eBook - ePub

Advances in Chromatography

Volume 56

Nelu Grinberg, Peter W. Carr, Nelu Grinberg, Peter W. Carr

This is a test

Share book

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Advances in Chromatography

Volume 56

Nelu Grinberg, Peter W. Carr, Nelu Grinberg, Peter W. Carr

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

For more than five decades, scientists and researchers have relied on the Advances in Chromatography series for the most up-todate information on a wide range of developments in chromatographic methods and applications. The clear presentation of topics and vivid illustrations for which this series has become known makes the material accessible and engaging to analytical, biochemical, organic, polymer, and pharmaceutical chemists at all levels of technical skill.

Key Features:

- Includes a chapter dedicated to Izaak Maurits Kolthoff, offering a unique look at his non-professional life as well as his impact and legacy in Analytical Chemistry.

- Discusses recent advances in two-dimensional liquid chromatography for the characterization of monoclonal antibodies and other therapeutic proteins.

- Reviews solvation processes, methodologies of their measurement, and parameters influenced solvation

- Explores recent advances in TLC analysis of natural colorings, determination of synthetic dyes, and determination of EU-permitted natural colors, in foods.

- Offers comprehensive and critical insights on the key aspects of CE-MS analysis of intact proteins

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Advances in Chromatography an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Advances in Chromatography by Nelu Grinberg, Peter W. Carr, Nelu Grinberg, Peter W. Carr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | Kolthoff of Minnesota |

CONTENTS

Foreword

1.1 Introduction

1.2 The Chemist

1.3 The Professor

1.4 War

1.5 Subversive

1.6 The Father of Modern Analytical Chemistry

1.7 Epilog

Acknowledgments

End Notes

FOREWORD

Izaak Maurits Kolthoff was doubtlessly the preeminent analytical chemist of the twentieth century—certainly in the United States and perhaps in the world. Educated in the Netherlands, Kolthoff adopted as his own the scientific motto of his esteemed mentor: “Theory guides; experiment decides.” Kolthoff’s mentor Professor Nicholas Schoorl had obtained his degree studying with the great Jocobus van’t Hoft who was the first Nobel Laureate in Chemistry (1901). The influence of his scientific background in physical chemistry is clear both in Kolthoff’s research and his teaching. His life’s work became the transformation of a highly descriptive empirical branch of chemistry, namely chemical analysis, into the science of analytical chemistry, building on the physicochemical principles and concepts introduced by the founders of physical chemistry (such as Arrhenius and Ostwald). Although not a practitioner of chromatography, Kolthoff was the chief architect of much of the foundational chemical science upon which analytical chemistry and separation science are built.

Professor Kolthoff published his first paper in 1915. It concerned acid–base titrations using the recently developed theories of weak and strong electrolytes of Arrhenius and Sorenson’s concept of pH. Because of his worldwide reputation ensued over the next 18 years, he joined the University of Minnesota in 1928, where he remained a faculty member until his so-called “retirement” in 1962. He published more than 800 papers during the “active” years of his career, and an additional 150 papers appeared before his health failed. He maintained a National Science Foundation grant until only two years before his passing.

Professor Kolthoff’s research, covering a dozen areas of chemistry, focused primarily on constructing a firm scientific foundation for analytical chemistry. He and his students studied basic aspects of acidimetry, alkalimetry, establishing the pH scale using acid–base indicators, gravimetric analysis, iodometry, the theory of colloids and adsorption (especially important to chromatography) and crystal growth, thereby establishing the scientific basis for gravimetry. His work with acids and bases, in which he was the first to fully apply the Arrhenius theory (1884), developed the rational choice of end point indicators and transformed titrimetry from a practical art to a quantitative science based on sound principles. Kolthoff’s work in acid–base chemistry—both in aqueous and non-aqueous media—is of seminal importance throughout the science of chemical separations. He developed the theory of potentiometric analysis and potentiometric titrations, as well as conductometric titrations. When Jaroslav Heyrovsky, at the Charles University (Prague, Czechoslovakia), discovered polarography (1925), for which he received the Nobel Prize (1959), Kolthoff immediately recognized both its scientific significance and practical importance. Indeed, it eventually led to important methods of environmental trace metal analysis and biological sensors in use today; it is also the basis of amperometric detectors, which are vital to chromatographic detection of neurotransmitters in analytical neurochemistry. Kolthoff’s fundamental studies of diffusion and mass transfer as they pertain to electrochemistry and electroanalytical chemistry account, in part, for why so many of his students and their progeny became interested in chromatographic science. He and his students, especially James J. Lingane (PhD, 1938, Harvard University) and Herbert A. Laitinen (PhD, 1940, University of Illinois and Florida), contributed significantly to the understanding and use of electroanalytical methods such as polarography and ion-selective electrodes.

Throughout his career Kolthoff emphasized the role of chemico-physico principles in chemical analysis. Thus he was one of the earliest to understand the fundamental significance of the chemistry of crown ethers and cryptands and recognized the work of Jean Marie Lehn, who ultimately received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1987) for his work with cryptands. Lehn was the inaugural Kolthoff Lecturer at the University of Minnesota (1979).

In addition to his phenomenal production of research publications, Kolthoff wrote and edited many books, including the multivolume monograph Volumetric Analysis (with Vernon Stenger, PhD, 1933); Polarography with J. J. Lingane; and Potentiometric Titrations with H. A. Laitinen. Kolthoff was also editor-in-chief of the Treatise on Analytical Chemistry (19 volumes in 2 editions) and the inaugural editor of the series of monographs entitled “Chemical Analysis,” which continues till this day. Many of the Chemical Analysis monographs are devoted solely to separation science.

Arguably his single most influential book was “Quantitative Inorganic Analysis,” co-authored with his first doctoral student, Ernest B. Sandell (PhD, 1932). Widely recognized as the progenitor of all modern textbooks on analytical chemistry, it appeared in four editions (the last co-authored with colleagues Sandell, Meehan and Bruckenstein) and six languages (including Russian and Japanese).

His myriad contributions were recognized throughout the world. Being a member of the National Academy of Sciences, he received the American Chemical Society’s Nichols Medal and the Fisher Award for Analytical Chemistry. He was the first recipient of the Kolthoff Award of the American Pharmaceutical Association.

His work with the most direct public impact came during the Second World War. Arriving in the United States from the Netherlands, where his family was virtually wiped out during the Nazi occupation, Kolthoff quickly assembled an extensive research group that made major contributions to the synthetic rubber program. He and his coworkers held several key patents related to synthetic rubber.

Chapter 1 in this volume is virtually unique in that it focuses more on Kolthoff’s non-professional life, about which very little has been written compared to the extensive papers, interviews, and summaries emphasizing his profound scientific contributions. Perhaps the most detailed of these is the National Academy of Science memorial on Kolthoff written by his student Professor Johannes Coetzee (PhD, 1957), late of the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

As Paul Nelson details below, following the war, Kolthoff was deeply engaged in many humanitarian efforts. He was an early supporter of the United Nations, and as a promoter of world peace, he corresponded extensively with Albert Einstein, Pierre Joliot-Curie, Senator Hubert Humphrey, and Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt. He was also an early critic of Sen. Joseph McCarthy.

Many of his graduate students, including Sandell, Lingane, and Laitinen, went on to very successful careers in industry and academic life at institutions such as Harvard University, MIT, Northwestern University, the University of Chicago, the University of Michigan, the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania State University, the University of Illinois, the University of California (Berkeley), and other major US research centers. By 1982 more than 1,100 PhDs could trace their scientific roots to him. The number of undergraduate students who learned from him, his students, or his books is incalculable. He stated to this author that the recognition that gave him the greatest pleasure was the American Chemical Society Division of Analytical Chemistry’s inaugural Award for Excellence in Education, in 1983. In the words of James Lingane, “[A]nalytical chemistry has never been served by a more original mind, nor a more prolific pen, than Kolthoff’s.”

It was my honor and privilege to be a third-generation Kolthoff PhD, and subsequently to become his colleague while he was emeritus professor at Minnesota, where friends and colleagues knew him simply as “Piet,” a shortening of his childhood nickname Pietje (roughly “little fellow”). We met for lunch and a chat almost weekly and sometimes on weekends. We discussed his many interests and reminiscences. Through him I met many of the international leaders in analytical chemistry, including chromatographers such as Phyllis Brown, Les Ettre, and Al Zlatkis, who, whenever in the Midwest, made a pilgrimage to Minnesota to visit with Piet Kolthoff.

Peter W. Carr

Professor of Chemistry

University of Minnesota

July 9, 2018

1.1 INTRODUCTION

On August 5, 1927, Dr. Samuel Lind, dean of the Institute of Technology at the University of Minnesota, sent this cablegram:

University of Minnesota Minneapolis desires full professor analytical chemistry. Kruyt recommends you. Would you accept visiting professorship for coming year October to June for $4500 with permanent position in view? These few lines yielded riches for the university, in honors, teaching, scientific achievement, and, yes, money, beyond anyone’s imagining.

The recipient was Izaak Maurits Kolthoff, a 33-year-old lecturer at the University of Utrecht, The Netherlands. Kolthoff did not know Lind, had never been to Minnesota, and might have been surprised to learn that a somewhere university bore that peculiar name. Three days later, Kolthoff cabled back his acceptance. Thus began a relationship that lasted 66 years.1

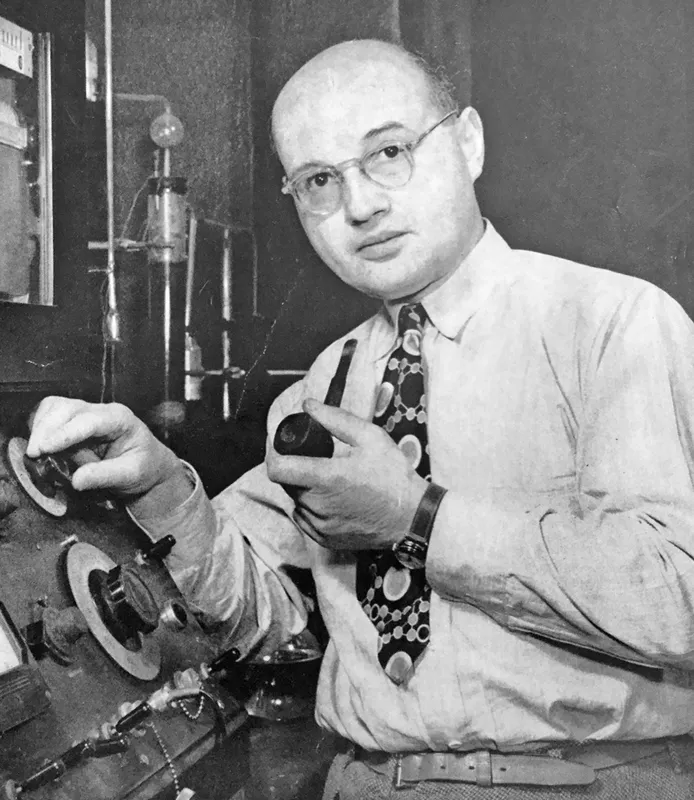

Kolthoff in laboratory, 1940s. University of Minnesota Archives, University of Minnesota—Twin Cities.

1.2 THE CHEMIST

“Don’t worry, mama, I will restore your chicken soup to its optimal pH.” Such is the gist of a story that Piet (his nickname from childhood, pronounced Pete) Kolthoff liked to tell and that he told often. He was 15 years old and had converted part of the family kitchen into a makeshift chemistry lab.

One day I got in the kitchen and found my mother desolate. By mistake Mother had put in the chicken soup … several large spoonfuls of sodium carbonate [baking soda] instead of sodium chloride [table salt.] She was just ready to throw everything into the sink when I told her that it was child’s play to transform the carbonate into sodium chloride. Thus, I made my first titration, adding hydrochloric acid until—at a pH of 7—litmus paper turned violet. This, in my experience, is still the optimum pH of chicken soup.2

Whether this story is entirely true may be doubted,3 but no matter—it tells a truth about young Piet Kolthoff. He loved chemistry and, very young, dove in deep.

Kolthoff was fortunate then to be both bookish and Dutch. The elite public high school in Almelo, his home town, demanded a commitment to studies that even today’s over-stressed American high school achievers would find exhausting: plane and solid geometry, algebra, economics, world and national geography and history, 3 years of organic and inorganic chemistry, 4 years of English, 5 years of German, and 8 years of French. It suited him.

Completing the coursework marked a good start, but this was only a start. Then came two-and-a-half weeks of written tests, followed by oral exams. “For the oral exams we submitted a lists of 20 books … we had been required to read in English, German, and French (not to speak of Dutch.) The two examiners could choose any one or more of these books and in addition to giving a summary of the contents by the candidate they would interrupt with questions.” The language exam consisted of questions about the same books but in the language of the book. Fifty-five students started in Kolthoff’s class; he and 10 others made it through.

This achievement still did not qualify him for a regular Dutch university, because he lacked knowledge of the Greek and Latin languages. So, in 1911, he enrolled in the pharmacy program at the University of Utrecht. He chose it so that he could get in, because the pharmacy program did not differ much from the chemistry program, and to study under Nicolaas Schoorl, professor of pharmaceutical and analytical chemistry.

As a second-year student at Utrecht, Kolthoff had come upon a book by Wilhelm Ostwald, The Scientific Foundations of Analytical Chemistry—and what youth could resist this title? There, he read that analytical chemistry, “the art of recognising different substances and determining their constituents...