![]()

1

How Do We Need to Think, Act, and Meet Differently?

Times change, and we change with them too.

—Owen’s Epigrammata

THINKING DIFFERENTLY: PLANNED VERSUS OPERATIONAL CURRICULUM

Substantial amounts of time, money, and energy are spent to meet federal, state, and local curriculum mandates and directives. Guidelines, scope and sequences, frameworks, course descriptions, and measurement criteria are often developed to aid in defining students’ planned-learning expectations. While planning learning is needed and valid, a predicament occurs when data comparison begins. When assessment results and other forms of data can only be compared to planned-learning documentation, accuracy in accessing problems or solutions gives way to speculation or conjecture. If teachers are asked to evaluate why students underperformed on a state assessment, and there is no recorded documentation by each teacher of what was actually learned, the conclusions drawn will lack precision.

Two Perspectives

Curriculum mapping views curriculum from two perspectives. The first is the planned learning curriculum. Planned learning may or may not actually become reality. Therefore, a second view is necessary. The operational curriculum represents learning that truly happened.

A teacher’s operational curriculum documentation is called a Diary Map (Jacobs 1997). Planned learning curriculum is documented using a variety of map types, each with a unique purpose: (a) an individual teacher’s Projected Map, (b) a school site team’s Consensus Map, or (c) a districtwide Essential Map. A learning organization’s curriculum maps are accessed by using a Web-based mapping system. Each teacher and administrator has a personal log-in name and a password. Some systems provide guest passes that allow students, parents, and the community to view planned learning maps.

Jacobs (2006a) acknowledges that “curriculum mapping is formal work” (p. 115). Designing curriculum maps, and conducting formal mapping reviews (addressed in Chapter 7), takes a deep commitment of time and effort. If planning and implementation are well thought out, the endeavor will be a successful one. Jacobs (2004b) defines a mapping initiative’s success as having “two specific outcomes: measurable improvement in student performance in the targeted areas, and the institutionalization of mapping as a process for ongoing curriculum and assessment review” (p. 2).

A Student’s Journey

According to Marzano (2003), to master every discipline’s state standards, a student’s K–12 educational journey would take 23 academic school years. What he proved statistically, teachers know in reality. Teachers have to make decisions about what learning to omit. Unless teachers are diary mapping, a learning organization has no documentation of what each teacher has excluded.

Teachers have various reasons for omitting specific learning. What one teacher values, another may not. What one is comfortable teaching, another is not. What one deems necessary to study in depth, another does not. Environmental factors may also play a role in omission. An unexpected weather front that closes down a district for three weeks or the discovery of asbestos in a school’s ceilings that causes classes to be moved to another campus for two months will affect the outcomes of planned learning expectations.

While not intended to do so, a curriculum based solely on planned learning documentation may end up providing students with Swiss-cheese educations. Parents of triplets ask that Johnny, Jane, and Julissa be separated upon entering Kindergarten. If there is no collaborative, teacher-designed planned learning and no documentation of each teacher’s operational learning, there is a chance that the triplets will experience three different K–12 curricula. This is not to say that curriculum mapping demands the triplets’ teachers teach the same exact learning at the same exact time in the same exact way. It simply points out that students need teachers to document both the collaboratively planned learning and each individual teacher’s operational learning to best serve students and provide an equitable education for all.

10 Tenets of Curriculum Mapping

In any field of study, curriculum mapping included, there are principles that drive perception, communication, and how business is conducted. These principles, or tenets, provide consistency and flexibility in a learning organization’s actions (see Figure 1.1).

These tenets are paramount to how a learning organization may need to think differently than it has in the past. When a learning organization begins to think differently, it begins to act differently.

ACTING DIFFERENTLY: VERIFICATION VERSUS SPECULATION

Curriculum mapping is not meant to be an action that teachers simply go and do. This complex initiative cannot be grasped simply by attending an inservice or two. It takes instruction, exploration, experience, and adequate time before a learning organization’s members begin to act differently using documentation of what actually happened as well as what is planned.

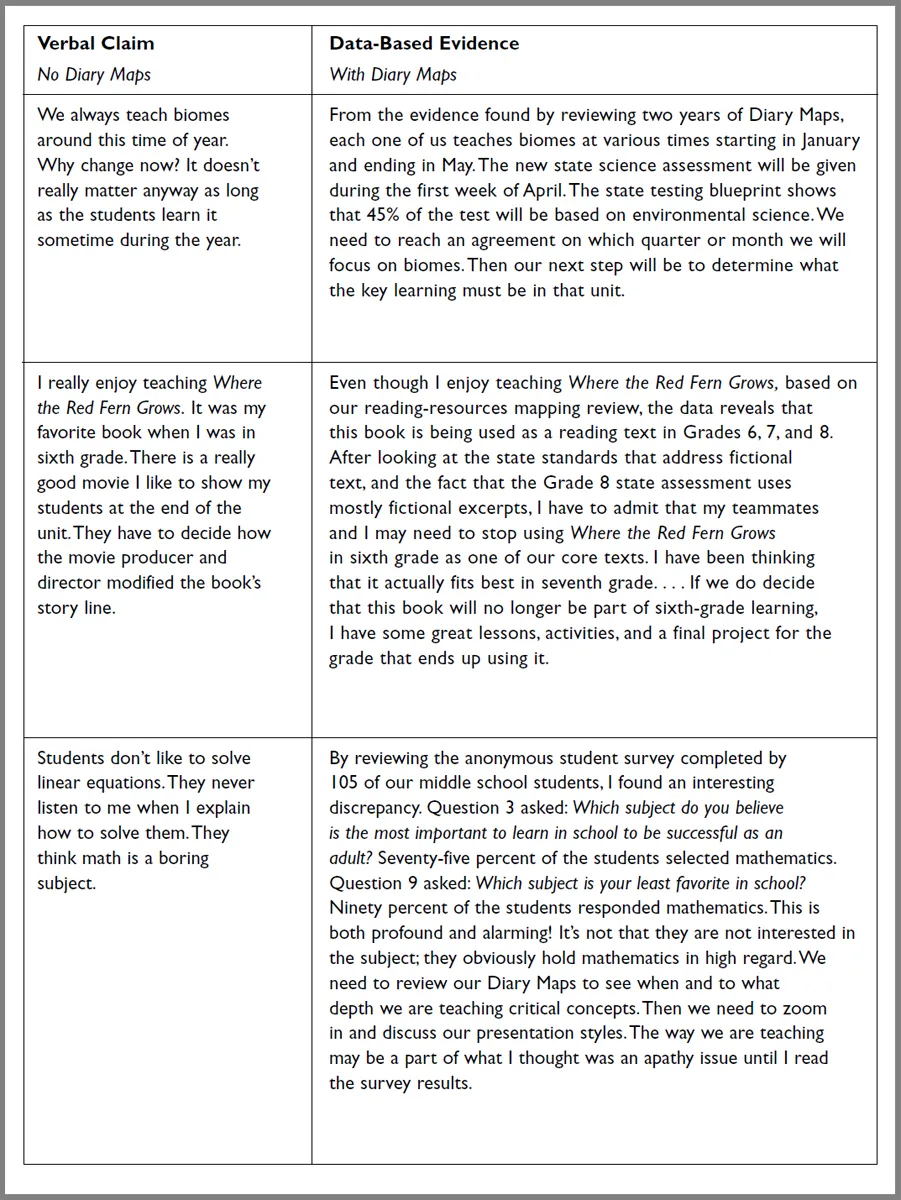

Evidence Versus Claim

To impact improved student learning, teachers and administrators must commit to using data-driven evidence rather than verbal claims. Diary Maps provide the evidence of each teacher’s operational learning. Figure 1.2 provides three examples of how this type of curriculum map can significantly impact curriculum decision making.

Data-Driven Collaborations and Decision Making

Curriculum maps are a form of data-based evidence that influences curricular dialogue and decision making. The sample on page 6 is just one example of how teachers may rethink or redesign a curriculum based on map evidence rather than on speculation.

Figure 1.1 10 Tenets of Curriculum Mapping

Figure 1.2 Verbal Claim Versus Data-Based Evidence

A Secondary Experience

A curriculum revelation occurred for one science teacher involved in the review. While reading his team’s Diary Maps before attending a small-group meeting, he discovered a course prerequisite anomaly. He taught an advanced placement (AP) science course. The Algebra I course had always been the prerequisite. Upon reading the maps he discovered that the content and skills learned in Algebra I are not sufficient. For years he’d been thinking that he was simply reteaching what students had forgotten. He now had evidence to the contrary. The students actually did not learn what was needed until Algebra II.

He shared his discovery with his small-group review team. Their conversation centered on the map-data evidence. The two departments met as a large group and eventually came to agreement on making an official change to the AP science course’s prerequisite requirements. Starting with the following school year, Algebra I and Algebra II would be the prerequisite courses.

This transformation instantly affected the science teacher’s class schedule because he had been teaching two AP science course periods. The science department collaboratively determined an appropriate replacement course.

When a learning organization starts to think differently, it will begin to act differently. To act differently, teachers must begin to meet differently.

MEETING DIFFERENTLY: A COLLEGIAL FORUM

A forum is defined as a public meeting place involving discussion among experts. Teachers are experts; they must be provided ample time and opportunities to discuss their questions of public interest—the students. Unfortunately, many schools and districts are constructed, both in physical layout and in time management, in such a way that meeting in horizontal (same grade level), vertical (series of grade levels), like (same discipline), or mixed (two or more disciplines) configurations on a regular basis is nonexistent or so infrequent that the meetings are ineffective. In fact, many learning organizations still function similarly to how schools and districts were designed to function in the 1890s (Jacobs 2006b).

For curriculum mapping to be an effective tool, meeting often with a preplanned focus and advanced preparation is imperative. While meeting face-to-face is important, if the ability to do so across grade levels or for mixed disciplines is not possible at the onset of a mapping initiative, the use of 21st-century technology, including an online mapping system, is indispensable.

Web-Based Mapping

Curriculum mapping advocates the use of a Web-based mapping system because it expedites curricular design and alignment (Gough 2003; Jacobs 2003a, 2003b, 2004a; Kallick and Wilson 2004; Udelhofen 2005). A mapping system provides instant access to the entire learning organization’s curriculum with the click of a mouse. Without having to travel to a particular campus to meet in person, a review team can enter the mapping system and instantaneously view what the planned or operational curriculum is on any campus.

A mapping system’s current and archived curriculum maps provide users with an interrelational database. Individual and collaborative map reviews are often conducted using a system’s search and report features. What previously may have taken hours to scan and search for by having to read a series of paper-document maps manually now literally takes seconds within a mapping system. A variety of comparison reports allow teachers to access map data from different school years, grade levels, and disciplines that significantly aid collaborations and decision making.

Throughout the remaining chapters, I refer to the necessity of using a mapping system to support the mapping process. Considerations regarding the purchase of a commercial system, or what must be considered for constructing a self-generated one, are addressed in Chapter 10.

Advanced Preparation

If a learning organization conducts rote meetings, oftentimes the wrong people are meeting at the wrong times for the wrong reasons (Jacobs 2006b). As a guest at many meetings, I have often observed that 5 to 10 minutes are lost while everyone gets settled. Another 5 to 10 minutes vanish while announcements that could be made via e-mail are shared. When the meeting finally turns to data review, teachers scramble to make sense of the presented data because they were not provided an opportunity to review the information prior to meeting. This approach is reactive and counterproductive (Costa and Kallick 2000).

Curriculum mapping asks for advanced personal preparation. This is a critical phase, or step, in the seven-step review process (Jacobs 1997). While Chapter 7 addresses each step in depth, it is important to note here that curriculum mapping asks teachers and administrators to individually review preselected data before meeting. Based on a predetermined focus, all in attendance will have taken personal notes as part of the preparation process (Jacobs 1997)....