Solomon) is frequently taken to refer to the relationship between God and his people or between Christ and the church. However, it also includes the sexual expression of the love between a man and a woman, and that aspect of the text is rarely expounded. Another example may be the approach to OT sacrifices. Instructions regarding animal sacrifices in the OT are not relevant to the practice of the church today: Christ’s sacrifice makes them no longer necessary. Consequently, OT texts referring to sacrifices may be taken simply to point to their fulfilment in the death of Christ. They do that, of course; but they also contain important spiritual principles, including recognizing the seriousness of sin, the importance of confession, the nature of sacrifice as something meaningful and costly, and so on. These principles need to be recontextualized, but they remain relevant to th...