![]()

THE CULTURE OF WORKING-CLASS AND DEPRIVED AREAS

What does a black teenage girl in London have in common with a retired coal miner in Doncaster? As we have seen, describing the culture of working-class and deprived areas is far from straightforward, because, in reality, there are cultures (plural) of working-class and deprived areas, rather than one single culture. There are the traditional working-class and the benefit cultures, and to these we can add: ethnic differences; age-related subcultures; northern and southern differences; Scottish, Irish, N. Irish, Welsh and English identities; and urban, rural and suburban cultures.

The strengths and limitations of contextualization

This, however, does not mean that it is pointless to outline some common characteristics of the culture of working-class and deprived areas. Indeed, identifying the culture of any group and contextualizing to that culture can be a helpful process, as long as two important truths are borne in mind.

First, every culture is part of a common humanity. Whatever the distinguishing characteristics, people within that culture have characteristics that are true of everyone. They are made in God’s image, an image that they still reflect to some degree, by God’s common grace, even though that image is now marred by sin. They enjoy the goodness of God’s world and long for the relationships for which they were made. They are all broken people, sinners who face the judgment of God, and they are the victims of the sins of others.

Secondly, every person is a unique individual. Whatever the distinguishing characteristics of a particular culture, people within it have aspects of personality and interests that are unique to them. They may be a truck driver who likes opera or an unemployed teenager who loves reading. Each person is different and part of a matrix of relationships that is unique to them. So, while cultural descriptions may be commonly true, we cannot assume they are true of the person in front of us. We need to contextualize on a person-by-person basis.

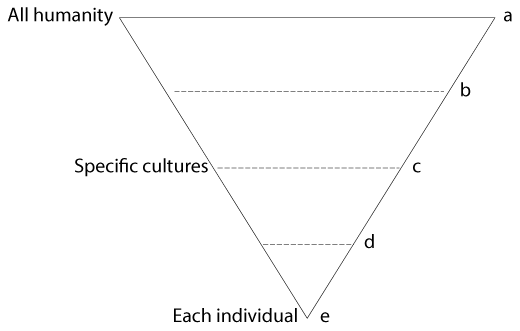

You can see this through the following diagram.

Everyone is both part of our common humanity (‘a’) and a unique individual (‘e’). In between these two realities, we can slice the triangle at different points, thereby including varying numbers of people. We can, for example, slice it at point ‘c’ and describe the culture of people from working-class and deprived areas. This would produce some useful descriptions that would be generally true of people from this culture, though we must remember that everyone is different and not all our generalizations will be true all the time. Or we can take a broader cultural group, such as British people (‘b’). Here we can identify some generalizations that are true of both working-class and middle-class Brits. Or we can take a narrow slice at point ‘d’ and describe the culture of urban rap music or northern working men’s clubs.

Three implications follow.

First, we need to remain confident that the gospel is ‘the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes’ (Romans 1:16). Everyone is part of our common humanity (‘a’), sharing a common identity as God’s image-bearers, facing the common problems of human sin and divine judgment, and needing a common Saviour. Whatever marks out a particular culture as different, everyone needs the gospel and everyone can find in the gospel the hope of salvation.

Secondly, we must always treat people as people, not in an undifferentiated way as generic representatives of a social class. We cannot let our cultural analysis harden into presuppositions or prejudices. It is important to heed the warning of one gospel worker on a council estate in Sheffield: ‘I struggle with some of the material that is produced to try to help people in this area, as I think it often generalizes people too much.’

Thirdly, generalized cultural descriptions are helpful tools, because often they speed up the process of person-specific contextualization, and there are sufficient common cultural characteristics to make contextualization worth pursuing. Whatever the differences among people from working-class and deprived areas, they do not invalidate the process of considering their common traits. The French are heterogeneous, but it is still useful for missionaries to France to learn about French history and think about contextualizing to French culture. In the same way, working-class and deprived areas are heterogeneous, but it is still worthwhile for those working in these areas to think about contextualizing.

So we can helpfully describe specific cultures, as long as we remember both: (a) that every individual is unique – in some respect like no-one else; and (b) part of a common humanity – in some respects like everyone else.

So, in the light of the above, in this chapter we will identify:

- some common characteristics of people from working-class and deprived areas (level ‘c’ in the diagram);

- some tools to help people undertake their own context-specific cultural analysis (level ‘d’ in the diagram).

Common characteristics of working-class and deprived areas

1. Anti-authoritarianism

People from the above areas often have few positive experiences of authority. They may come from families where parental authority is dysfunctional or they may have had negative experiences at school and work. Their experience of the state is likely to be either that of threat or an unwieldy bureaucracy. Parents often side with their children against teachers. Many will have experienced crime without redress, which, in turn, blurs attitudes towards criminality. ‘If an individual is in generational poverty, organized society is viewed with distrust, even distaste. The line between what is legal and illegal is thin and often crossed.’ They do not recognize the category of ‘loving authority’. This makes relating to God as Lord difficult. It means that the proclamation of the kingdom or government of God is not heard as good news.

2. Entitlement mentality

The benefit system has created many people who are used to others providing for them. Need equals expectation: someone will meet that need. So they can easily see the church as another ‘service-provider’. Talk of ‘caring for one another’ can be interpreted in terms of entitlement.

3. Reputation

People in these areas often define themselves by their place in the social strata. It is of utmost importance to be somebody, to be respected. People are happy when there is equality, but, when someone has more than you, then you ‘need’ what they have. Reputation is everything. So, for example, some people from such areas will avoid using charity or thrift shops. Identity is linked to appearance, so you avoid buying second-hand clothes. Among the middle class, in contrast, identity is tied to education, achievement and worldview.

4. The struggle

Struggle is a major theme in the life of many people from the above areas. It is not just that life is hard, but the fact of struggling forms part of their identity. Indeed, they interpret their lives in terms of this struggle. Problems are part of ‘the struggle’, part of what it means to be a person in a deprived area. The identity of the enemy or oppressor may vary, but, in general terms, it is the struggle against the system or against fate. ‘The struggle’ reinforces other characteristics: a victim mentality and low aspirations.

5. Victim mentality

People often see themselves as victims, with little power over their lives. Because they feel powerless, they may resist the system by being passive-aggressive rather than aggressive in a combative way.

This victim mentality means that any failings in my life are the failings of other people. Shame is not so much a concern for the wrong done to others, but the inability to be the person I want to be, or to accept the person I am. As a result, any talk of guilt is seen as an attack on me. So, even when you highlight my guilt, I can still see myself as the victim.

This is not to deny that people are victims. But we must encourage them not to make victimhood their identity. Victimhood can be attractive because it allows individuals to avoid responsibility for their actions. But only true repentance will lead to forgiveness and freedom, and repentance only comes when people take responsibility for their sin.

6. Limited aspirations

Middle-class lives are more likely than working-class lives to see hope for change. Not always, of course, because many middle-class people also struggle with depression and other issues. But middle-class individuals are more likely to believe that, if they work hard, then they can succeed. Models of success abound. But those from deprived areas see little prospect of change. To have ambitions is to set yourself up for a fall or to have pretensions. So there is an underlying fatalism. ‘People don’t want to take the risk of a new job or a venture because they know in their hearts that they will probably fail.’

This, in turn, creates a strong tendency to live in the moment. Saving or preparing for the future is seen as pointless. There is a high premium on entertainment, with little sense of deferred gratification.

7. Relational assets

Traditionally, within mining communities, if a husband died, colleagues and neighbourhoods would take up a collection for the widow, often raising large sums of money. This social solidarity was evident during the miners’ strike of the 1980s. Now, however, working-class institutions, like trade unions and working men’s clubs, are in decline.

Yet social solidarity persists at a personal level. There is almost an unwritten contract that you share what you have with friends. Human assets matter more than financial assets. Friends help friends. ‘There’s a close bond on housing schemes,’ says Mez McConnell. ‘[Friends are] there for the long term.’ Ruby Payne says,

One of the hidden rules of poverty is that any extra money is shared. Middle-class puts a great deal of emphasis on being self-sufficient. In poverty, the clear understanding is that one will never get ahead, so when extra money is available, it is either shared or immediately spent. There are always emergencies and needs; one might as well enjoy the moment. [A poor person with money] will share the money; she has no choice. If she does not, the next time she is in need, she will be left in the cold. It is the hidden rule of the support system. In poverty, people are possessions, and people can rely only on each other. It is absolutely imperative that the needs of an individual come first. After all, that is all you have – people.

Steve Casey from Speke in Liverpool says,

We thought we would create community. But the locals know more about community. Our youth work could not compete with the strength of community in the area. If someone owes their last £10 for rent, and a friend asks for £10, then they will give it to the friend. If people are under sanction at work for attendance, they would rather lose their job than miss a distant relative’s funeral.

8. Non-abstract, concrete thinking

Our education systems condition people to think in terms of abstract principles, axioms and sequences. But working-class people are likely to organize knowledge in more relational ways. It is all about making connections with existing learning. These individuals are interested in what works – in the practical and immediate. For example, they are less likely to contribute to prayer meetings when the call to pray is general, but they will happily pray for specific requests. This does not mean they are illogical, but rather that their logic is expressed in concrete terms. They are more likely to express thought in pictures and stories.

Such people typically learn more through kinesthetic models, that is, learning by doing rather than by listening. They learn best when their learning builds upon prior learning, when they are able to contribute their own existing knowledge, and when they can connect what they are learning to that existing knowledge. They learn with rather than from people. The opinion of friends matters more than the opinion of ‘authorities’. They find out information by asking someone rather than looking it up in a book. Many have been disenfranchised by formal education. This means that an interactive Bible study with a focus on analysing the text can easily feel like an English comprehension exercise. So such people will often prefer sermons to Bible studies.

9. Non-diarized, relational lifestyles

The working class generally live in the ‘now’. They do not make appointments or feel any great obligation to keep appointments. The currency of the poor is rela...