![]()

1 Introduction

Margarita Zavadskaya and Holly Ann Garnett

Elections are designed to fulfill important democratic tasks: they give citizens the power to select their leaders, facilitate the transfer of power and hold politicians accountable for their decisions. However, this process can easily break down: incumbents manipulate electoral rules to their advantage, election day is wrought with vote-buying and ballot-box stuffing and ballots go missing during the count. All elections, whether in new democracies or jurisdictions that have held elections for decades, whether in long-standing democracies, strong authoritarian contexts or countries in the midst of regime transitions, are vulnerable to malpractice.

This volume considers how we judge the quality of elections across the variety of regime types that exist around the globe. It begins with a normative approach to electoral integrity, or an understanding that there exist norms and standards for elections that can be applied universally, regardless of regime type or cultural context (Norris 2014). However, this does not preclude the possibility that certain challenges to electoral integrity will be more frequent depending on the type of regime or its institutional strength, or that the variety of actors involved will have different levels of power and opportunity, or that the consequences of particular challenges will be different.

This volume argues that the diversity of challenges to electoral integrity stem, at least in part, from two key factors – the nature of a country’s political regime type and the state’s capacity to maintain its power across the country’s territory. It bridges the literature on electoral integrity with that of political regimes, by arguing that there are unique challenges to electoral integrity based on regime type and state capacity. The chapters in this volume explore this relationship according to three major themes: actors, strategies and consequences. First, while most literature on electoral integrity, particularly in non-democratic regimes, focuses on the role of incumbents in electoral manipulation, we suggest that a broader scope of actors, including foreign leaders, opposition groups, electoral administrators and even organised crime, need to be considered when studying electoral integrity. Second, the chapters in this volume consider how these actors respond to their contexts in their choices of strategies for electoral manipulation. Finally, while there is a well-developed literature about whether elections in non-democratic regimes will lead to democracy, there are other possible short- and long-term consequences of poor electoral integrity. In this volume, we look specifically at questions of political efficacy and turnout, the threat of electoral violence and protest, and finally, the possibility of regime change.

This volume expands our scholarly understanding of electoral integrity and political regime types by exploring the diversity of challenges to electoral integrity, the various actors involved in perpetrating electoral malpractice, the strategies they use, and the consequences that result. This introduction first summarises the major methods of evaluating electoral integrity in comparative perspective. It next considers the regime determinants of electoral integrity, namely regime type and regime strength, presenting a typology of the major challenges to electoral integrity based on these variables. It concludes by introducing the often-overlooked actors, strategies and consequences that will appear in this volume.

Understanding electoral integrity

Scholars and practitioners have long sought to make sense of the ways that elections can be threatened by finding methods of measuring the quality of elections. There are a number of approaches to judging the quality of elections around the globe (Birch 2011; Butler et al. 1981; Elklit and Reynolds 2005). Some approaches draw from democratic theory, asking whether elections are fulfilling their purposes as tools for citizen input to the government. Other approaches consider whether elections adhere to the national or regional laws that govern them. These legal approaches may, for example, determine whether only eligible citizens, according to national laws, are casting ballots, or consider whether campaign finance laws are respected. But while election laws provide clear rubrics by which to judge elections, this approach has a number of drawbacks as well. First, election laws will vary greatly by country, or even by jurisdiction within a country, making comparative research on the quality of elections quite difficult. Additionally, some election laws may be considered unfair, making it difficult to judge the quality of an election run according to these laws. For example, in some countries, only one party is permitted to participate in elections. These elections may be considered of good quality according to the laws that govern them, but they do not allow for a wide range of choices for the electorate. How, then, should we judge or compare elections, without a clear sense of which laws are fair?

In some instances, considering the cultural context in which the election is conducted is worthwhile. These sociological approaches may use mass surveys that ask citizens their own perceptions of the quality of an election (Elklit and Reynolds 2002). This approach allows scholars and practitioners to compare elections, without making assumptions about what types of laws and activities during an election are fair. However, this approach also has a number of drawbacks, particularly that the basis on which an individual might judge the elections will likely be dramatically different across contexts. There are a myriad of other factors, such as experience with elections, minority groups status or whether a voter’s preferred party won the election, that may influence their perceptions of electoral integrity (Howell and Just-wan 2013; Singh et al. 2012). Cross-national and cross-cultural comparisons then remain a challenge for scholars and practitioners.

This volume therefore employs a normative approach to studying electoral integrity, which forms much of the basis for current scholarship on the subject. This approach judges elections according to the norms and principles for elections that have been agreed upon by the international community. This approach is often linked to the term ‘electoral integrity’, popularised in recent years by Norris and her colleagues, and defined as the adherence to “international conventions and universal standards about elections reflecting global norms applying to all countries worldwide throughout the electoral cycle, including during the pre-electoral period, the campaign, on polling day, and its aftermath” (2014, p. 21). The specific principles, norms or standards that guide the conduct of these various stages of the electoral cycle can be drawn from international agreements or treaties, such as the United Nations International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights,1 or election-specific documents from organisations like the Organization for the Security and Cooperation of Europe2 or the Inter-Parliamentary Union.3 As such, electoral integrity is a concept that can be applied equally to all jurisdictions and contexts, regardless of location, culture or experience with elections and democracy.

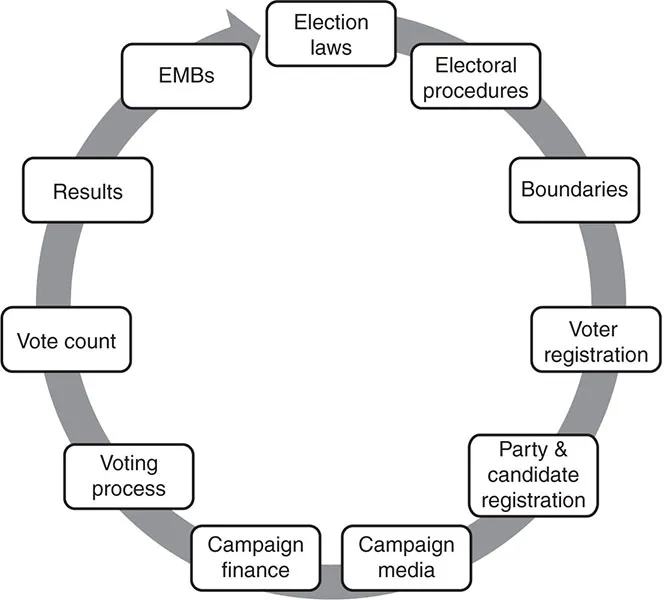

Additionally, according to this definition, elections are not just what happens on election day, but what occurs beforehand, when laws are enacted and election administrators plan and prepare for an election, and what occurs afterwards, when the final results are tabulated and announced, and candidates accept (or chose not to accept) the results. Scholars and practitioners often depict this as an electoral cycle of activities that begins anew after every election (Figure 1.1 ).

But when considering such a variety of activities and responsibilities that go into elections, there are also a plethora of ways that elections, throughout the electoral cycle, can fail. As such, several important works on electoral manipulation or malpractice have emerged in recent years on how elections may not only fail to achieve the international norms and standards mentioned earlier, but how actors may actively attempt to manipulate elections. Birch (2011), for example, presents three avenues for electoral malpractice, namely the manipulation of electoral institutions, or the legal framework by which elections are run, the manipulation of the vote choice, and finally the manipulation of election administration. Another seminal work on this topic, by Schedler (2002), presents a number of criteria for elections, following a ‘chain of democratic choice’, and outlines how an election may move beyond our democratic ideals to a means of authoritarian rule. This delicate tension between elections as deliberate democratic acts, while also susceptible to a great deal of manipulation, is particularly important when we look at the diversity of regimes that hold elections. We quickly discover that while elections in all countries, from autocracies to the most long-standing democracies, can be measured according to the same principles, according to normative definitions of electoral integrity, different regimes are susceptible to particular types of manipulation, particular actors that perpetrate them and particular consequences of poor electoral integrity.

Figure 1.1 The 11-step electoral cycle.

Regime types

In order to parse out these patterns in electoral integrity and regime types, it is important to draw on the wide body of literature that has classified and defined different types of political regimes over the past 30 years. In this volume, we look at the effects of the regime type, first, differentiating between democratic and authoritarian regimes, and, second, introducing differentiation within authoritarian regimes in particular.

Repeated attempts to make sense of the real-world variety of political regimes have generated a plethora of various typologies. Each typology draws on a unique definition of democracy, or highlights specific features of regimes that constitute necessary and sufficient conditions for a regime to qualify as a democracy (Coppedge 2012; Przeworski 2000). The most common typologies are based on a continuum on which all countries can be placed. Some examples of this include the scoring by Freedom House4 and Polity.5 Other conceptualisations suggest a dichotomy of regimes as either a democracy or dictatorship, and may further categorise these regimes into sub-types (Cheibub et al. 2010).

Both types of classification recognise that not all democracies nor all dictatorships are the same (Gandhi and Przeworski 2007). Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland emphasise that

after being treated as a residual category for much time – everything that democracy is not, dictatorships increasingly are recognised as a political regime encompassing different ways of organizing political life that have consequences for understanding policies, outcomes, and the stability of authoritarianism itself.

(2010, p. 83)

Elections in authoritarian regimes are not just window-dressing or simply an arena for rents distribution, but serve as forums for decreasing informational uncertainty, articulation of demands and co-option, when it is needed. Consequently, the differences between various institutional designs are not random, but vary systematically according to the needs of political incumbents in a regime.

But ongoing debates on classification and measurement of non-democratic regimes in particular make it challenging to agree on specific terminologies for non-democratic regime types. We often rely on the concepts of ‘competitive’ or ‘electoral authoritarianisms’, as special subcategories of authoritarian regimes where competitive elections constitute an important part of political life. This perspective implies the continuum of political regimes where ‘electoral’ or ‘competitive’ are placed somewhere in between genuine electoral democracies and blatant non-electoral or non-competitive autocracies. However, in order to account for the specific institutional traits within this pool of competitive or electoral authoritarian regimes, further typologies are required that treat types of political regimes as different categories or qualitative types, such as military, single-party, personalist or monarchic regimes, that are based on variable control of access to power (Geddes 1999), the method of removal from power (Cheibub et al. 2010; Gandhi and Przeworski 2007) or the characteristics of their inner sanctums.

In this volume, we rely on one of the most common distinctions between democratic and authoritarian regimes based on indices of democracies such as Polity and Freedom House (Diamond 2002; Hadenius and Teorell 2007; Howard and Roessler 2006). It is important to note that explaining the variance in electoral malpractice by regime type may run into a problem of endogeneity, since the difference in electoral integrity constitutes one of the definitional features of democracy. This is why the volume also focuses on the variance mainly within a non-democratic spectrum, thereby holding the type of political regime constant.

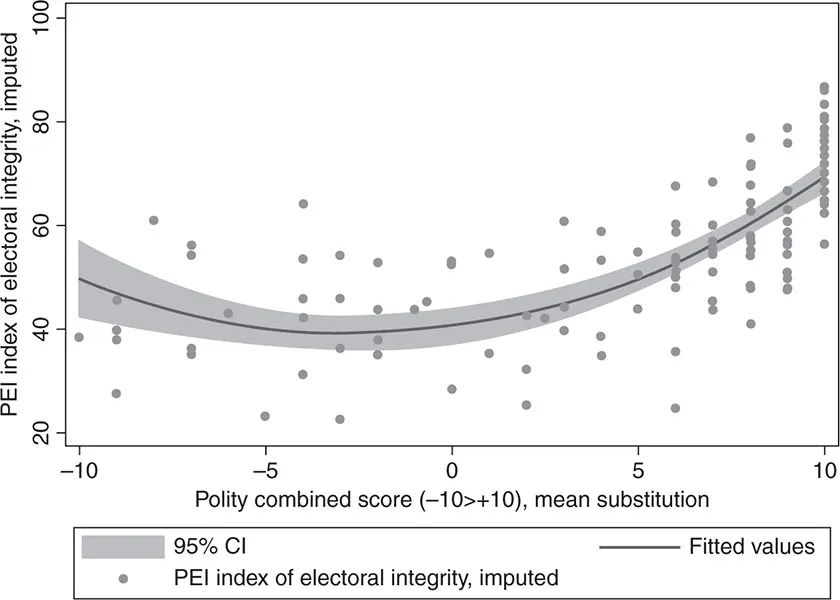

Figure 1.2 Perceived Electoral Integrity Index by type of political regime.

Turning to the impact of political regimes on electoral integrity, it is possible to consider how regime types are related to cross-national measures of electoral integrity. Looking at the distribution of perceived electoral integrity (expert assessments by the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity Index6) by the regime type (as measured by Polity), we observe a positive and somewhat curvilinear relationship. Figure 1.2 supports the conventional wisdom that more democratic regimes tend to score higher on electoral integrity (Norris et al. 2014). Many of the same characteristics that make a country democratic, including high levels of civil liberties, strong civil society organisations, an independent media and functioning governmental institutions will contribute to electoral integrity.

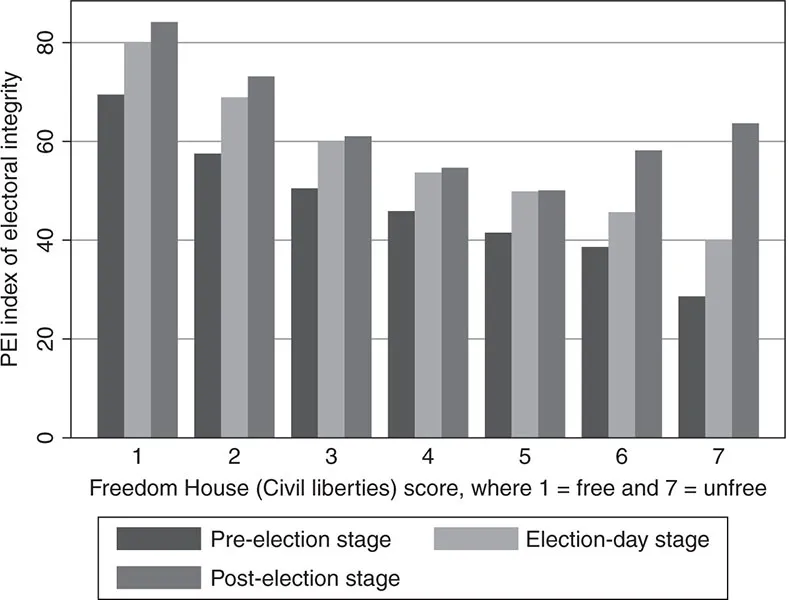

But the relationship between regime and electoral integrity is not linear: we observe considerable dispersion in the authoritarian part of the continuum, as the correlation nearly vanishes. Likewise, Figure 1.3 demonstrates how electoral integrity generally declines as a country’s civil liberties score by Freedom House decreases. Pre-election and election-day violations become more widespread, but the aspects related to the post-election stage – reactions to the official announcements of the results in forms of protests or disputes – seem to ‘improve’ in stable authoritarian regimes.

Figure 1.3 PEI Index disaggregated by election stage and regime type.

This relationship begs the question of why electoral integrity is not so simply ...