eBook - ePub

Explorers of Arabia

From the Renaissance to the End of the Victorian Era

- 310 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Explorers of Arabia

From the Renaissance to the End of the Victorian Era

About this book

Exploration usually demands the qualities of bravery, curiosity and organising ability. Arabia demanded more of the voyager: linguistic ability of a high order, scholarship and an imaginative temperament. It was also necessary to be able to pass as a native, if not of Arabia then of part of the Islamic world. The early explorers faced untold dan

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Gentleman of Rome

1503–1508

‘If any man shall demand of me the cause of my voyage, certainly I can show no better reason than the ardent desire of knowledge, which has moved many a man to see the world and the miracles of God therein.’

Varthema

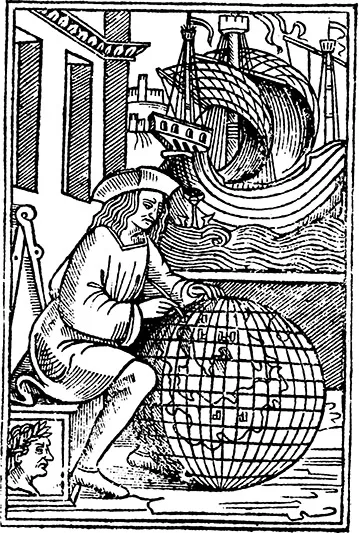

Title page of 1519 edition of Varthema’s Itinerary published in Milan

(courtesy British Library)

4 Varthema’s routes in Arabia, Persia, Ethiopia and India, 1503–08

It was no more than four years after the opening up of the sea route to India by Vasco de Gama that Lodovico Varthema left his native Italy for the East.

His journey in the earliest years of the sixteenth century took him to Egypt and the Levant, to Arabia and across the Red Sea to the land of Prester John, to Persia, Syria and the Indies. He joined the Portuguese army and he took military service, along with the delights and dangers of exploration, in his eager stride. He learned new languages as he went, adopted foreign customs with cosmopolitan ease, and embraced loyalties and religious faiths as readily as he cast them aside. He helped himself to the fruits and the livestock of his hosts, and not infrequently to their womenfolk, and he observed many strange and hitherto unrecorded sights, ‘keeping before me that the thing which a single eye-witness may set forth shall outweigh what ten men may declare on hearsay’.

There is no contemporary portrait, no extant description of Varthema. Yet from his own tale we have little difficulty in conjuring an image of the sixteenth-century pilgrim as he whoops his way through remote and unwelcoming lands, savouring their choicest commodities; sturdy of limb and swarthy of countenance, his manner composed of vagabond arrogance and easy charm, and guided by an irrepressible joie de vivre.

It is generally believed that he came from Bologna, but he preferred the designation ‘Gentleman of Rome’. There is no record of his birth or death. His own account of his journey and a few circumstantial details arc our only guide to the man and his achievement. ‘… what incommodities and troubles chanced me in these voyages, as hunger, thirst, cold, heat, wars, captivity, terrors and divers other dangers, I will declare by the way and in their due places’.

Thus he prefaced his own account of a long and eventful journey, cataloguing the tribulations that others who followed him to Arabia were to suffer in their turn, but never complaining.

Some time in 1503, he and his companions – he docs not tell us their names or how many they were-took their leave of Rome. They made for Venice, whence they sailed with prosperous winds to Alexandria. They did not delay long at the Egyptian port but sailed straight away up the Nile to Cairo.

Varthema travelled with a mind at once receptive and alive with preconception and imagery. ‘I marvelled more than I can say’, he remarked of Cairo when he first caught adistant glimpse of it. He was disappointed on closer inspection. The place was more thickly populated than Rome and full of Muhammadans and Mamelukes, ‘which are such Christians as have foresaken the faith to serve the Muhammadans and Turks’; a distinction which is neither accurate nor fair since the Circassian Muslims who were called by the Arabic name of mamluk or liberated slave, were reared in the faith.

The Italian left the swarming crowds of Cairo after a few days and took sail for Phoenicia and Syria, coming first to Beirut. He saw nothing of note in that town, remarking only that it was well victualled, but outside it he discovered the first of the landmarks of legend and biblical history that were to punctuate his journey-one of the several chapels of the Levant associated with St George, and the slaying of the dragon.

He was a curious explorer, imaginative and quick of wit, but vague as a chronicler. He seldom confides his goal, but we can be reasonably sure that Mecca was in his mind at this early stage of the journey. Its secrets, even its physical characteristics, had been mysteries to the Christian world for 900 years. Sketchy descriptions from the hands of Arab writers had found their way to the West but they gave no clear idea of the place or of the customs of worship which prevailed there. Varthema knew that he must master the Arab tongue if he was to pass among the people of the desert, much less gain access to their holy places, and he did not set out for Mecca directly.

Two days’ sailing from Beirut brought him to Syrian Tripoli where he noted only that the soil was very fertile. Tor the great traffic of merchandise, the place abounds incredibly with all things.’ Continuing northward, he and his companions reached Aleppo after another eight days. They looked in awe at the great staging-post of Syria, ‘this goodly city’, teeming with commerce and with goods brought in by caravans from all parts of Asia. Varthema went to the marketplaces where the merchants displayed their enticing wares and the caravans were loaded for their long journeys by way of Turkey, Arabia and Armenia, and inevitably he sampled the juicy fruits before turning south along the mountain road that led through Hama and Menin to Damascus. The Syrian capital was even more to his liking than Aleppo.

‘It is incredible, and passes all belief, how fair the city of Damascus is, and how fertile is its soil.’ Allured by the pleasures of the place, he was content to linger there while pilgrims in their thousands and even greater numbers of animals assembled for the trek to the holy cities of Madina and Mecca. Perhaps he parted from his fellow countrymen here, for there is no further mention of them, and he quickly decided to join the hajj caravan and thus make his way to the heart of Islam. He began to polish his Arabic among the Muhammadan inhabitants and Mameluke soldiery and to mix freely with both, as with the Christians of Damascus who lived, he said, ‘after the manner of the Greeks’. There was a great deal of sightseeing to be done and Varthema went about it with breathless energy and no little credulity. The great citadel of the Bibar amirs, the city’s main fortification since 1262, caused him to seek out the history of the place and its rulers and he was told a strange story of the gift of Damascus to a Florentine convert who saved the Amir Malik from the effects of poison.

Each day more ‘marvels’ came to light. The streets were lined with red and white roses, ‘the prettiest I have ever seen’, and with orange and lemon groves, pomegranates and sweet apples. The marketplaces were filled with flesh and corn and fruit and vegetables. But the city was not entirely above criticism. Varthema, who was more often governed by his appetite than by intellectual curiosity, thought the peaches and pears unsavoury.

A fine clear river, the Abana, ran through the place and everywhere fountains spilled cool water. There were many mosques, the finest of which, the great Omayyad masterpiece, he compared to St Peter’s at Rome. He invariably compared the features of the places he visited with Rome, never with Bologna, which suggests that he may have left his reputed birthplace in early youth. He observed that the mosque of the Omayyads ‘had no roof at its centre’ but that it was otherwise vaulted in the Western tradition, and that it was supposed to contain the body of the prophet Zacharia.

Wandering around Damascus he found several houses once inhabited by Christians, their woodwork finely carved and embossed, now in ruins. He inspected the tower within the city wall where St Paul was let down in a basket by his friends, to escape the hostile Jews, and outside the gates the place of Christ’s interrogatory ‘Saule, Saule, cui me persequeris?’ The excitement of a past unravelling before his eyes seemed to sharpen his pursuit of the present. He decided to take a closer look at the Mamelukes who swaggered in military manner through the streets of Damascus. ‘They live licenciously in the city’, he observed.

Yet they are very active and are brought up in learning and warlike discipline, until they come to great perfection. They receive a stipend of six pieces of gold a month, as well as meat and drink for themselves and servants and provision for their horses. They walk not singly but in twos or threes, for it is counted dishonourable for any of them to walk without company. They are valiant and if they chance to meet women (they tarry for them about such houses whither they know the women resort) licence is granted them to bring them into certain taverns, where they abuse them…. The women beautify and garnish themselves as much as any. They use silken appareil and cover them with cloth ofgosampine, in manner as fine as silk. Their shoes are red and purple. They garnish their heads with many jewels and earrings, and wear rings and bracelets. They marry as often as they like. When they are weary of their first marriage they go to the chief priest (who they call the Kadhy) and request him to divorce them. This they call Talacare. A like liberty is also granted to husbands. Some think Muhammadans had five or six wives together, which I have not observed. As far as I could perceive they had but two or three.

From his observation of the lives of these settled people at the edge of the desert, Varthema was able to learn a good deal that would be helpful when he travelled into Arabia. While he waited for the caravan to depart he kept up his observation of life in Damascus.

He watched the milk-sellers at work. They drove their goats to the houses, he noted, and milked them inside the living quarters. The goats’ ears were sometimes ‘a span long’, and they had many udders or paps and were very fruitful. He had the curious habit of enlarging the physical characteristics of the animals he met on his journey and of diminishing those of his human contacts. Even in describing the landscape he veered wildly between hyperbole and understatement, changing the size and shape of a mountain or a building to suit the mood of the moment.

The Italian cultivated the friendship of the despised Mamelukes. He may have had more of a taste for their ribaldry and merrymaking than he cared to admit. One in particular, the captain of the pilgrim caravan, the amiralhajj, became a close companion, although Varthema complains that he paid a great deal of money to be allowed to accompany him on the journey. Camels and pilgrims were gathered in numbers the like of which, if we are to believe the figures, have never since been approached on the hajj routes. Some 35,000 camels, 40,000 men and a goodly number of horses are said to have assembled for the journey. Varthema purchased a horse, dressed himself in Syrian clothing and adopted the name Yunis to see him through the pilgrimage. The caravan left Damascus on 8 April 1503 accompanied by a party of merchants.

Three days out, to the w-est of Jebel Hauran, they came to the small town of Muzairib where the merchants went about their business and the pilgrims replenished their provisions. Here they had their first sight of the badawin, members of a desert tribe said to be ruled by a shaikh called Zambei. He was apparently a man of great power, much feared by the sultans of the north. He had three brothers and four children and claimed 40,000 stallions, 10,000 mares and 4,000 camels. Such possessions would have represented riches indeed in the Arabia of the sixteenth century! ‘The country where he keeps these beasts is large’, says Varthema, ‘and his power is so great that he maintains a constant state of war with the Sultan of Babylon, the Governor of Damascus and the Prince of Jerusalem, all at once.’ At harvest time when the pickings were good this desert warrior gave himself up entirely to robbing, ‘deceiving his prey with great cunning’. His mares are of such swiftness that ‘they seem to fly rather than to run’.

Varthema was quick to observe the dress and fighting habits of the badu.

They ride on horses covered only with a loose cloth or mat, and wearing nothing but a petticoat. For weapon they use a long dart made of reed, of the length of ten or twelve cubites, tipped with iron after the manner ofjavelins and fringed with silk. They march in order and are despicable and of little stature, of colour between yellow and black, which some call olivastro. They have the voices of women and long black hair. They are of greater number than a man would believeandarecontinuallyat strife and war among themselves.

From the Italian’s description, the caravan seems to have been passing through the stony desert of the Hauran, with the Syrian mountains on their right, and the tribesmen of the Bani Sakhr to harry them as they went. It was a time of great disorder among the tribes of northern Arabia and Syria. Religious observance had fallen from favour among the desert chiefs and their people. Lawlessness was rife, pillaging and loose living were the fashion of the day.

However, the ‘despicable’ little men of the desert seem to have allowed the caravan to proceed unmolested. They had left Muzairib on 11 April, protected by their Mameluke guards. Each day they marched for twenty-two hours, a vast array of men and beasts surging wearily across the hot, uncomfortable desert. Mecca was a full forty days from Damascus. They were perhaps six or seven days closer by now, the pilgrims learning to sleep as they jogged and swayed on their camels, even riding on horseback with their eyes closed, but not for long; they had to keep watch for each other in case of attack by thieves. The caravan contained many poor pilgrims from distant lands; often such men and women were making the journey after saving for a lifetime. Sometimes they had money enough only for a one-way journey.

The caravan passed tents of the badawin, ‘black and made of wool and mostly filthy’. Otherwise they were alone on the well-trampled road to the cities of the Prophet. After their twenty-two hours’ stretch, they were allowed to rest for the remaining two hours of the day. The captain gave a trumpet call and commanded every man to remain on the spot assigned to him, ‘there to victual himself and his animals’. Then he gave a second blast on the trumpet and the replenished caravan moved off into the night. So they went on, day after day. Every eighth day the camels were rested while the men, or those of them fortunate enough to have two animals at their command, took to their horses. The camels were laden with incredible burdens, each carrying twice the normal load of a mule. They were allowed to drink but once in three days and were fed on great raw barley loaves, five at a time. Every eighth day again, the pilgrims dug for water in the sand. When they came to established wells on the route there was usually a squabble with Arabs who gathered around. But there was seldom bloodshed, which Varthema attributed to their ‘weak and feeble’ nature. It might also have been the case that the Arabs were unarmed at these watering-places. The Mamelukes, brought up in the military arts, were formidable fighting men. Varthema took great delight in telling tales of their exploits which often resembled medieval European joustings.

A favourite sport was to place an apple on the head of a servant, stand some twelve or fourteen paces away and swish a long lance over the head of the terrified victim until the fruit was struck. Fortunately the Mamelukes seldom missed. Their horsemanship was exemplary. They would take a fast mare with saddle and halter, undress it at full gallop and ride on with the saddle on their own heads. And they replaced it at full gallop. They were gymnastic soldiers, and not too scrupulous about whom they fought or with what inequality of arms. There had already been a few skirmishes and one of the Mamelukes had been killed in a battle with an Arab force said to number some 40,000. ‘No Arabs are to be compared to Mamelukes in strength or force of arms’, Varthema observed.

Twelve days out from Damascus they struck another valley. The Italian surmised that it was the site of Sodom and Gomorrah and he saw all around him ‘confirmation of holy scripture’. It was clear to see, he said, ‘how the people of the place were destroyed by a miracle’. He affirmed that there were three cities and still the earth seemed mixed with red wax, three or four yards deep. ‘It is easy to believe those men were infected with the most horrible vices, as the barren region testifies, utterly without water.’ Unfortunately, he was on the wrong side of the Dead Sea, a good many miles from the biblical scene he so vividly reconstructed.

In fact, the caravan was probably in the desolate region between Tabuk and Madain Saleh on the road from Maan by now, according to Varthema’s timetable. They seem to have been travelling a good way east of the road that became established in later centuries as the Darb al Hajj; a road which kept close to the hills along the Red Sea coastline for much of the way. Their present route was far from comfortable. Thirty or more of the company perished of thirst in the desert while others were buried in the soft sand and left to their fate ‘not yet fully dead’. The fact is stated without remorse or comment, an event like any other to be borne with fortitude on a journey of many hardships. Farther on they found a small mountain with water at its foot where they rested. Next day a force of Arabs estimated to be 24,000 strong came to ask payment for the water the pilgrims had taken. ‘We answered that we would pa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Gentleman of Rome

- 2 An Englishman at Mecca

- 3 The lone survivor

- 4 A Swiss in the Holy Cities

- 5 The Pilgrim

- 6 Through Central and Eastern Arabia

- 7 The Italian horse-coper

- 8 In Arabia Deserta

- 9 Journey to Hail

- Bibliography and Notes

- Diary of Major Journeys of Exploration in Arabia, AD from 1500

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Explorers of Arabia by Zahra Freeth,H.V.F. Winstone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.