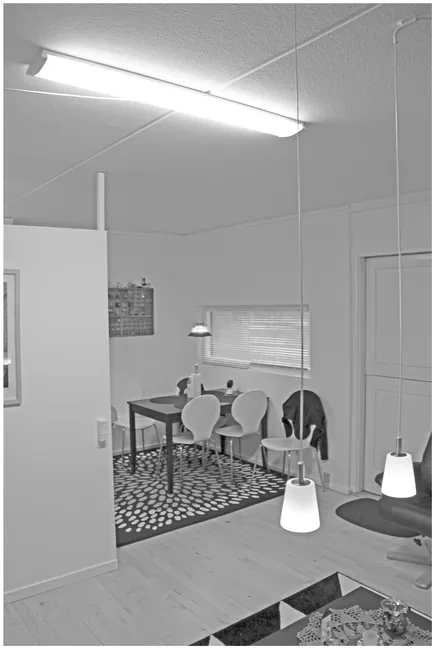

It is an autumn evening in Denmark, the sun is setting, and Cecilia is tidying her place. She makes sure there is no clutter, and that refreshments and sweets are ready for her friends, who are about to arrive. It is fairly common in Denmark to have friends visiting one’s home, compared to countries with warmer weather and a more vibrant restaurant, pub or café culture. Many people in Denmark make great effort to orchestrate a homely atmosphere that is ‘just right’ for a successful social gathering. Candy, cake, candlelight, music, alcohol, tea and coffee are material props that help to make people feel at ease; at least this is the idea. Cecilia, like other Danes, puts a lot of effort into arranging her home with design objects, and, if space allows, she creates different spaces within rooms for different situations: a reading spot; a relaxing sofa arrangement; a dinner section, etc. With such emphasis on atmosphere, materiality and presentation of self, the home in Denmark is an important place for social interaction and forging identity (Højer & Vacher 2009; Philipsen 2013; Winther 2005, 2006).

Cecilia is actually a little dissatisfied with the light from the two pendant lamps above the sofa. Not the lamp design as such, which she likes, but the light they produce; it is a minor irritation stemming from the fact that incandescent light bulbs were banned in 2012 in the European Union and replaced by energy- saving light bulbs. She feels these new bulbs are not as ‘good’ as the incandescent ones she used to have because they have a different shape:

the lamps hanging over the table are not made for those new [energy saving] round-topped bulbs; they were made for the [incandescent] flat-topped reflector bulbs. But those are not available anymore, and one has to be ‘a good girl’ and put the round-topped energy saving ones in instead. As you can tell, I am not satisfied at all. It’s all well and good with green energy and the environment and all that, if only they could keep their hands off my incandescent light bulbs.

One would perhaps not assume it at first sight, but a conflict is developing here in something as common as lighting one’s home. Staging the visual appearance of an evening in Cecilia’s home on the one hand exemplifies the common practice of orchestrating homely atmospheres and cosy gatherings through lighting. But it also shows the dissatisfaction with the minor visual differences energy- saving light bulbs have enforced.

While lighting may be about technical quality of light, measurements and energy efficiency, conversations with people easily turn to half an hour’s rumination on atmospheres, uncomfortable lighting in foreign countries, scary urban places, the bleak quality of the new energy- saving lighting, wrong bulb purchases and cosy (particle polluting) candle lights, which are called ‘living lights’ in Denmark. People may not have thought much about it until they are confronted by a different quality of illumination, or by an insistent anthropologist, but light is pivotal when shaping the atmosphere of a place. Informants are struck by the awkward sense of familiarity with what has been previously unnoticed, when I point out that in order to increase the flow of people on the Metro in Copenhagen bright light is used to help encourage movement along certain routes; or that there is a ‘colder light’ in the fish counter in the supermarket in order to make the fish look ‘fresher’; or that pinkish light is used to stop teenagers congregating in certain public places in England because it makes acne more apparent – similar to the well- known blue lighting in public toilets that conceals the veins of drug users. Such examples show that lighting technologies help constitute social life by conducting politics through (intangible) material means, increase consumption, and guide behaviour, most often at the margins of people’s attention. While people may more or less consciously orchestrate domestic lighting to fit activities and moods, public spaces are orchestrated visually for us at the edges of awareness to meet such political, economic or behavioural goals.

Light is so natural it is easy to forget how socially mediated it always is. A central analytical point in this book is that lighting is actually rarely about visibility. It may not even be so much about seeing in a strictly physiological sense. It is about seeing and sensing in a particular way. Lighting is an atmospheric element that tinges the material infrastructure and its affective presence, and thus also becomes appreciated in particular ways depending on context. Of course, when going up to a pitch-dark attic, lighting is about visibility, but how much light, the tolerance for glare and colour, and even what technology is available, is an outcome of social processes. Light is in essence thoroughly embedded in socio-material life, as much as it shapes the human body’s instrumental ability to see the surrounding world. As Marcel Mauss (1973) notably commented, one never simply looks, moves or senses. Rather, one learns how to through practices in specific contexts. Light and lighting, as something so commonly experienced and recognized, are imbued in cultural ideas and norms about intimacy, caring for each other, social gatherings, political power, class, sense of security, and traditions of what counts as visual comfort. And such sensory norms and connotations are learned rather than given.

To illustrate this point, let us return to Cecilia: Cecilia is visually impaired. She sheds light on the world to shape a visual comfort she has never herself fully experienced, employing sighted people’s vocabulary. She is not completely blind, though. While she has no sight, she does have some sense of light. She could find her way around the apartment in total darkness, but she got fed up of bumping into things, and found that sharp light offers a rough sense of orientation (hence the two luminous ceiling lamps were specifically selected for their light quality). At night, she also has a light turned on in the hallway between her bedroom and the toilet, so she can orient herself towards the door when waking up. But not just any sharp light will do. In some places, she could sense the difference in lighting quality between an incandescent and an energy- saving light bulb from the higher colour temperature; in other places, it was the spread of light the round- topped energy- saving light bulb gave, compared to the previous flat- topped incandescent reflector bulb where the lampshade orchestrated the light. As she said, ‘I cannot see it on the lamp, but I can see it on the light, it falls in a different way, it spreads a bit more.’

While it is commonly noted that people do not see light, but see in light (Ingold 2000: 265, 2011: 134; Merleau-Ponty 1964: 178), perhaps it is with Cecilia fruitful to rethink that famed dictum. As Gernot Böhme (2017: chapter 20) has rightly asked, is it not light we see when we are blinded by the light? Is it not light we see, when it falls through the windows, reflecting on surfaces of dust particles or smoke. We may of course know that it is actually dust particles that the light beams touch and we see; but cognitively knowing and sensing are not the same. Cecilia may of course also know that the light source creates a physiological response in her visually impaired eyes, and this is what she ‘sees’ rather than light ‘itself’. But perhaps, when we analyse how people sense the world around us – at least phenomenologically speaking – it is not fruitful to maintain such sharply delineated difference between objects, light source and reflecting objects, but instead approach a more vague, amalgamated, human embeddedness in illumination that rests on a long range of cultural logics and assumptions.

Cecilia’s domestic illumination illustrates something fascinating about the cultural logic informing the way people use light at home, not just in order to see something, but to see it in ‘the right way’, to make a place ‘feel right’ (cf. Love 2016; Pink et al. 2015). ‘Vision’ as such a continuous and mundane practice is performed with light and not just in light. Yet while a phenomenological account may highlight this embeddedness – rejecting an a priori distinction between subject and object – it often ignores how such sensuous encounter is culturally informed and trained. As Cristina Grasseni notes, ‘Vision, like the other senses, needs educating and training in a relationship of apprenticeship and within an ecology of practice’ (2004: 41). Small changes in lighting technology can in this sense mean a lot to people’s perception of visual comfort and norms. This book testifies to how the home is one site where such luminous training, perception and ideals take shape. Despite economic and ethical incentives to switch to energy- saving light bulbs, the background for this book is that many Danes have been reluctant to do so, hoarding incandescent bulbs, buying the less energy-efficient halogen bulbs, or using the new bulbs but complaining about poorer visual comfort. By being a location where people arrange themselves to feel at ease and well, the home here represents a ‘lumitopia’ (Edensor & Bille 2017) – a space in which an intensified attention to illumination is integral to the very particularity of the place in ways that makes sense – at least to them. This, of course, neither entails that people are always successful in orchestrating such spaces, or that the home is not also a stage for conflict and forging of moral subjects.

Time is working against the ethnographic descriptions presented here. Energy- saving light bulbs are constantly improving in quality, becoming more akin to incandescent lighting. Furthermore, many parts of the lighting industry are adopting the view that ‘good lighting’ is universal, circadian, and mimics the sun, and thus increasingly install dynamic lighting in offices and public institutions to produce better indoor environments. But what does that tell us about good domestic lighting and the sensory qualities related to it? It may be that light creates life, in contrast to darkness. But there is a wide spectrum between darkness and light, with natural and artificial light, and it is in the nuances of this spectrum, in the shadows, luminance, reflections and glare that people live. In Denmark, as shown with Cecilia, while light is life, it is in the moulded, dimmed light that people tend to live their lives. Despite rapid technological changes, light is embedded in atmospheric practices and cultural values, and these are only scarcely understood. This book is about such cultural notions and lighting practices. It illustrates the meaning light makes, the knowledge it takes, the politics it creates, and the concepts and practices lighting is shaped by, and conversely shapes.

Aims and scope

A large amount of research has studied how the physiological body and individual psychology reacts to various light, and its physical, spatial and environmental properties, mostly through positivist experiments and measurements (cf. Aries & Newsham 2008; Boyce 2014; Corrodi & Spechtenhauser 2008; Hopkinson 1964; Mills & Borg 1999). Such studies offer valuable insights that have shaped the way light is used and understood today, no doubt. But they are not sufficiently equipped to answer questions about the social life light partakes in shaping: the cultural logics and social practices embedded in the light shed on domestic and public spaces.

Take Peter Boyce’s influential book Human Factors in Lighting (2014) for instance: summarizing more than a century of knowledge on light, the book explores the relationship between light and humans. Substantial knowledge about light is presented, and yet there is an omission of any mention of social or cultural aspects of lighting – as if cultural traditions and social life are unknowable or secondary to the individual bodily response to light, rather than embedded in the very way people use, sense and make sense of light. What has emerged within lighting design and engineering is, as Boyce also laments (2017), a gap between ‘the art of light’ – dealing with the aesthetics and the end user, albeit at a more intuitive level – and ‘the science of light’ that deals with developing new technologies and understandings based on quantitative measures. The latter seems to reflect a scientism where the main universalistic assumption is that ‘good lighting’ resembles the sun, and consequently ‘daylight’ has been the outset for optimum colour rendering in light bulbs; lighting in this sense is understood in terms of its impact on a human body, with technical efficiency and quantitative measurements as an end- goal (Boyce 2017). This establishes a dehumanizing separation of the human body from the human person in what may be termed a ‘lumination gaze’ (cf. Foucault 1973). I argue that this version of ‘human- centred lighting’ is at risk of being an asocial perspective on both light and what it means to be human – even if this is not the intention.

In part, this omission is a result of the still relatively scarce literature on the social and cultural aspects as I highlight in Chapter 2. Broadly speaking, most research on the relationship between lighting and humans has been aimed at cause–effect research: if you lower light level to X, then Y will be the effect. Yet there are other kinds of research and knowledge, for instance one that aims at conceptual development for understanding what is going on and why. This book is meant as a contribution to a qualitative understanding of how humans adapt to, adopt, and live with light. It offers an exploration of the meanings, premises and uses of light in domestic lives. This is not intended to be an experiment with a ‘before and after’ to see the effect, but towards understanding what people do with lumination, and why. The premise of such a ‘social’ approach is that research on lighting practices and atmospheres needs to be situated, and understood, in the particular context, where concepts and insights can guide our understandings of other contexts.

An awareness of the sociality of light is particularly important when considering climate change. New technologies may be less polluting or afford a better quality of light, but if they do not fit into people’s cultural ideas and norms of how a place should feel, or even the relation between light and the objects it illuminates, their success may be limited. Beyond their technological efficiency, their capacity to offer change rests on their ability to make sense, and this sense- making, I argue, is also about shaping atmospheric spaces. Cecilia, a visually impaired person with strong sentiments about energy-sa ving light bulbs, illustrates this point, even if she did end up using them: the energy-saving light bulbs stood out as a separate entity of the home, rather than being integral to the domestic lumitopia. Part of the reluctance to accept the energy- saving light bulbs concerns, of course, their current quality, price and lack of standardization. But there is also a narrative that energy-saving light bulbs are of a lesser quality than incandescent ones, regardless of the validity of such claim.

The transition to energy- saving light bulbs has made the quality and quantity of light and lighting a hot topic in Denmark and elsewhere. Rather than a technical exploration, this book elucidates how quantity and quality of light unfolds through practices and atmospheres in domestic spaces in Denmark; that is, the cultural fit of a technological fix to energy consumption. The aim is to achieve a broader understanding of the role of light in social life through the power of example of a case study of lighting in Denmark. It aims to illustrate how ideas about the good life, home, morality, and identity are not only subjective mental capacities, but are achieved through technologies. Previous books have shown similar issues in the historical transition to electrical light (Barnaby 2016; Garnert 1993; Nye 1990; Schivelbusch 1988), yet still little is known about light as it is embedded in social life in contemporary society (but see Edensor 2017) and the cultural horizons it is part of (cf. Bille & Sørensen 2007; Daniels 2015; Kumar 2015; Wilhite et al. 1996; Winther 2008).

The central argument in this book is that, beyond offering visibility, lighting is a practice of attuning atmospheres for a variety of activities to take place in the home, such as social gatherings, cooking, relaxing, entertaining, cleaning, and feeling secure. While much research on light has focused on how much and what kind of light is appropriate for certain practices – such as reading or working more efficiently – I wish to refra...