eBook - ePub

Comparative Development Experiences of Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia

An Institutional Approach

Ernest Aryeetey, Machiko Nissanke, Machiko Nissanke

This is a test

Share book

- 492 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Comparative Development Experiences of Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia

An Institutional Approach

Ernest Aryeetey, Machiko Nissanke, Machiko Nissanke

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Title first publishedin 2003. This comprehensive book focuses on the prevailing conditions in Asia and Africa under various macroeconomic and sectoral themes in order to provide in depth explanations for the divergent development experiences of the two regions. Seeking to go further than the simple comparison of policies, the book carefully examines the institutional context for policy implementation within which growth and development have proceeded in the regions.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Comparative Development Experiences of Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Comparative Development Experiences of Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia by Ernest Aryeetey, Machiko Nissanke, Machiko Nissanke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Comparative Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part One

The Context

Chapter 1

Introduction: Comparative Development Experiences in Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia

Ernest Aryeetey and Machiko Nissanke

Before the Asian crisis of 1997/98, it was commonplace to juxtapose the dismal growth performance of the sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) economies against the rapid and sustained growth record of the East Asian economies, as the growth performances of the two regions began to diverge markedly in the 1970s. The East Asian development experiences were popularly presented to policy makers in Africa as an attractive example to draw lessons from. Indeed, many of the East Asian economies managed not only to register 'admirable' growth rates but also to accomplish relatively equitable income distribution with dynamically evolving changes in socioeconomic structures. The sharp contrast in economic performance of the two regions prompted the examination of factors and conditions that gave rise to the diverse outcomes, in particular because both regions had been subject to the same turbulent global environment.

In their early attempts, mainstream economists attributed the divergence in economic performances between the two regions almost exclusively to policy differences, especially the difference in policies for international trade and investment. It is true that there has been a clear disparity in the degree of integration into the global economy between the two regions. Aggressively following an outward-oriented development strategy, most East Asian economies not only accelerated the process of integration into the world economy but also upgraded their linkages in the years of their rapid economic growth. In contrast, the majority of SSA countries failed to take advantage of the opportunities provided by the increasing international economic interactions. In the 1970s and 1980s, instead of becoming more integrated into the world economy, they were largely marginalized and experienced slow growth and stagnation. With growing recognition of their disadvantageous positions, over the past decade SSA counties have increasingly searched for ways to accelerate their participation in the world economy.

Interestingly, the East Asian crisis erupted in the wake of this gradual embrace of globalization by African countries. The crisis, which started as a financial crisis arising primarily as financial excess, not a crisis of fundamentals. clearly exposed the severe difficulties in managing national economies in highly regionally integrated and globalizing environments. The event has helped us to raise a critical question for sub-Saharan Africa: how to manage the process of strategic integration into the global economy. As Senbet (1998) notes, the lessons from the Asian crisis, if drawn correctly, can help SSA countries to draw a strategy towards sustainable globalization.

The Genesis of This Collection

The Asian Crisis of 1997/98 radically changed perceptions and assessments of the East Asian economies, held popularly as the 'Miracle' story until the very onset of the crisis. As the crisis fast unfolded into a deeper general economic crisis of the whole region through the contagion effects in 1998, some commentators started forcefully arguing that the Asian Crisis was specific to the East Asian model due to 'crony capitalism', riddled by insider dealings, corruption and non-transparent corporate governance. The region's economic policies, which were previously regarded as a key ingredient in creating the miracle, were suddenly written off as a 'curse' for engendering the disaster.

In our view, these simplistic interpretations of the causes of either the miracle or the crisis only obscure a much needed realistic understanding of the conditions and factors that could explain the very different growth and development experiences of SSA and East Asia in the last four decades. Such naive assessments of the complex process of economic development cannot provide a satisfactory answer to the equally important question of why some East Asian economies have subsequently managed to engineer a rather quick turn-around from the crisis, compared with the historical experiences of other regions.

In a longer historical perspective, we suggest that there is no neat dichotomy between the broad policy frameworks adopted in the two regions alongside the well-established and clear divergence in outcomes. There have been, instead, some similarities in policy frameworks for significant periods, but varied in terms of implementation environments and in terms of sectors where some policies were targeted. By the same token, different countries in the two regions have adopted approaches that do not necessarily fit into a generalizable framework. Hence, it is necessary to go well beyond simple comparisons of policies at rather superficial levels and examine carefully the institutional implementation context within which growth and development have proceeded in the two regions.

In the past, we have often encountered casual remarks in which the experiences of the two regions are contrasted. This book intends to make amends for this by examining the processes that underlie each region's experiences. While we are not in a position to provide a comprehensive comparison of Africa and East Asia, we try here to present both African and Asian perspectives on what transpired in the two regions in specific areas, comparing policies, institutions and outcomes.

Specifically, this volume intends to bridge the knowledge gap that has arisen because researchers in the two regions actually know relatively little about each other's economies. Until now, African economists have had at best only a secondhand view of the economies of East and Southeast Asia, usually derived from the western scholarly literature. While these sources are useful, they do not sufficiently focus on the most relevant aspects of the Asian experience in terms of detailed policy design and implementation procedures. Similarly, Asian policy makers interested in making assistance to Africa more effective often have little knowledge of the economies of Africa and how best to situate the Asian experience in the African environment. Also, the recent negative conditions in such countries as Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Korea and even Japan need to be well understood and placed within the proper development context.

The book is a collection of the selected papers that were first presented at an international conference in Johannesburg in November 19971 in the background of the early phase of the Asian Crisis, The Conference was organized by the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) as the first programme workshop on the thematic topic of Comparative Institutional Analysis for its collaborative research programme, Comparative Development Experiences in Africa and Asia.

The programme was set up by AERC as an active research network to facilitate direct interactions and to conduct research on policy experiences among scholars and policy makers in Africa and Asia. The main objectives of this coll a borative research programme were to establish interactive channels for sustained conveyance and interchange of relevant experiences (and unfiltered lessons to be drawn) between African and Asian scholars and policy makers, and to provide a regular forum for discussing economic policies and observing directly how policies are related to economic institutions/agents in the two regions.

Many revisions to these papers were made in 1998-1999, as the Asian Crisis gathered its pace and evolved into a global financial crisis. Instead of revising the papers in tandem with fast evolving events, the authors were asked to focus on long-term development issues and the sustainability of economic structures and relationships. Hence, individual chapters of this volume discuss the crisis only in relation to the long-term growth and development. We discuss the extent to which the crisis affected a comparison with Africa in the paragraphs that follow.

Development Performance in Sub-Saharan Africa in a Comparative Perspective

Following the spurt of economic growth enjoyed in the initial post-independence years, real GDP growth rates in SSA countries steadily declined over the more recent decades.2 With growing populations, the economic growth performance in SSA, measured by per capita growth, has consistently lagged behind that of the rest of the world, particularly East Asia (Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1). Thus, amid the severe economic crises the region experienced in the 1980s, many countries initiated large-scale economic reforms within the context of donor-supported structural adjustment programmes. Some improvements, admittedly fragile, in macroeconomic balances in 'adjusting' countries have been recorded (World Bank, 1994). But, after 15 years of economy-wide reform efforts, the region's growth performance remains far too modest to lead the economies along a self-sustaining path of economic development and erode growing levels of poverty.

Table 1.1 Growth in GDP per capita, per cent per annum

| 1961–1972 | 1973–1980 | 1981–1990 | 1986–1996 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1.3 | 0.7 | –0.9 | –1.0 |

| East Asia | 7.0 | 7.1 | 9.4 | 7.2 |

| Southeast Asia | 3.2 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 6.6* |

| South Asia | 1.3 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.9 |

* Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand only for 1985–1995.

Source: World Bank, Economic and Social Data Base.

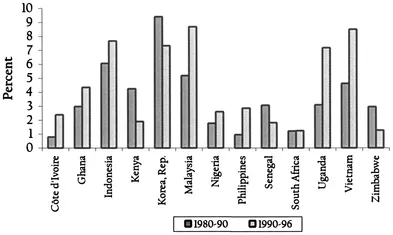

Figure 1.1 Average annual growth of GDP

Collier and Gunning (1997) note that during 1990-1994 the decline in African per capita GDP accelerated to 1.8 per cent per annum, 6.2 percentage points below the average rate attained by all low-income developing countries. Savings rates in most of sub-Saharan Africa remain at a depressed level (see Table 1.2). The low savings rates of these SSA countries suggest that investment and economic growth still depend heavily on foreign savings in the form of external finance. For many countries of the region, dependence on concessional aid flows for economic development has been high and rising. In the early 1990s, aid flows to Africa increased at 6 per cent per annum in real terms and aid constitutes about 9 per cent of African GNP, as compared with 2 per cent in South Asia (Collier, 1994). By 1994 aid had grown to 12.4 per cent of GDP. The aid dependence ratio is much higher for some countries. For example, gross concessional aid flows accounted for 49 per cent and 27 per cent of GDP in 1991 for Mozambique and Tanzania, respectively.

The differences in economic performance are probably most glaring with respect to participation in international trade and other external transactions. The ratio of world trade to GDP has doubled since the 1960s, with the ratio of merchandise exports to GDP rising from 11 per cent to 18 per cent and the share of primary products in total world trade being halved as that of manufactures rose.

Table 1.2 Comparative indicators on savings and investment

| Gross domestic investment as % of GDP | Gross domestic saving as % of GDP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1998 | 1980 | 1998 | |

| Low and middle income countries | 27 | 25 | 26 | 24 |

| East Asia & Pacific | 32 | 36 | 31 | 37 |

| Europe and Central Asia | - | 23 | - | 21 |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 24 | 22 | 22 | 20 |

| Middle East & N. Africa | 27 | - | 38 | - |

| South Asia | 21 | 22 | 15 | 17 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 24 | 18 | 26 | 15 |

Source: World Bank, World Development Report 1999/2000.

Among manufactured goods, there has been a decisive shift towards trade in intermediate goods and a major growth in intra-industry trade. About 20 per cent of the imports of many growing economies is for parts and components. It is estimated that close to half of the world trade in manufactures passes through multinational corporations. The trade in services has grown even faster as commercial service exports accounted for about 20 per cent of world trade in 1996. It is expected that the internationalization of these services will continue.

Africa has failed to be part of this dynamic growth of international trade in goods and services. The share of SSA in world trade has fallen from over 3 per cent in the 1960s to less than 2 per cent currently. Taking out South Africa, this share is only 1.2 per cent. There has been very little diversification. It is estimated that for SSA the erosion of the world trade share between 1970 and 1993 has meant a loss of $68 billion, or 21 per cent of GDP (World Bank, 1998). The poor integration of SSA economies into the global economy is reflected in Table 1.3, where we compare a number of SSA and East Asian economies. Trade as a percentage of GDP was as high as 70.2 per cent in Malaysia in 1996 and only 21.5 and 20.7 per cent in Nigeria and South Africa, respectively, two of SSA's largest economies.

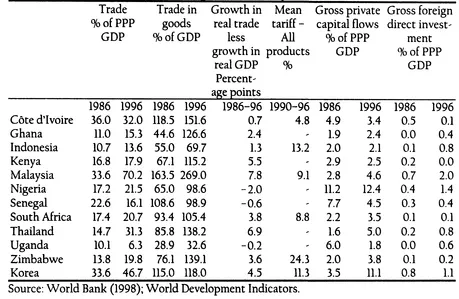

Table 1.3 Integration with the global economy

The growth in real trade as a percentage of GDP was fastest in Malaysia and Thailand. Only Kenya recorded a high growth rate among the SSA countries. For SSA, real trade as a share of GDP declined by an average 0.35 percentage points annually between 1980 and 1993, while it went up by 1.4 points for East Asia and the Pacific. However, export growth in East Asia began to slow markedly in the mid 1990s, and except in the Philippines, dropped sharply in 1996. The worst case was in Thailand where the nominal dollar value of exports actually fell. This has been attributed by Radelet and Sachs (1998) to over-valuation of exchange rates, the appreciation of the Japanese yen against the dollar after 1994, the competition effects of Mexico's participation in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the peso devaluation, and the world-wide glut in semi-conductor production. This deterioration of export performance was one of contributing factors in the Asian crisis, as discussed below.

During the early decades Africa achieved some notable improvements in development indicators, inc...