![]()

1 The bassoon

The early history of the bassoon, like that of most woodwind instruments, is obscure, so the evolution and development of the instrument has to be looked at fairly broadly. The bassoon, by the nature of its sturdy construction, had a better chance of survival than a flute. Because reeds and crooks are the most fragile part of the instrument, examples of these from the eighteenth century and before are extremely rare. Surviving instruments are rarely dated and only represent a very small part of the original picture. Iconography, while helping to fill some gaps in our knowledge of the bassoon, also leaves us with questions which are difficult to answer, especially in the case of inaccurate drawings.

The history of the bassoon is further complicated by the different names which were applied to the same instrument. This inconsistent terminology does not help research and care must be taken to ascertain which type of instrument is being described. Broadly speaking, the bassoon is part of a family of instruments originating in the first part of the sixteenth century, the two main features of which are a double reed and a long tube that doubles back on itself. Of this family, the curtal (chorist-fagott or dulcian) and bassoon (fagott, basson or faggotto) form the main branches.

The name curtal finds its root in the Latin curtus, meaning short; an allusion to the shortening of the instrument by the doubling back of its tubes. Its other name, dulcian, derives from the Latin dulc meaning sweet, presumably referring to the instrument’s tonal contrast to the brash shawms in use at the time. The German name, chorist-fagott, refers to the use of the instrument in providing a strong bass accompaniment for choirs.

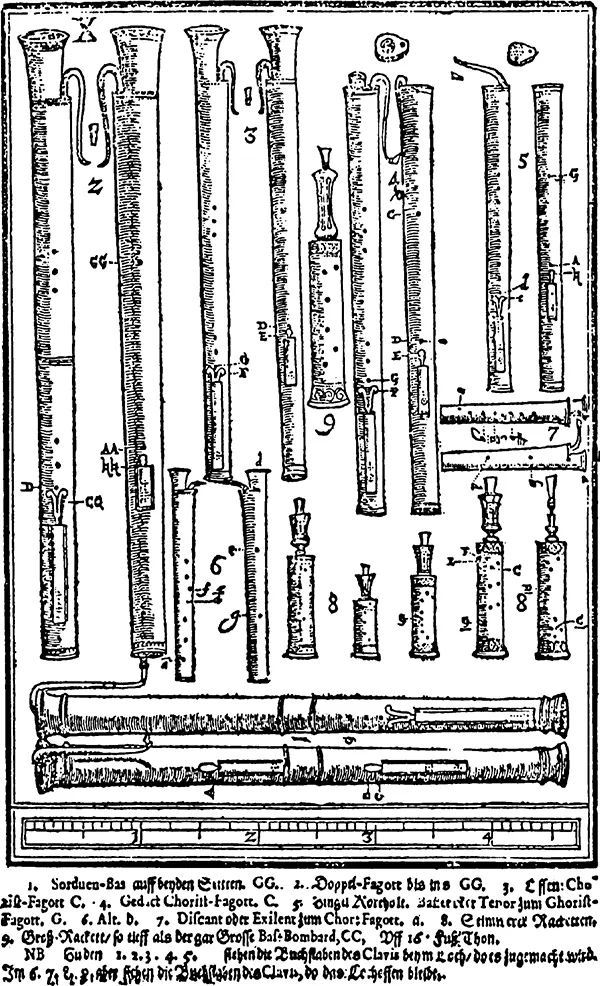

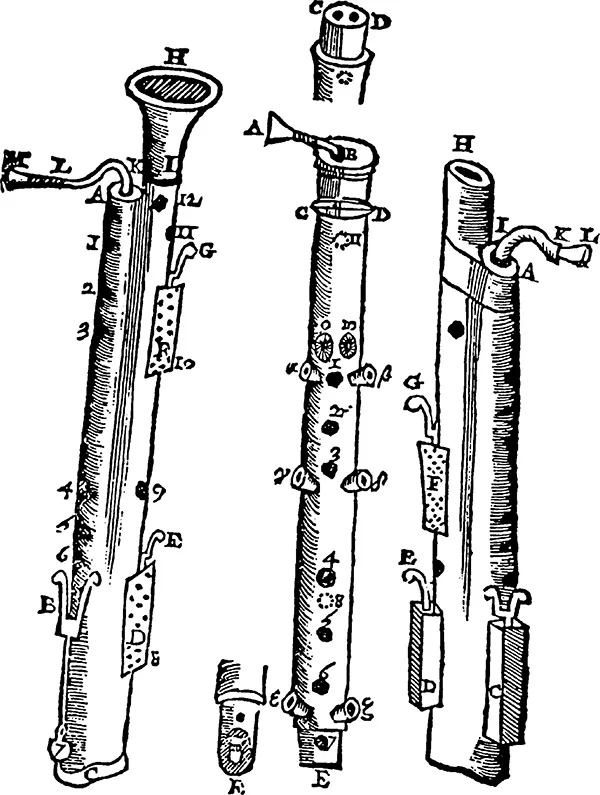

It is not clear exactly when or where the curtal was invented, one of the problems being the above-mentioned diversity of names. Most of our knowledge of the existence of curtals comes from court inventories which list, in various localities, instruments called fagotto, dulzin and curtall, to give but a few of the numerous nomenclatures. Two important sources are Praetorius and Mersenne. Michael Praetorius (1571-1621) in his De Organographia of 1619 makes no mention of a jointed bassoon, only referring to various sizes of ‘fagot’ of single-piece construction. In such a comprehensive survey of instruments this would have been a serious omission had a jointed bassoon been in existence. In 1636 Marin Mersenne (1588-1648) describes various types of ‘Bassons, Fagots’ in his Harmonie Universelle, clearly referring to members of the curtal family. He does make a distinction between ‘bassons’ and ‘fagots’, the ‘bassons’ being one-piece instruments and the ‘fagots’ being in two pieces, resembling a bundle of wood. The illustrations in Praetorius (see Figure 1) are clear and accurate in contrast to those in Mersenne (see Figure 2) which are crude and misleading.

The curtal is usually made from one piece of wood of oval cross-section with two tubes of conical bore, side by side and sealed at the bottom end with one or two plugs so as to form a continuous pipe (a crude precursor to the u-tube of the bassoon). At least one example has survived which has been made from two pieces of wood, bound with gold embossed leather (Frankfurt Museum). The widest end of the instrument was usually flared in the shape of a bell and was occasionally capped with a piece of perforated brass. Maple or pear wood were the most common types of wood used in their construction. Six finger holes, two thumb holes and two brass keys gave a range of two and a half octaves, from C to g. The two brass keys (F and D1) were encased in perforated brass boxes to protect them from damage and catching on clothing. The F key on the curtal was of the swallow-tail type which enabled the instrument to be played either left hand uppermost or vice versa. This feature, which appeared on a number of other wind instruments of the period, also appeared on oboes and bassoons until well into the eighteenth century. Another more fundamental similarity between the curtal and the bassoon was the way in which the fingerholes were drilled at an oblique angle through the walls of the instrument into the bore. This was necessary to facilitate the ergonomic layout of the finger holes. Given the length of the bore, if the finger holes were drilled straight into it, they would be too far apart for the fingers to reach. The double reed was not dissimilar from a bassoon reed although Mersenne notes that the blades of the reed were sometimes mounted on a brass staple. It is interesting to note that modern bass curtal reeds made by the German maker Rheindhart suit many historical copies of bassoons. There were up to eight sizes of curtal although the bass curtal (chorist fagott, bass dulcian) was the most successful of the range. As Baines so rightly points out in his classic book on wind instruments, ‘The bassoon has never shone in small sizes’.1

It is clear that the curtal was in wide use as a bass woodwind instrument throughout Europe from the 1540s until the beginning of the eighteenth century. Not only did it serve as the bass for consorts and bands but, in the hands of a virtuoso, it was an astonishing solo instrument.

Bartolome de Selma e Salaverde was a Spanish Augustinian friar employed by the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria as a solo curtal player from 1628-30. His set of works entitled ‘Primo libro di canzoni, fantasie e correnti’ was published in Venice in 1638 and contains what is probably the first solo for curtal in the form of a virtuoso set of variations on a theme. The solo part unusually descends to B1 flat, which may indicate that it was intended for the Quartfagott which had G1 as its lowest note. The Venetian Giovanni Antonio Bertoli (dates unknown) published a set of nine sonatas for the curtal and basso continuo entitled ‘Compositioni Musicali di Gio. Antonio Bertoli fatte per sonare col fagotto solo’ (Venice 1645). These works are some of the earliest known purpose-written curtal sonatas and are extremely demanding. The composer claims in his preface to the sonatas that ‘they demand a technical facility previously unexploited’. In his ‘Sonate Sopra La Monica’ (1651), the Darmstadt dulcian virtuoso Philipp Böddecker (1615-83) wrote a difficult set of variations for the instrument accompanied by a basso continuo and violin which supplies the theme La Monica.

It is interesting that Venice was the location for the publication of two of these sets of compositions. It has been suggested by more than one source that the concertos ‘per il fagotto’ by the Venetian Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) were intended for the curtal. Of the 39 concertos (including two incomplete works) at least one (RV495) descends to B1 flat. The bottom note on the bass curtal is C and it is extremely difficult to fake B1 flat reliably by ‘lipping’ the note down. The bassoon of this period had B1 flat as its bottom note and it seems unlikely that Vivaldi would have written a note in a solo passage which either lay outside the range of an instrument or could not be obtained by a particular soloist. Vivaldi knew his wind instruments as well as his string instruments and he had at his disposal a musical laboratory in the form of the Ospedale della Pietà, where he had access not only to talented students but their virtuoso teachers. It is likely that the Ospedale, like most music schools of today, probably held on to obsolete instruments such as curtals for economic reasons.

There is, however, much conjecture on Vivaldi’s writing of notes which do not obviously fall within the accepted compass of an instrument. Where such a note is written in the tutti section, that is when the solo instrument is doubling the first violin, then haste in writing might be blamed. A soloist would have been expected to play an alternative note, or to transpose the passage to a suitable part of the instrument’s tessitura. When a note that is obviously outside an instrument’s accepted compass is used in a solo passage, then one can only speculate whether it is a mistake made by a composer who is in ignorance of the instrument’s compass, or that it has been written for a player who has a personal facility for playing that note. The upper limit of the curtal’s range is usually held to be g1, the same as that of the bassoon. Vivaldi’s bassoon concertos usually have g1 as their upper limit, however the concerto in F (RV487) rises to a1 in its first movement. Because it is a fast movement it is difficult for the soloist to play such a high note, and it could have been written in consultation with the intended player who may well have been able to obtain this note on his or her instrument. Despite the few examples of notes which fall outside the compass of both the curtal and the bassoon, Vivaldi’s bassoon concertos are playable on both instruments. However, Vivaldi was usually quite clear in his designation of specific instruments both in title and tessitura. He used the title ‘fagotto’ in other works where it is clear that the intended instrument was bassoon, for example in the concertos he wrote for the Dresden court orchestra where there was a well-established tradition of bassoon playing. Given that many of Vivaldi’s bassoon concertos are the product of his later years it is reasonable to assume that he intended them for the bassoon rather than the curtal.

The origin of the word fagott (italian faggotto) is truly speculative. The idea that it might be derived from the word ‘phagotum’ is plausible given the known facts about the instrument. The phagotum2 was a double cylindrical bored instrument, the bores being joined at one end. A single reed was mounted within each of these bores and the instrument was attached to a pair of hand bellows which provided the wind (stored in a reservoir bag) to sound the instrument. In effect the phagotum was a type of bagpipe. Its inventor, a priest by the name of Afranio degli Albonesi of Pavia, took for his starting point the piva, a bagpipe of Slavonic origin, which differs from most instruments of its family in having two chanters and no drones. The first recorded performance using the instrument was at Mantua in 1532 when Afranio played the instrument, which he was now calling fagotto, during a banquet held by the Duke of Ferrara. The Italian word ‘fagotto’ means bundle of sticks; clearly Afranio’s instrument reminded him of that image and the name followed. Whether the Latinized name ‘phagotum’ came before or after the rather fanciful name ‘fagotto’ seems irrelevant. The word fagotto, which would be applied to numerous bass wind, reed instruments whose doubled-back bores were joined at one end, had arrived.

The baroque bassoon is typically in six parts, namely the reed, the crook or bocal, the wing or tenor joint, the butt or boot, the bass or long joint and the bell. How this form of the instrument evolved is not clear. There is a curtal in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna which has been made in two parts. It is one of the larger members of the curtal family and descends in pitch to A1. The upper joint comprises the tenor and bass tubes which fit as one into the butt or boot joint. Another instrument in the same collection has been made in three parts, a wing or tenor joint, a butt or boot and a bass/bell joint. This instrument, although a bass curtal descending to C, is slightly longer in length than usual bass curtals. It is, of course, dangerous to try to establish a neat history of the development of the bassoon given the many missing links so prevalent before the middle of the seventeenth century, but it seems logical that the next stage would be the addition of the bell joint, thus suggesting the basis for a four-joint baroque bassoon which would take the lowest note of the curtal, C, to the Bib of the bassoon.

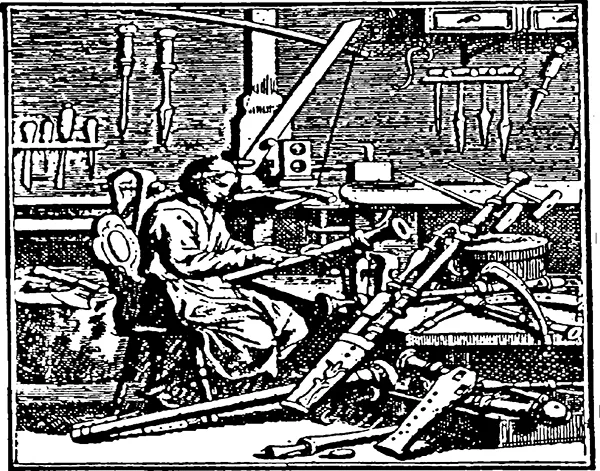

An engraving by Christoph Weigel dated 1698 shows an instrument maker in his workshop working on a curtal with a typical four-jointed baroque bassoon laid against his workbench (see Figure 3). The maker in the engraving is believed to be J.C. Denner of Nuremberg who died in 1707 and who made some of the last known curtals. The type of bassoon in the picture is certainly a Denner-type bassoon. If the bassoon was a development of the curtal then it would not make sense for a maker to continue the production of an earlier model. On the other hand the curtal in the picture could be old stock, or even an instrument in for repair. It must also be borne in mind that the curtal remained in use well after the invention of the bassoon. Whatever the true story behind the picture is, it is most likely that the bassoon’s invention came about from a need to produce a more sophisticated bass woodwind instrument.

Approaching the problem of dating the earliest bassoon from a different direction, it would seem possible that music written for the bassoon might provide some clues. Even when the date of a piece of music is known for certain, the problem of ambiguous terminology can create doubt as to the true identity of the designated instrument. Even examination of the range of a given part in a score can be misleading: for instance a part which descends to C only, does not necessarily mean that the part is for curtal.

The Hotteterre family of France3 is traditionally credited with the creation of the four-jointed bassoon, a form which has lasted as the basis for bassoons until the present day. The family originated from the Le Couture-Boussey district of Normandy where they were known as wood turners as early as the sixteenth century. Jean Hotteterre (c.1605-c.1690-2) had already established himself as a master wood turner in the town of Le Couture when he moved to Paris in 1632. Jean was mentioned by Pierre Borjon in his Traité de la musette (Lyons 1672) as ‘a unique man for the construction of all sorts of wooden instruments, of ivory and ebony, including musettes, flutes, flageolets, oboes, crumhorns, and perfect families of the same instruments’. Jean’s brother Nicolas (c.1637-94) also made the move to Paris where, like his brother, he set up a workshop (1657). He played the oboe, recorder and musette, entering the Grands Hautbois of Louis XIV in 1666, and the Chapelle Royal as a bassoonist two years later. A third brother, Jean le Jeune (died c.1669), played in the Grands Hautbois de la Grande Ecurie as a bassoonist and gambist. Whether Jean le Jeune’s bassoon was of the curtal variety or a true baroque bassoon is not known. Nicolas certainly made bassoons and it is commonly held that Jean was a great innovator in the construction of woodwind instruments. Independently or in collaboration the two brothers Jean and Nicolas may well have been the inventors of the four-jointed baroque bassoon. The influence of the Hotteterre family on woodwind instrument development and construction was monumental; it may be said that they created the blueprint for the modern woodwind instruments of today.

Instruments from France, probably made by members of the Hotteterre family, were reaching Germany during the 1680s and J.C. Denner (see above) was quick to assimilate the new technology into his own work. In England the influence of the Hotteterres may have been felt as early as 1673 or 1675. In 1675 Jacques Hotteterre sold a house in Le Couture to his brother Jean (1648-1732). The sale of the house may well have been the prelude to Jacques’ emigration to England. He was known to have been an oboist at the court of Charles II, returning to France in 1692.

Two years earl...