![]()

1

Graphic History

This book is inspired by history, but not limited by it.

– Epigraph, Sarnath Banerjee’s The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers (2007)

In this chapter I focus on what is perhaps the most persistent theme in graphic narrative studies: its representation of History.1 Ever since Art Spiegelman’s genre-defying and field-defining Maus (1986, 1991) the graphic narrative has been the subject of discussion for its ability, or lack of it, to deal with History. I take my cue for reading the graphic narrative’s contribution to not just historical representation but the debates about how the medium can call attention to the problem of such representation from Hillary Chute writing, expectedly, on Maus:

The form of Maus, however, is essential to how it represents history. Indeed, Maus’s contribution to thinking about the ‘crisis in representation’, I will argue, is precisely in how it proposes that the medium of comics can approach and express serious, even devastating, histories.

(2006: 200)

My contention, in line with Chute’s, is that the graphic narrative’s representation of history must be read not just in terms of themes but also in terms of the form. Due to this dual attention, mandated I would say by the medium, this present chapter, like the rest of the book, constantly oscillates between and is organized around the technicalities of form and the content. The grammar of the text is integral to its theme and politics, and by shifting back and forth between the two I hope to highlight the constituents of the critical literacy the texts demand of the reader. In the graphic novel it is the contest, conflict and conflation of visual and verbal texts that generate critical literacy, even as these add, like in any literary text, the alternate voices, the metaphors and the subplots.

Further, I argue that the visual dimension of the graphic novel contributes substantially not only to our understanding of history but also to a larger question of how history can be represented. That is, it is within the graphic narrative medium with its potent mix of the visual and the verbal that we are made aware of the many loopholes, storylines, black holes, dead ends and labyrinths of history. We are made aware that what is (re)presented to us in the panels is often the marginalia of history, the outsiders, visitors and witnesses alongside the main protagonists. Finally, I also propose that graphic narratives such as the ones this chapter studies might be read not as mere comic books but as oral histories because they ‘struggle to represent, in pictures and in writing, spoken memories’ (Staub 1995: 34). They are ‘narratives that rely on the immediacy and authority of oral encounters with members of persecuted and oppressed groups’ (Staub 1995: 34). In many cases in the works I study here the speaker-narrator is telling us a story he or she has heard from a member of the family or community. What constitutes the text of the graphic narrative is a re-telling of this (hi)story.

In a later chapter (Five) I shall return to the graphic novel’s obsession with History but for a different purpose. In that chapter I shall examine several of these texts, and others, for the ways in which they recuperate another kind of history, of the repressed and the unsaid. This organization, where the chapters ostensibly dealing with the same theme, of History, in the graphic novel are separated by a third, is intended to draw attention to the reworking of History in more radical and social-critical ways in some of the texts.

Humanizing history

Spencer Clark argues that history gets humanized in graphic novels when we see the impact events have on the lives of people and their agency (2013: 498). This process of graphic humanization of history, as we can think of it, is achieved through specific modes of depicting agency. The graphic novel’s representation of humanization demands both, its attention to a textualization of historical processes and a visual schema by which we might locate the individual participant or spectator’s ‘view’ of this history as it unfolds. If the textual dimension delivers one aspect of the story, the expressions of characters and their location in the panels nudge us to paying attention to how individuals perceive and receive events as these happen. The former moves the plot of the literary text along. The latter generates the critical literacy by making us aware that history had witnesses who responded in different ways to the events, whose emotions writ large on their faces should convey to us the scope and nature of the events and thus alert us to the subjects of that history, the social and individual dimensions of the larger historical process.

Panels, positionality, agency

In the opening pages of ‘The Dark Armpits of History’, the second tale in Sarnath Banerjee’s The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers (hereafter BOWC), Banerjee chooses to focus on the ordinary English soldier in three out of the five panels. One shows an aristocratic/statesman-like figure, and one panel depicts the Reverend [James] Long (3). The tale itself opens with a page consisting of two large panels (instead of the usual six, common to comics), both depicting death in eighteenth-century Calcutta: one shows buzzards outside European mansions, and the second shows Christian gravestones in a burial ground (2). Then, before introducing the main theme – Philip Francis’s duel with Warren Hastings – Banerjee focuses on the ordinary life around 1780s Calcutta: the horse carriage with the driver in silhouette (4), the man watering the grounds (5). When the panels move on to depict the English duellers prior to battle – Philip Francis dressing for the event in a single panel covering the width of the page (5) – there is the punkahwallah, the valet and the man fetching tea. Francis’s famous duel with Warren Hastings has to wait for several pages to make its appearance. After the dinner scene with Madame Grand, we have a series of panels on the servants in a British household (8).

Arguably, throughout Banerjee’s frothy tale of colonial Calcutta, there is as much emphasis on the silent, unknown actors of the supposed main story as there is on the English protagonists. Are these marginal characters in any way a part of the historical narrative? Occupying as much space within the visual narrative of the graphic form, how do we ‘read’ them in the story? Writing about the historical agency of actors as presented in graphic novels Spencer Clark has argued that the manner in which an author positions the actors vis-á-vis the historical events helps us, the readers, determine the constraints placed on an actor’s agency (502–3). The speech of the actors and their nonverbal reactions help us understand this positionality (502). Ben Lander writing about history in comics says: ‘Comic histories tend to revel in the minute personal details of everyday life, which receive their due respect because of their personal or symbolic weight within the lives of the characters and the narrative that is being constructed’ (2005: 117).

What Banerjee’s narrative makes clear is that the history of British India, metonymically represented here in the form of colonial Calcutta, involved both British and native actors at every stage. Lurking in the corners of panels are Indian soldiers, servants, valets, stable boys, barbers, tailors and cooks.

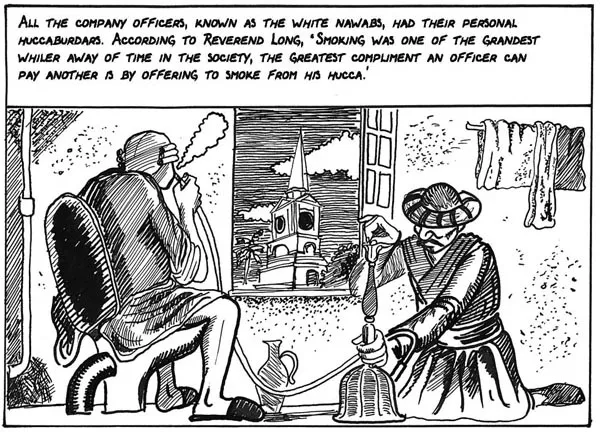

These are the minor characters in history, with no agency and who bow to the inevitability of history, but the graphic novel takes them and by forcing us to pay attention to them causes us to take a fresh look at history. Take a panel like the one on page 9 of Banerjee’s tale. It is a full-width panel showing an Englishman seated on a toilet puffing away at a hookah while gazing at the spire of a church outside. At his foot crouches an Indian servant working the mechanical contraption of the hookah. The text reads:

All the company officers, known as the white nawabs, had their personal huccaburdars. According to Reverend Long, ‘Smoking was one of the grandest whilers away of time in the society, the greatest compliment an officer can pay another is by offering to smoke from his hucca.’

I will have reasons to return to the nature of the commentary, dialogue and verbal texts in the graphic narratives but for now what I wish to underscore is the humanizing and concomitant dehumanizing aspects of colonial history. This is achieved by Banerjee’s brilliant deployment of space in the panel. The Englishman is seated on his toilet and close to him is the Indian servant working away at the hookah. The window is exactly in the middle dividing the space of the panel equally between the master and the servant. But it is also organized around the exposed situation of the Englishman whose gaze, when he is doing his business, is fixed firmly on the outer world, and the Indian servant’s on the hookah. What we see is ‘exposure’. Exposure here is defined as the making public of intimate moments, and, as Daniel Solove puts it ‘we are vulnerable and weak, such as when we are nude or going to the bathroom’ (2000). But the panel’s visual representation makes it clear that the native servant does not ‘see’ the Englishman in a state of exposure: the Englishman’s exposure, so to speak, is invisible in a wonderful arrangement of detail. The native is not entitled to look at the Englishman in this state of vulnerability; he must fix his eyes firmly on the hookah. Further, the Englishman himself does not notice the extremely awkward state of the crouching native servant, so close to the toilet bowl, because his own gaze is fixed on a distant object. The right to look, or to look away, is that of the Englishman alone, in whatever situation he might be in. What Banerjee alerts us to is this viciousness of racialized spatial arrangements as well as the agency of looking.

Figure 1.1 Sarnath Banerjee, The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers, New Delhi: Penguin, 2007. 9.

There are other examples of such careful positioning of actors that enable us to see the human side of history. In the case of ‘An Old Fable’ in This Side, That Side (TSTS) Tabish Khair and Priya Kurian depict the events leading up to the Partition of the Indian subcontinent. Using the fable of the two women, the infant and Solomon’s wisdom as the ur-narrative the panels depict two women crying over the rights to the baby lying in the middle. The panel is spread across two pages to show expanse, metonymically the expanse of the subcontinent under the shadow of a division. In the panel beneath this one, also spread across the two facing pages we see faceless crowds – presented in silhouette fashion – shouting, hands raised in demand or protest. Some are clearly Muslim men. The ‘King’ offers to hear their petition (19). On the next page the panel in the top half shows the men again, with speech bubbles all around, but with no text in these bubbles. Is it that the natives lack cogent speech that might be represented? Or is it that their speech is silenced? The narrative leaves it open for us to decide the point. The panel below shows the British officers ‘wri[ting] down the crowd’s complaints in convoluted petitions full of legalese’ (20). The expression on the faces of the English is smug. Later pages show transcripts of the petitions sent up (21). Then the King rules that the baby/country shall be divided ‘in the name of Reason, Science and, above all, Law and Order’ (24). References to mythic Islamic, Hindu and Christian tales of great ‘judges’ – Daniel, Suleiman and Harishchandra then occur (26–8) – thereby linking the English decision to native traditions of jurisprudence, as though there is a continuity. The Indians are portrayed in the panels as petitioners (20, 21), weeping (18–19, 25, 26) or angry (25). The only ones smiling through the tale are the English, and the smiles are clearly smug. When not smiling they are thoughtful, as in the portrait of the ‘wise’ King (23). The King looms over everybody else, towering into a full-page portrait (with Elizabeth II’s portrait in one corner, 22). This kind of portraiture where the King exceeds everybody else in size occurs thrice in the tale: when pondering what to do about the situation (22), when delivering his judgment (24) and when watching the women after the declaration (26). In this last portrait, he is cast as Rodin’s Thinker, the women have shrunk in size. But what is also important is that all personages occupy a black-and-white floor that resembles a chess board. The King is astride the chess board, to one side are the English, singing praises of his wisdom, to the other are the two weeping women. The King’s leg neatly divides the women spatially. Through this tale Khair and Kuriyan show how the natives were pawns on the chess board, their movements determined by the English players. The diminishing size of the actors brings home to us readers the relative insignificance of the natives in the shaping of their destiny at the Partition. While the story opens with crowds of natives there are only the two women and the divided baby at the end of the tale. The spatial arrangements – positionality – and the dialogue humanize the historical narrative because they foreground visually the human impact of English judgements, and the loss of agency of the native (human) actors in the events. The visual vocabulary is at the heart of the narrative’s theme, and we are made to see how this momentous event of 1947 was brought about. The spatial organization of panels and characters might be read as the metonymic equivalent of the stage of history itself.

There is one more point to be made about actors and agency in the graphic narrative. Narrating the story of Francis and Hastings is Abravanel Kabariti, a Sephardic Jew from Syria, who makes his appearance in various panels of Sarnath Banerjee’s The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers. At one moment he says: ‘I am the impartial timer, truly impartial because I have no fondness for either gentleman. Particularly not for Francis’ (Banerjee 2007: 17). Supposedly the person who is witness to the events being recorded, Abravanel foregrounds his own unreliability with these words. Banerjee therefore alerts us to the tension at the heart of the narrative: if Abravanel is unreliable and the Indian witnesses do not speak about what they saw, then how do we know what story to believe?

Other artists and storytellers of the graphic narrative seek to embody history differently, and call attention to this process of embodiment. This Side, That Side is printed on yellowish-tinted paper made to resemble parchment and old archival records. This engenders a critical literacy in the competent reader. The competent reader is made aware of the reconstruction of a historical event as being achieved through the examination of the archival footage. History rests on documentary and material evidence, often frayed and damaged, like old photographs, from the past. This meta-commentary on history-writing and the construction of collective and cultural memory in This Side, That Side is made possible by its brilliant deployment of a particular materiality – the parchment-type paper, the grainy texture – of form, its theme of documentary history, and its theme of the subjective, affective dimension of history. This last is, of course, made available again through documentary ‘evidence’ but evidence that captures emotions and expressions on the faces of the subjects of history. This Side, That Side, therefore, is at once an attempt to add to the literature of the Partition but also a text that cautions us, through its invitation to critical literacy about history-writing, against an easy assumption of access to History.

Nina Sabnani in ‘Know Directions Home?’ (TSTS) dispenses with the traditional panels. Narrating the story of the Indo-Pak war of 1972 and the forced displacement of people in the border area of Adigaam, Sabnani opts for dotted lines traversing the pages dividing and regrouping people into segments, populations and places. The pages are crowded with these figures representing people. It is also important that the voice that tells us the story opens with a ‘we’. This narrative then is interspersed with a woman speaking about herself and her family: ‘I don’t know why they were fighting …’ (100), ‘my husband …’ (103), and so on. There are also occasional individual voices, muted: ‘I don’t believe him’ or ‘Why is he talking so much?’ (105). When the tale ends, we have a name and full postal address of this woman (111). Sabnani might be offering an individual voice here, but what strikes us is the large number of people crowded into trucks, camps and tiny clearings in the forest. The absence of panels makes it impossible for us to read the story in any kind of temporal sequence although by virtue of our comics literacy we might read it top to bottom, left to right. But there is something else at work in her depiction of history.

Writing about abstract comics Andrei Molotiu has called ‘iconostasis’:

the perception of the layout of a comics page as a unified composition; perception which prompts us not so much to scan the comic from panel to panel in the accepted direction of reading but to take it at a glance, the way we take in an abstract painting.

(Cited in Tabulo 2014: 39)

This is different from the ‘sequential dynamism’ (of ‘normal’ comics), defined as

the formal visual energy, created by compositional and other elements internal to each panel and by the l...