![]()

Drama

For many people the term ‘drama’ is synonymous with ‘theatre’. Misconceptions have arisen from this which create expectations and unnecessary anxiety about its use in therapy. There is a difference in that drama is a personal experience in a group and theatre is communicating the experience to others. Baz Kershaw (personal communication) puts it succinctly: ‘Drama is primarily concerned with the personal growth of the individual as part of a group; theatre raises the results of that growth to public significance through metaphorical presentation’. Of particular interest to those involved in the psychology of personal adjustment is the fact that drama came into being from the time that man first began to explore himself in relation to his environment, and goes far beyond the confines of theatre. This exploration stems from man’s desire to create and drama has creativity as part of its being. It engages the imagination to look at and explore attitudes rather than characters. Drama is about extending boundaries of time and place as far as they can go and our emotional responses to them. It poses the question – ‘What if?’ – allowing us to look at the possibilities of where a situation could lead if allowed to go to its limits, and alternative ways of getting there. The process is one of exploration through interaction and it happens in the present although we may be concerned with events of the past or future. It seeks to answer the question – ‘What if?’ – through action and interaction, sharing that experience both with other people and our environment. In the process, drama can make use of other art forms: music, painting, dance, sculpture, etc.

Theatre

The conventional idea of theatre is that of a stage and auditorium with tiered seats, an idea which most of us have experienced. In recent years there has been a loosening of the concept to admit that theatre can take place without a stage and that props, lighting and costume are not necessary. As Peter Brook (1968) says – ‘I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space while someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.’

Theatre has its roots in religion. The early rituals in which people participated taught them about the gods. The dramatic experience of these rituals was a way of coming to terms with the environment and its problems. The myths with which we are familiar were developed and became part of the whole experience. It was the Greeks who created theatre as we know it. They built theatres with a stage and auditorium and encouraged writers to produce scripts for actors to present to the audience. In medieval times Mystery Plays were produced by the church to teach bible stories to the congregation, most of whom could not read. The actors were members of the congregation and the plays were performed in church. Later, Morality Plays came into being in order to teach the ethics which stemmed from bible stories. As these became more earthly in content, they also became more bawdy, until finally the church could not tolerate them and the players took to the streets and acted there. It was the rise of the Guilds who supplied actors for traditional parts in plays that finally produced acting as a profession. One member from each Guild was sent to take part in the local pageant. As it became the custom for one person to be selected more than others, he gradually became the actor for his Guild until, by Shakespeare’s time, acting had become recognised as a profession in its own right. Actors were usually itinerant, travelling with a cart which served both as transport and stage. Plays were still a means of teaching, not only about church doctrines, but also about life in general and were a way of presenting topical issues to the people. They were ‘a mirror held up to nature’ (Hamlet).

Today we think of actors as highly skilled professionals or amateurs with varying skills developed as a hobby. In either case the standard to which they perform dictates the enjoyment and insight which the audience gains from it. The higher the standard of production, the more (usually!) the enjoyment. So whether the performance is professional or amateur, it is a play, mime or sequence of events presented to the audience who enjoy it or not depending on standards of writing and acting. The higher the standard the more likely it is that theatre will teach us something about ourselves and give us an increased sensitivity to the issues portrayed. The audience, however, are not passive recipients but react among themselves by laughter, applause, silence, coughing, etc., and so communicate their feelings to the actors. This actor/audience relationship becomes a shared experience in which a sympathetic understanding can be created. Unlike drama, theatre must have an end-product and the final presentation is the result of a period of rehearsal. However, each performance is unique in that it happens at one particular time, is shared by the people present (both actors and audience) and because their varied experience and personalities are peculiar to that moment.

Therapy

A visit to the theatre, a game of golf, painting, playing the piano and many other activities, we frequently say ‘lifts us out of ourselves’, makes us ‘feel better’, ‘forget our problems’, ‘feel more relaxed’ or ‘feel more refreshed’. All these terms imply change in some way. We are probably all dissatisfied with some part of our lives and our ability to effect a change to a more desirable state depends on our intelligence, personality and experience in life. We are motivated towards a set of goals which can be variously described, but one useful way of looking at this is that of Maslow (1943). He says that ‘There are at least five sets of goals, which we may call basic needs. These are briefly physiological, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualisation. In addition, we are motivated by the desire to achieve or maintain the various conditions upon which these basic satisfactions rest and by certain more intellectual desires.’ He goes on to say that we have a hierarchy of our basic needs which may change from time to time, but one always emerges as more dominant than the others. As soon as that need is gratified it no longer becomes an active motivator, so we are always striving for something else (see also Chapter 3). If we are unhappy, creative activities can lift us out of ourselves, thus effecting a change. Treatment (or therapy) in a strict medical sense of healing is also bringing about change – changing symptoms in the direction of health. Creativity can produce emotional change in healthy people. Changing people with emotional disorders to a primarily creative experience can, therefore, be regarded as treatment. The treatment of emotional disorders involves changing emotions and attitudes in the direction of health. Creative activity, i.e. drama, produces change in a similar direction.

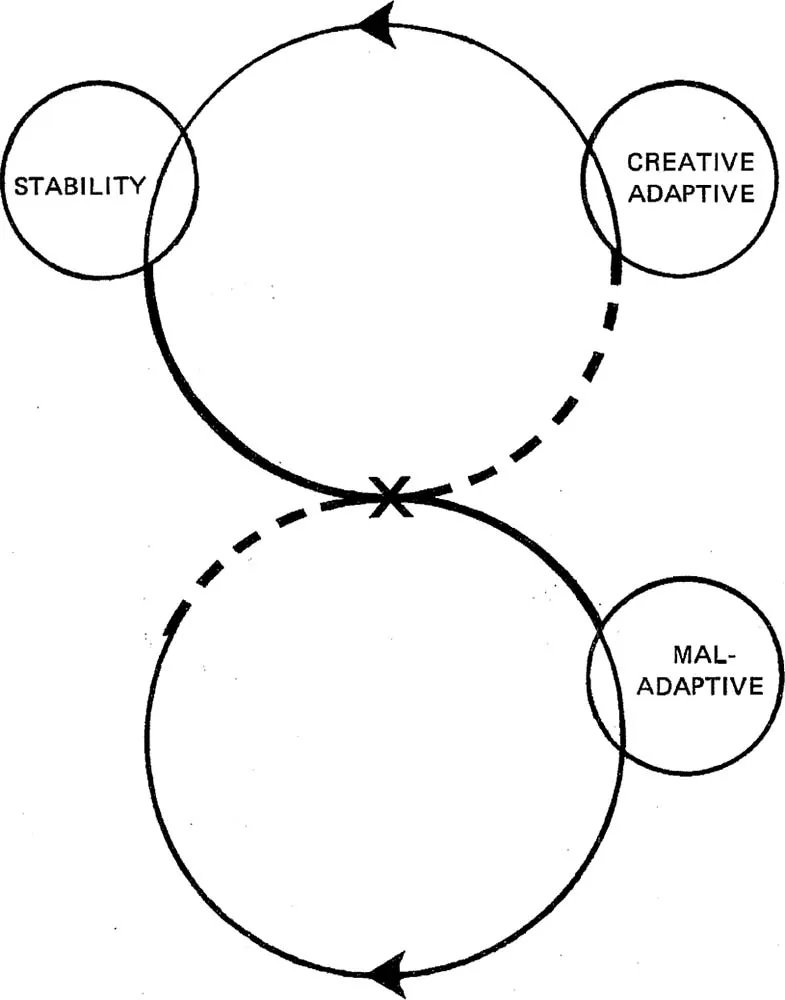

It is easier to accept change at some times than at others. While some people may become paralysed into rigid inactivity, Kaplan (1961, 1964) postulates that the crisis of illness heightens some people’s willingness to consider change. If we consider a state of equilibrium (i.e. health) to be the most desirable state, then we can see how a crisis such as illness or anxiety is a stimulus to change and so upsets the balance. In order to restore this balance, we resort to either adaptive (constructive/ creative) behaviour or maladaptive (neurotic) behaviour. The latter, although producing short-term gain is, in the end, self-defeating. For if we choose the latter, we find ourselves in a vicious, maladaptive circle which, if treatment is to be effective, has to be broken at the point of contact with the adaptive circle and emerge constructively redirected to get on the path to equilibrium again (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Maladaptive Behaviour Will Not Restore Stability

Therapy, in my definition, involves creating an environment in which healing can take place, so anything that facilitates a move from the maladaptive behaviour towards the adaptive and personal equilibrium can be described as therapeutic. Although we all hope to reach the goal of equilibrium, therapy does not discount temporary or incomplete change as being valuable. Therefore, if someone ‘feels better’ following some activity, the temporary change is no less valid than a permanent one. A number.of such changes could be additive and become more enduring. However, the creation of an environment conducive to change does not necessarily mean that the recipient will take advantage of it. We create the environment and use certain therapeutic tools, but it is ultimately a matter of whether the client will allow the change to take place. It is as well to remember that the client does not owe the therapist a change, so the therapist must not be continually expecting it. If change takes place it is because the client has allowed it to happen and not because the therapist has done something for him. Sometimes the ‘therapy’ has to be geared towards motivation. Then the first goal is that of changing from a complacent acceptance of his present state to a desire for. change. This is a decision only the client can make and cannot be forced upon him.

The Therapist

People come into training as therapists for varying reasons. Such reasons are personal to us and our desires to give/receive, be accepted/rejected, be of value, or in authority, or to compensate for something we feel lacking, or to relate to other people, are all involved. Whatever our motivation, both conscious or unconscious, we come into training to acquire skills in order to help others change. Training will vary according to our professional discipline and the school at which we learn it. But if we are facilitating change in others, we must be aware of aspects of our own personalities which need to change. If we do not deal with our own major conflicts and prejudices they are likely to influence our attitude towards our client’s conflicts. This personal development does not cease on qualification as a therapist. As we continue to change we discover new areas of ourselves of which we may have been unaware. We may see ourselves reflected in our clients and need to come to terms with our own neurotic traits and behaviour. If we are not open to such change ourselves, we may be depriving our clients of the opportunity of maximum growth in a professional relationship. As the therapist broadens his own experience and develops as a person as well as in terms of professional skills, he will also grow in confidence and be able to modify his own ideas as the client unfolds his personal conflicts and problems. We need to be flexible both in our skills and our attitude towards the client. We need to be sensitive to a loose concept of what a patient’s illness/behaviour is about. As we know him better we maybe need to change our ideas about him. Therefore we need to be free in ourselves and able to modify our views.

Dramatherapy

The use of the arts in therapy is not new. When David played and sang to Saul it was to soothe the rages of his epileptic temperament. The creative experience was a tool which helped bring about a change of mood.

I would define dramatherapy as the use of drama as a therapeutic tool. It is not, as in theatre, an acquired skill which people can or cannot do, but a medium in which each person can participate at his own level. It is an extension of the natural play that we all know as children that gives people the means to become more creative and spontaneous beings. For the client there is no standard of performance in the theatrical sense. The therapy is in the doing. It is concerned with all the arts and overlaps with many other activities. By the use of games and improvisation (spontaneous scene) we help the promotion of personal growth. The main ways in which we do this can be listed as follows.

Trust: We need to promote trust within all our group members. Usually patients will trust staff members easily, but we need to work harder to develop trust with their fellow clients. A simple exercise like allowing another person to lead you around the room with your eyes closed invites trust from the one and responsibility for another person from the other.

Group Cohesion: Simple games can become a shared experience. Touching games, working and talking in close physical proximity, and games requiring group decisions help to form a sense of group identity.

Imagination: Can be stimulated by guessing games and mime. It is important that adults retain and use their imagination. We often see this as something belonging to childhood, but in fact we need to use our imaginations in problem-solving. If we cannot imagine where a situation can lead, we may find ourselves in trouble. Likewise, if we cannot imagine the limits of an action, we may also find ourselves in a situation with which we cannot cope. Derek Bowskill (1973) writes ‘Imagination enables us to cut through the probable, achieve the possible and glimpse the unattainable.’

Memory: Can be stimulated and exercised by music and games.

Projection Techniques: Can be fun if presented as games.

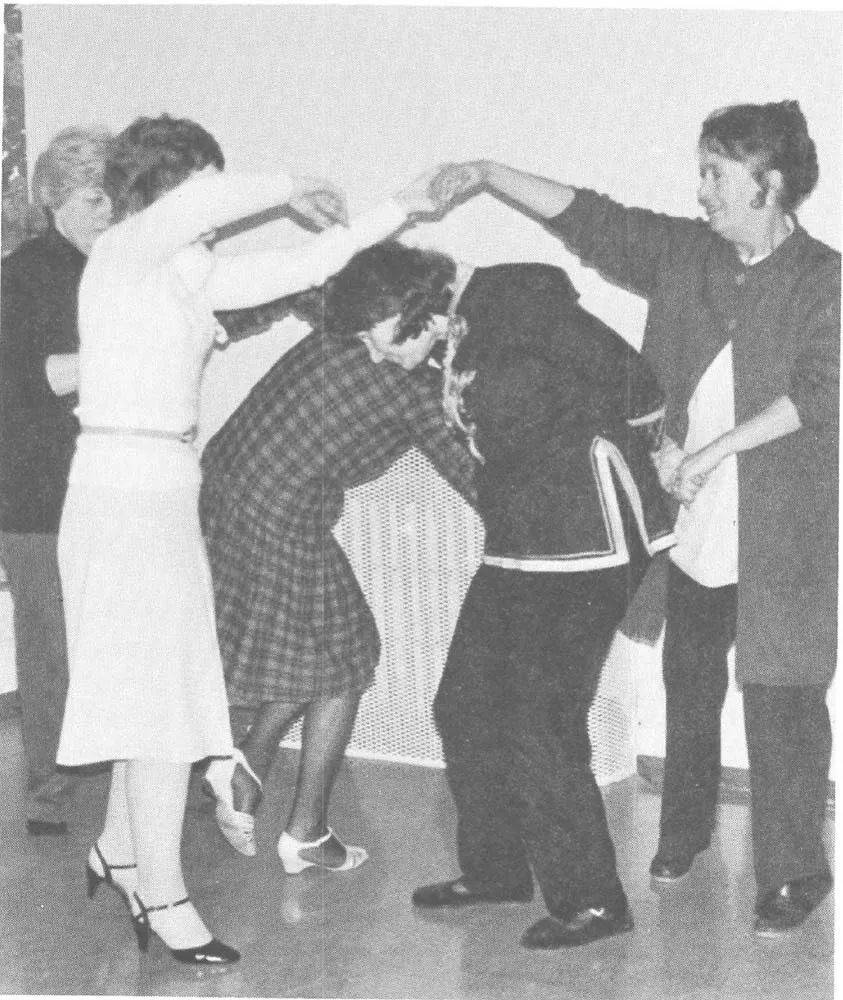

Sensory Perception and Physical Awareness: Games can be used to develop all the senses. Physical contact allows people to learn to become aware of the feel and sounds of their own and other people’s bodies without feeling anxious (Figures 1.2 and 1.3). The image people have of their own bodies is sometimes relevant to their behaviour.

Movement: This is important to us all. If we do not use our muscles they cease to function properly. Movement can be enjoyed for its own sake or as a means to achieving an end. The way we move is also an important non-verbal communication in body language. Long-stay patients with few activities and depressed people who are concerned only with their problems have little motivation for movement. In drama we can give some kind of stimulation and motivation for movement.

Figure 1.2: Physical Proximity – Group Tangle

Figure 1.3: Physical Proximity - Warmth and Pressure

Relaxation: This goes hand-in-hand with movement. The greater the tension we put on our muscles, the greater the relaxation when we let it go. Relaxed bodies lead to relaxed minds, and tension, both physical and mental, is common with our clients. They need to learn not only how to relax to sleep at night but also how to move in a relaxed way and so ease tense muscles.

Concentration: Can be encouraged by simple games and activities.

Communication: Both verbal and non-verbal communication can be explored and if necessary learned in drama sessions. Sometimes people are inhibited in a social situation becau...