I Understanding the problem

Examples from medicine

By removing the handle from a water pump, the Victorian doctor John Snow greatly reduced the incidence of cholera during an outbreak in a small area of central London. By intervening early and thus preventing people drinking bad water he succeeded in inhibiting the transmission of a disease. Some aspects of the story may be apocryphal, but the central image of him rolling up his sleeves before the Broad Street pump is very striking and it has encouraged many scientists, policy makers, managers and practitioners to seek similarly forthright solutions to other health and social problems. Far better to take decisive preventative action than to wait for a disease to take hold.

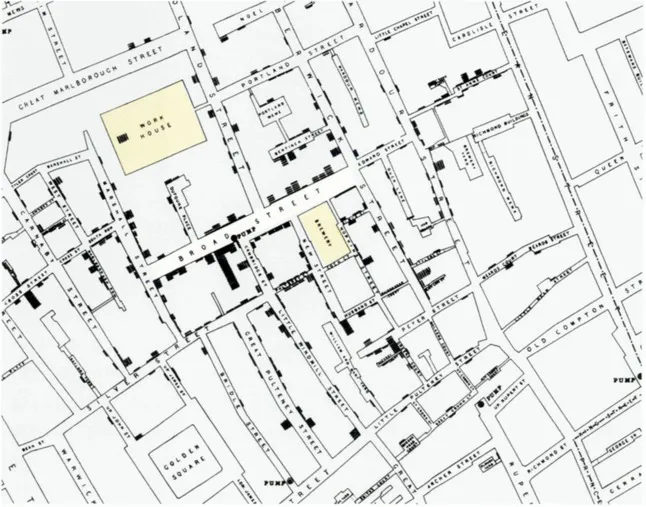

John Snow studied the incidence of cholera by location. His concern was less for the experience of the individual than for the connection between groups of people who died after experiencing similar symptoms: in this case, those caused by the cholera bacteria. This map, which marks each death in its approximate location with a coffin shape and relates the deaths to the position of street water pumps, represented an important breakthrough in his understanding.

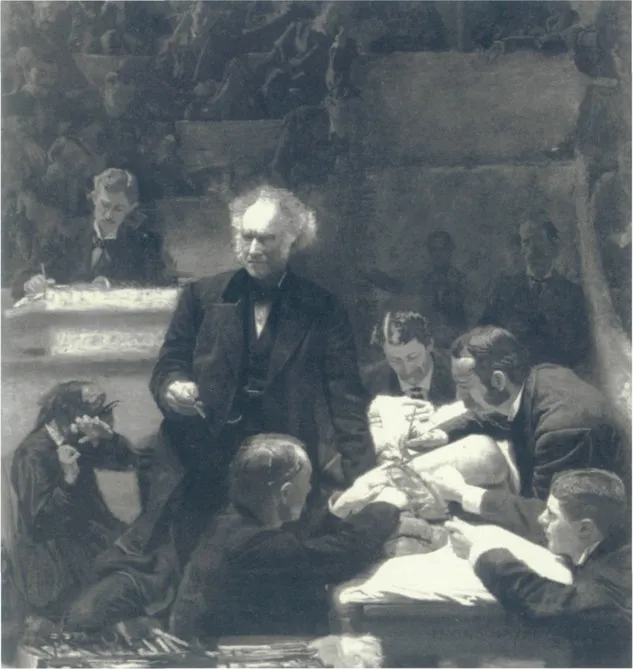

From his geographical detective work, Snow began to understand certain chains of effects. Cholera is a water borne disease; people drank water from a street pump and some became sick. This type of logical connection was the starting point for Semmelweis. Concerned about the high incidence of child-bed fever (and the death of new mothers) he found that an obstetrics clinic run by men saw a much higher rate of the illness than another run by women. It emerged that the men frequently worked in post mortem examination rooms from where they would go directly to the delivery room, so spreading infection. Thomas Eakins’s picture The Gross Clinic shows the world to which Semmelweis’s investigations belonged: the surgeons wear street clothes and work with unsterilized equipment. Semmelweis’s diagnosis was right but his views were not immediately popular. His advice was eventually heeded but he died a pauper in a lunatic asylum.

In the health world, some of the greatest advances have come from prevention strategies. By requiring physicians in a Vienna hospital to wash their hands and instruments in chlorinated lime between autopsy work and treating patients, Ignaz Semmelweis saved untold lives-even by changing so small a detail of medical practice. George Albee, an American expert on prevention, concludes from this and other evidence that ‘no mass disorder affecting humankind has ever been eliminated or brought under control by treating the affected individuar. A logical conclusion to be drawn from this maxim is that early intervention holds the answer to many social problems.

One reading of the experiences of Snow and Semmelweis would suggest that their discoveries were made in a eureka-like flash. In fact, the advances followed careful observation of the possible mechanisms involved in disease transmission. The findings may seem obvious now but to those who believed cholera to be an airborne disease, or that medical men knew more than midwives, the results must have seemed hard to believe. And there are indeed a number of reasons to doubt the benefit of early intervention.

1 There is seldom a single cause of death, illness or social disadvantage, so even after the supply of diseased water had been cut or doctors began washing their hands, people continued to die in Broad Street and in the Vienna hospital.

2 Typically, a significant proportion of people put at risk of disease, say by drinking water carrying cholera bacteria or by having a baby delivered by a doctor with dirty hands, do not become ill. Something protects them from the bad outcome. That is how immunity to disease builds up and why no disease has managed to eradicate the human race.

3 There are many paths between exposure to disease, illness and recovery or death. The contribution removing a pump handle or improving standards of clinical hygiene may make to health outcomes will always be difficult to judge.

4 Largely ineffective as they may have been, some treatments saved some of those who succumbed to disease. Some women infected with puerperal fever by doctors during childbirth survived to raise their children. Half those developing cholera would have lived to tell the tale.

The characteristics of the Broad Street cholera epidemic

In the end, Snow and Semmelweis were proved correct but the doubters also left their mark. Albee’s maxim that ‘no mass disorder has ever been eliminated or brought under control by treating the affected individual’ is true enough but, with the possible exception of smallpox, neither has a mass disorder ever been eliminated by a single preventative strategy. On the other hand, several such strategies, combined with greater clarity about the nature of the problem being prevented, can make a significant difference to the pattern and volume of people succumbing to that problem, as the diagram on the right illustrates. Any strategy should be of this order:

1 Primary prevention, which means intervening with an entire population, for example everybody living in the vicinity of the Broad Street pump, can make a substantial difference, but it is best combined with the following components.

2 Secondary prevention to stop a problem getting worse than it might otherwise. So, inoculating those exposed to dirty water can bolster the immune system and increase resistance to the disease.

3 Still some people will succumb to cholera. Treatment by rehydration and antibiotics of those who have the disease will prevent deaths. This has been called tertiary prevention by many commentators; the term ‘intervention and treatment’ is preferred here.

4 There is action to minimize the damage those who have the disease can do to others. In this essay, the term ‘social prevention’ is used to describe such action. As will be seen, when it is transferred to children at risk of various social and psychological problems, social prevention becomes an important aspect of the preventative armoury.

5 Finally, there is better diagnosis so that the professional response is appropriate to the problem being treated, whatever the stage of its incubation. This has been fundamental to developments in the health world.

Changing the character of problems posed by a disease

Geoffrey Rose, The Strategy of Preventive Medicine, Oxford Medical Publications, 1992 0-19-262488-5

Snow and Semmelweis’s work is part of a pattern of insight that has enabled what might be termed social research requiring social change to make vital inroads into the task of improving health. Some would argue that social change has been the major contributor to the longer and healthier life that many in the developed world enjoy. But such comparisons are less important than the nature of the preventative activity. Is it better to offer a universal service aimed at an entire population or a specific intervention designed to bring an early benefit to those at greatest risk?

Connecting two powerful empirical observations the epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose makes an eloquent argument in favour of what he calls the population strategy of prevention. First he notes from the work of George Pickering that there is little evidence to suggest a sharp distinction between ‘health’ and ‘disease’. Using blood pressure as his guide, Pickering found a broad distribution of systolic blood pressure among the population, meaning that doctors must decide what is ‘high’ or ‘low’. There is not, as medical practice at the time might have implied, two groups, one with healthy and another with unhealthy blood pressure; the thresholds change as understanding changes.

Second, Rose finds from a series of inter-country comparisons that the extremes in any society appear to bear a strong relationship to the mean. Put more plainly, in a country where relatively large numbers of people have dangerously high blood pressure, the blood pressure of the whole population will be relatively high. Or, as the average intake of alcohol in the United Kingdom has risen, so has the proportion of alcoholics increased. From this he makes the observation that moderate and achievable change by the population as a whole might greatly reduce the number who have conspicuous problems.

This essay relies on available research evidence. The bulk of it tends by its construction to favour the high risk rather than the general population strategy. At the close we will revisit Rose’s arguments, but it is probably fair to say that for services for children in need we simply do not know enough to be able to argue strongly for one strategy against another.

Early intervention and children in need

Accurately representing the incidence of childhood and adolescent problems is fraught with difficulty. One reading of the research is that most people have been brought up relatively untouched by instability, family discord, delinquency or health and education problems. By another reading, significant proportions of children have problems in at least one of the areas just mentioned. As later pages illustrate, for some children these difficulties will interact and increasingly demand the attention of children’s services.

Living situation and environment

Most children live with two parents. Eight out often children on any one day live in a household headed up by two parents and seven of the eight live with both birth parents. Lone parenthood has become more common, so that around a fifth (19%) of children live with just their mother (18%) or father (1%). For every 18 lone mothers, seven have never lived with the father, one is widowed, six are divorced and four are separated. Only 50,000 or so out of the 11 million or more children in England or Wales cannot live with a relative.

Family and social relationships

There have been well documented increases in family discord and divorce. Nearly two in every hundred children each year endure their parents’ separation or divorce, meaning that a quarter of all 16-year-olds will have had this experience. But most children continue to get on reasonably well with their parents. The Isle of Wight study found that a quarter of boys and 9% of girls had difficulty communicating with their mother and the National Child Development Study found that nearly 90% of children get on well with their mother. Department of Health research estimates that three percent of children live in households that are low in warmth and high in criticism, that is where the home environment is reckoned to be damaging to children.

Not surprisingly, ideas about early intervention and prevention migrate quite readily from health problems to social problems and from difficulties experienced by whole populations to those that affect children in particular.

A proportion of children develop what can broadly be described as social and psychological problems. Social and psychological problems form a distinct group but they will frequently interact with physical ailments and, because their ramifications are often so varied, they may demand the attention of several agencies, including health, education, police and social services.

Services for children in need are constantly being exhorted to intervene earlier and to put greater effort into preventing problems arising in the first place. It is true that children can develop social and psychological problems at an early age and that, unattended, difficulties accumulate and interact. Children’s needs may become particularly noticeable when they start school but are most commonly evident in adolescence. As the text to the left illustrates, substantial proportions of children experience difficulty of some sort. These findings also tell us that substantial proportions of children emerge into adulthood not having experienced or at least manifested significant problems.

Generally speaking, the less serious the problem, the greater the incidence. Most children display conduct problems at some time and the majority of boys, as well as an increasing proportion of girls, break the law. Most children have rows with their parents and a significant proportion experience unhappiness bordering on depression. Getting on at school, getting the most out of education and finding a satisfactory job also pose difficulties for large groups of youngsters.

Serious problems in childhood are much rarer. Less than half of one per cent of children are unable to live with relatives; just three in a hundred live in family environments that have the most damaging long-term effects; one in 50,000 commits suicide. But without effective intervention, early or late, serious problems tend to coalesce and worsen, so that by the time a young person reaches 16, services for children in need can be faced ...