![]()

1 Introduction

Robert Clark

Critical commentary on Austen’s geographies began almost a century ago with a seminal essay by Sir Frank Mackinnon in which observed that Austen was the first British novelist to represent locations with geographical precision, a method that seemed to parallel her use of almanacs to ensure that her events fitted the chronology of the year in which they were set. Mackinnon writes

As she had an almanac for her dates, so, I have little doubt, Jane Austen used Paterson’s or Carey’s [sic] road books for the travels of her heroes and heroines …. Feigned places, however, are always, and in every way, fictitious. Attempts have been made to identify some of them with real places – e.g. Mansfield Park, or the Highbury of Emma. But they have been the guesses of inaccurate readers …. Jane Austen, I feel sure, never copied a character from a known person: I am sure she never delineated a known place under a fictitious name. But she probably knew the place she conceived as well as the character she created, and knew either as well as her familiar haunt, or her dearest friend—Highbury as well as Steventon, Elizabeth Bennet as well has her sister Cassandra.

(Mackinnon 1925, 184)

MacKinnon’s term “feigned places” nicely catches the quality of Austen’s imagined houses, towns and villages and was later adopted in the lists of “feigned place” appended to Chapman’s Oxford editions. The term, however, sits over a chasm which is hinted at when Mackinnon says Austen “probably knew the place she conceived as well as the character she created.” MacKinnon means Austen knew that just as her imagined characters can sometimes be traced to real people whose characteristics they share, so we often sense that her imaginary locations have real-world equivalents. In a published letter discussing Austen’s representations of place, R.W. Chapman observed that “the search for originals is not altogether idle. Jane Austen was exceptionally, and even surprisingly, dependent upon reality as a basis of imaginary construction” (Chapman 1931). Today we might simply consider Austen a“realist,” but this conception of the novel would not gain currency until the 1850s. From Austen’s own point of view, it is more likely that she was seeking that fine balance between imagination and “the accurate observation of the living world,” which Samuel Johnson had praised in his influential essay on the novel in The Rambler, March 1750. Nonetheless, Chapman’s intuitions seem right, in that the more one examines this aspect of Austen’s writing, the more exceptional her dependency appears. There is something very insistent and seemingly concrete about her geolocations, even if, at the same time, they can appear very abstract.

If we compare Austen’s work with that of Henry Fielding, we can see how strikingly innovative it is. We know roughly where Fielding’s country places are set, but we could never locate them on a map because he gives mileages infrequently, and in round figures, saying a place is “about 200 miles from London,” “within a hundred miles of the place,” “a full six miles” or “two miles off.” Such distances indicate remoteness or proximity but are too imprecise to enable geolocation. They are also relatively rare, appearing once in ten thousand words in Tom Jones. In Austen’s works, mileages are twice as frequent, and nearly always seem precise (as, for example, “sixteen miles” in Emma, “twenty-four miles” in Pride and Prejudice). Such designators are rare in Austen’s juvenilia but appear with increasing frequency in her published works: 12 times in Sense and Sensibility; 26 times in Pride and Prejudice; 34 times in Emma, her most static novel; and 47 times in the three-volume posthumous publication of 1817 (i.e. 19 times in Persuasion and 28 times in Northanger Abbey). Mansfield Park is the odd one out, having only 20 uses of “miles.” Throughout, many of the key places have more than one distance marker provided, which creates the impression that the location could be established by triangulation, augmenting the sense that a “feigned” place can be found, even if the name is fictitious. MacKinnon devoted much of his 1926 article to defenestrating the many proposals which earlier critics had made for the real-world locations of Austen’s feigned places, and to do this he used the kind of critical method one would expect from such a distinguished barrister and High Court judge, forensically proving that one place was too far from another and therefore did not fit with the case, and so on. His method, however, has a way of fueling the fire he is trying to put out, recognizing that her imagined places seemed to have very real locations, even when there is little textual information to support this effect.

Five years after the publication of his essay, MacKinnon almost fell into the same trap he had critiqued: he wrote a jocular letter to R.W. Chapman saying that during an afternoon walk he had identified the location of Mansfield Park as Cottesbrooke, Northamptonshire, and asking Chapman if he knew of any connections between Austen and this house. Chapman replied he did not, but a little later he turned up the fact that Cottesbrooke had belonged to Sir James Langham, whose wife had been a friend of the wife of James Tilson, Henry Austen’s banking partner (Chapman 1931). When Chapman published his speculative suggestions in the TLS, Mackinnon wrote publicly disagreeing with Chapman, saying that Cottesbrooke is 76 miles from London, whereas Mansfield Park is 70 miles, which is “against the identification” (Mackinnon 1931). Precision must be precise, after all. Today, however, notwithstanding his critical demurral, Cottesbrooke Hall is often visited by Austen readers on the slender basis of Mackinnon’s remark. I offer my own candidate for Mansfield in Chapter 11 of this book.

The Cultural Context of Austen’s Geographies

Personal Travel

An obvious explanation for why Austen uses precise mileages to create the impression of precise locations is that during her lifetime there was a vertiginous increase in personal travel, and therefore in the regular use of such aids to geolocation as maps, guides and road books. The figures are worth recording: modern historians have estimated that personal passenger miles increased from 183,000 in 1773 to 1 million in 1796, and to about 2 million in 1816 (Albert 1972, 189; Chartres and Turnbull 1983, 72). Given that the population increased in the same period from 7 to 10 million, the increase in passenger-miles-per-person-per-year was about eight times, from one mile for every 38 people to one mile for every 5 people. However, since most of this travel would have been undertaken by a tiny percentage of the population, so the expansion in personal travel for those who had the leisure to read novels would have been perhaps thirty times. These readers were becoming very much more geographically aware.

The increase in personal geographical mobility was made possible by private companies building turnpikes, particularly from the 1750s onwards. Turnpikes provided good all-weather surfaces in return for tolls paid, and thus enabled coaches to travel at the gallop, changing horses every 10–15 miles, maintaining average speeds of 7–8 mph. As the turnpike network matured, so it enabled the development of national post-coach service. In August 1784, when Austen was nine years old, John Palmer, the architect of Bath and friend of William Pitt, the prime minister, staged a trial journey from Bath to London, a distance of 110 miles accomplished in 16 hours. The outcome was considered so impressive that by one year later twelve cities were being served, including Edinburgh, and by 1810, when Austen was working on the final draft of Sense and Sensibility, all major towns and cities in the kingdom could be reached by fast and regular coach services and mail was being delivered to major towns and cities as frequently as three times a day.

Road Books and Maps

Contemporary readers of Sense and Sensibility would probably have assumed that Colonel Brandon took a post-coach when he abruptly canceled the proposed outing to Whitwell and left Barton, 4 miles north of Exeter, for London. A post-coach would have enabled him to cover the 170 miles in 2 days. Readers may also have assumed that he carried in his pocket a “road book” which would give him a guide to mileages between towns, as well as the names of gentleman’s houses he might see along the road, the times of coaches and days of markets in the towns served. Amongst the most successful of these books was Daniel Paterson’s A New and Accurate Description of all the Direct and Principal Cross Roads in England and Wales, and Part of the Roads of Scotland, first issued in 1771 and reissued eight times by 1804. If Brandon had not carried a copy of Paterson, then he would have chosen Cary’s Traveller’s Companion, first published in 1787 by John Cary, one of the best cartographers of the age, and revised in 1792, 1810, 1814 and 1817. In 1781, Cary had been commissioned by the Postmaster General to map the new post routes, and the result was Cary’s New & Correct English Atlas (1787–88), a byword for accuracy for the next fifty years and the primary source of Paterson’s information. Such atlases made the whole island of Great Britain visibly comprehensible as a lattice of mileages, important towns, major routes from London, cross routes between major towns and cities, and even salient tourist attractions. It is often said that the building of the railway networks between 1835 and 1840 brought standard national time to the island, and equally often forgotten that already in Austen’s lifetime the island had become rationalized in terms of calculable space and time (Blanning 2007, 34–39).

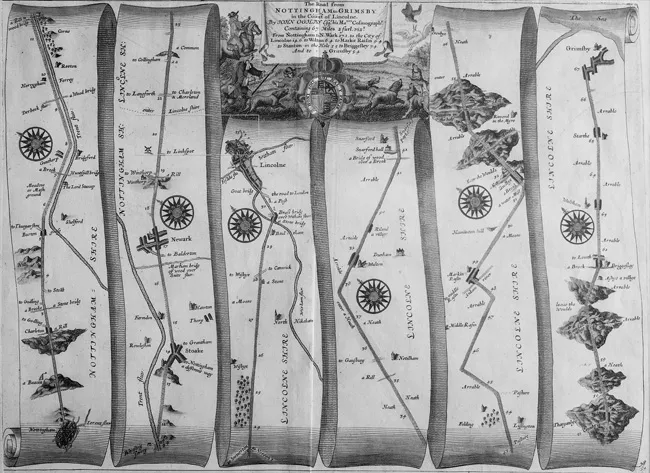

Road books and the atlases which accompanied them were built upon nearly two centuries of county mapping which began with the first complete set of maps made by John Speed for his richly ornamented The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, published in 1610/1611. These were followed by the more workaday maps in Thomas Jenner’s A Direction for the English Traviller, by which He shal be Inabled to Coast about All England and Wales (1635) which appeared in at least 15 editions before 1677. Less ornamental and crudely printed, this work was among the first to provide tables of mileages between major towns and cities. In 1675, both efforts were pushed to the margins by the extraordinary achievement of John Ogilby’s Britannia, an enormously expensive folio edition comprising 100 strip maps which collectively represented the 2519 miles of major roads and cross roads in England and Wales (Figure 1.1).

It was Ogilby’s careful measuring of distances which standardized the length of the English statute mile at 1760 yards, and which furnished nearly all the information on distances which Austen’s contemporariesfound in their road books. Ogilby’s maps were reprinted in a pocket format with additional commentary by J. Owen and E. Barr in various editions of Britannia Improv’d from 1720 to 1767, nourishing the work of later cartographers. Other reeditions of William Camden’s Britannia, such as Bowles’s Britannia Depicta, or Ogilby Improved (1764), reprinted Ogilby’s maps in small and more affordable works, and, in Austen’s own lifetime Richard Gough’s edition of Britannia in 1789 extended came out in three (later four) sumptuous folio volumes, providing learned readers with good county maps and all manner of information, historical and contemporary. Gough’s edition was revised and reissued by John Stockdale in 1806, an edition which might well have been consulted in Edward Knight’s library at Godnestone by Jane Austen (Doody 2015, 225). Such publications for the wealthy had cheaper counterparts in works which signal the emergence of geography as part of the educational curriculum for the well-brought-up. Johann Huebner’s A New and Easy Introduction to the Study of Geography was first published by Thomas Cox and James Hodges in 1742, and was reprinted five times by 1777. Its place was then taken by Richard Turner’s A New and Easy Introduction to Universal Geography which went through 13 editions between 1780 and 1808. It is clear that such characters as Camilla in the juvenile story “Catharine, or the Bower” was unaware of these books, or had digested them very badly, since she believes you can go from Derbyshire to Matlock, not realizing Matlock is in Derbyshire (C, 250), her geographical carelessness mirroring her moral disorientation, as Ana-Karina Schneider discusses later in this volume.

Ordnance Survey Maps

Whilst such publications would have furnished Austen from her childhood with a clear and accurate understanding of English geography and her place within it, her maturity also coincided with the publication of the First Series of Ordnance Survey maps. The Board of Ordnance was a civilian body charged since Tudor times with the maintenance of military facilities for defense of the realm and its overseas possessions. It was therefore engaged in the manufacture of weapons and explosives, the training of personnel (the Corps of Artillery), and the construction of fortresses (the Corps of Engineers). The 1745 campaign to “pacify” the Scottish Highlands after the Battle of Culloden exposed the need for accurate topographical maps to facilitate wars of movement, so the Board commissioned Lieutenant William Roy to map the entire mainland of Scotland at one inch to 1000 yards. Between 1747 and 1752, this was accomplished with such success that in the following years the Board mapped many parts of the British Empire where the military was engaged, notably Quebec (1760–61), the east coast of North America (1764–75), Florida (1765–71), Bengal (1765–77) and Ireland (1778–90). In 1756, Roy also reconnoitered sites at risk of French invasion along the south coast of England, and in 1766 he pressed for the creation of a “General Military Map of England,” emphasizing that whilst extant county maps were accurate enough for navigational purposes, the paucity of topographical information made them inadequate for military operations (Hewitt 49). Roy’s proposal was not taken up, but work went ahead to improve mapping technology, notably learning from the work in France where the “Depôt de Guerre,” a body not unlike the Board of Ordnance, commissioned the Cassinis to produce the first entire, uniform, detailed and accurate map of a modern nation state using their new method of triangulation. Jerry Brotton has pointed out that the Cassini maps gave many of the French their first understanding of how their own small locality belonged within the national whole, and added immeasurably to the visual and ideological conceptualization of the nation state (Brotton 2012, 294–336). Every square centimeter now took its place in a divinely ordained, scientific and rational scheme of things. The mentality was soon emulated by the British: in June 1784 Cassini guided William Roy, as he laid out the base line for the triangulation of Britain on Hounslow Heath. Progress with this project was slow until 1793. War with France, and the fear of invasion, then gave it urgency. Roy’s 1766 proposal was dusted off, a “Military Map of Kent, Sussex, Surrey and part of Hampshire” (invasion targets) was soon underway, pioneering what became the Ordnance Survey. Significantly for readers of Austen, the very detailed maps which then appeared focused on counties in which she had particular interest: Kent where her father was born and Edward had his major estates, was the first of the maps to be published, on January 1, 1801. This was followed by Cornwall (1803), Essex (1805), Devon (1809), the Isle of Wight and Hampshire (1810), and other parts of Hampshire (1811) (Seymour 2–7, 62–67). These maps, and the cultural importance and strategic importance given to them, surely influenced Austen’s and her readers’ geographical conceptions.

Leisure and Luxury: Games, Letters, Tourism

This great transformation of geographical understanding was not only experienced through maps, road books and actual travel, it was also experienced in the wider culture through personal letters and social gossip, and through diverse references in newspapers, novels, essays, memoirs, plays and travel writing. In such diverse publications, we can chart the subtle but profound shifts in consciousness that are occurring, for example appreciating how the new accessibility of what was once remote changes the relationship between the local and the national, the provincial and the metropolitan, as Pat Rogers does in his essay in this volume, reflecting on how representations of the West Country change between Fielding and Austen. Whilst literary writing charts and shifts such changes, the less learned—perhaps the ignorant Miss Bertrams in Mansfield Park—might develop their geographical understanding through such sociable amusements as geographically themed playing card games, which had been in...