eBook - ePub

The Lead Learner

Improving Clarity, Coherence, and Capacity for All

Michael McDowell

This is a test

Share book

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Lead Learner

Improving Clarity, Coherence, and Capacity for All

Michael McDowell

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

To make a lasting impact, redefine your leadership. Discover a new model of educational leadership, one that ensures growth for all students in both core academic content and 21st-century skills. With practical examples, stories from the field, and numerous activities and reflective questions, this insightful book takes you step-by-step through the work of the learning leader, helping you meet the unique learning needs of staff and students—and get the biggest impact from your own limited time. You’ll also find ways to:

- Ensure clarity in strategic planning

- Establish coherence throughout the system

- Enact system-wide capacity-building processes

- Craft your personal leadership skills

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Lead Learner an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Lead Learner by Michael McDowell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Leadership in Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Setting the Stage

When we study the biographies of our heroes, we learn that they spent years in preparation doing tiny, decent things before one historical moment propelled them to center stage. Moments, as if animate, use the prepared to tilt empires.—Danusha Veronica Goska (2004)

Are We as Leaders Ready to Prepare All Learners for the 21st Century?

Over the past decade, I have had the opportunity and privilege to wrestle with this question as I served as classroom teacher, principal, associate superintendent, and superintendent. I have also had the wonderful opportunity to work with and advise schools around the world to improve student learning. I have had the opportunity to engage with some of the most innovative schools and the most traditional schools, each with mixed results in terms of motivation, academic development, and engagement. My work has focused on ensuring that education leaders implement practices that are best for all kids.

Throughout this pursuit, I have observed how difficult it is for leaders to balance stakeholders’ demands that children on the one hand develop their reading, writing, and mathematical knowledge and skills and on the other hand their collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity skills.

Leaders have routinely asked me these two questions:

- How do we ensure that learners are prepared and competitive for the expectations of universities and colleges?

- How do we ensure that our learners are prepared for today and tomorrow’s society and workforce?

The tension in this balancing act is evident when educators walk over to me with copies of “innovation” books under one arm—for example:

- Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World (2012) by Tony Wagner

- World Class Learners: Educating Creative and Entrepreneurial Students (2012) by Yong Zhao

- Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All (2013) by Tom Kelley and David Kelley

- Hip Hop Genius: Remixing High School Education (2011) by San Seidel

and books advocating for traditional strategies under the other arm—such as:

- Visible Learning: Maximizing Impact on Learning for Teachers (2011) by John Hattie

- Why Don’t Students Like School? A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom (2009) by Daniel Willingham

- Embedded Formative Assessment: Practical Strategies and tools for K–12 Teachers (2011) by Dylan Wiliam

They ask, “How do I integrate the innovative learning of tomorrow with the traditional strategies that we know build the key knowledge and skills needed for today?” The daunting challenge of ensuring students have core academic knowledge and skills that are required in the information age while simultaneously developing the 21st-century skills and experiencing 21st-century learning environments is an ever-present reality educational leaders face today.

Often communities make a choice on whether to focus on a more “traditional” path of learning, arguing that core academic knowledge and skills should be the focus of schooling where other communities deem 21st-century learning to be the sine qua non of the schooling experience.

As we will see, such a dichotomy limits our decision-making, instigating a devastating impact on learning and learners. Leaders must transcend such a false choice and rather focus on the substantial progress of 20th- and 21st-century learning for all children.

The Driving Question: Are Our Decisions Leading the Learning?

The question we need to ask ourselves is, As leaders, how do we ensure that our decisions are substantially causing learning for all students in core academic knowledge and 21st-century skills? Over the past few years, I have seen more and more binary leadership approaches often framing schools and systems as needing to take an “innovative” path or a “traditional” path to moving student learning forward. This binary thinking became most vividly apparent to me when I viewed Most Likely to Succeed, a film focused on students who left traditional schooling environments for High Tech High—a project-based charter designed to prepare children for the 21st century (Whiteley, 2015). High Tech High is esteemed by many educators and has been cited in numerous articles and books including Tony Wagner’s bestseller Creating Innovators (2012). The argument made in the film is that student learning in the 21st century requires a fundamental redesign or reimagination of the educational model—no more desks, rows, silence, testing, and direct instruction from the all-knowing teacher. Instead, High Tech High offers students a high level of autonomy in their learning, a focus on curation and product development, and an expectation of collaboration and student-centered decision-making to solve rich, authentic tasks.

During the climax of the film, a mother is struggling with her decision to send her child to High Tech High because she worries that the academic foundations may be lacking. She is torn by a desire to ensure that her child receives an excellent foundation in academic skills while also desiring that her child benefit from the student choice, collaboration, and creativity that the school offers. As I watched her weigh the trade-offs of accepting the school’s approach to innovative methods over traditional practices, I wondered how such extremes have come to pass in various schools around the country. Subsequent scenes of the film show students building stages, performing plays, and constructing apparatuses while collaborating with others. Teachers intentionally shied away from directive feedback, instruction, or any recognizable educational intervention. It was evident that faculty strove not to engage in traditional reading, writing, and academic discourse and direct instruction and feedback. I left the theater wondering what would happen to the learners in High Tech High and as well as the learners in the traditional school depicted in the film. Moreover, I worried about the mother who struggled with having to make a choice between academic rigor and real-world relevance for her child. Are those really the options families must face for their children?

I believe that educators need not make a binary choice between traditional academic rigor and 21st-century skills. In this book I argue that school leaders must embrace both knowledge and skill sets and work to ensure that all of the students in their care receive the interventions necessary to progress toward traditional and innovative outcomes so that children will be prepared for tomorrow’s workforce and society. The argument in this book is that leaders transcend from creating innovative or traditional academic schools or school systems and focus on creating impactful systems that focus on ensuring students and staff are getting more than one year’s growth in one year’s time in core academic content and 21st-century skills.

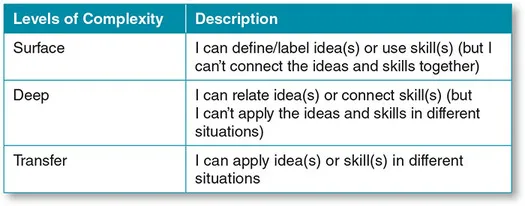

As we will see in future chapters, almost every action we take in a school works and the impact of such actions, particularly those that are instructional in nature, vary depending on students’ competency (Hattie, 2009; Hattie & Donoghue, 2016). For instance, Hattie and Donoghue (2016) illustrate that the impact specific learning strategies have on student learning is related to the level of complexity students are working toward (Figure 1.1). For instance, exploring errors and misconceptions have a far greater effect on learning when students already possess surface-level knowledge than when they are first learning the material (Hattie & Donoghue, 2016).

The idea of orienting strategies to levels of learning is, of course, not new as Marzano (2007) illustrated strategies to be used when students are interacting with new knowledge (i.e., surface), practicing and deepening understanding of new knowledge (i.e., deep), and generating and testing hypotheses (transfer). Hattie and Donoghue (2016) point to certain strategies, such as problem- and project-based learning, that are impactful when students already possess a comprehensive understanding of knowledge and skills (e.g., surface and deep knowledge), whereas the methodology is less than ideal when students are initially learning material. Beyond learning and instructional strategies, feedback strategies follow the same logic; aligning to levels of complexity enhances student learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

Figure 1.1 Levels of Complexity

The argument here is that our pursuit should be on ensuring learners are gaining more than one year in their learning with an equal intensity of basic knowledge (surface knowledge) and that of deeper learning (deep and transfer learning). Without this understanding, leaders will orient staff toward specific methods or a grandiose vision of creating “21st-century schools” or “academic schools,” rather than focusing on ensuring all students learn at high levels (i.e., surface, deep, and transfer) across a broad range of outcomes. Leaders will discard tried and true practices that have for centuries enabled students to learn how to multiply fractions, read an expository text, and write a poem in the pursuit of projects, virtual reality, and vodcasts (or the other way around). We must move away from the fixation of a school based on a philosophy of innovative or traditionalism and the mutual exclusivity of specific instructional methodologies over another and focus rather on how children learn and how children can take command of their learning across a broad range of outcomes and levels of complexity. We must lead by focusing on learning. Such a focus requires a few key leadership practices—tiny, decent things that are essential to learning for all. Leaders need to focus on how people learn and orient their decisions on ensuring people learn core academics and 21st-century learning deeply. As we will see, the focus of leaders and their corresponding actions have a dramatic impact on learning. We must think deeply about how students learn and from that understanding develop an approach to engaging with people as they learn, scaling our work, and making an impact on learning through our participation and promotion of learning. This requires a new type of educational leadership.

A New Leadership Focus

This book proposes leaders take on the role of a lead learner, focusing on cognitive (i.e., how people learn) and improvement science (i.e., how people get better at learning) and spending less time focusing on the traditional roles of educational leaders (see Figure 1.1). Unfortunately, contemporary educational leadership research shies away from the underpinning of student and staff learning and focuses squarely on creating the conditions for effective teacher practice (transformational leadership) or orienting leaders to focus on teachers’ actions to participate in specific instructional practices (instructional leadership) (see Figure 1.2). Though the research has shown that instructional leaders have a far greater effect on student learning than transformational leadership, these two styles are not mutually exclusive in practice (Hattie, 2009; Robinson, 2011). For example, in order to engage in classroom observations, educational leaders must also be effective at buffering external demands, setting direction, and being accessible to staff.

In systems that integrate 20th- and 21st-century learning, both instructional and transformation leadership are necessary. Leaders must utilize a wide range of leadership strategies at their disposal to meet the learning demands of students and staff. As will be shown, the transformational demands of the 21st century are easily embraced and scaled whereas the attributes of the instructional leader of the 20th century are less popular but essential to student learning.

Figure 1.2 ...