Over the past 20 years, the historian of contemporary economic policymaking has increasingly had to share his research agenda with the economist, the political scientist and the sociologist (cf. Britton, 1991; Hall, 1982; Runciman, 1993). In many ways this is to be welcomed, as it has opened up opportunities for more collaborative research projects between these disciplines – which some economic and social historians have long argued for (Wright, 1986).

Given that contemporary theorists of the state have begun to encroach on the preserve of the economic historian, it could be argued that contemporary economic history (at least of economic policy-making) has been displaced by another social science discipline. However, recent work by British political scientists on policy transfer and American political scientists on policy learning has demonstrated that there are new and exciting lines of research which require the combined attention of economic and social historians and political scientists. But what is policy transfer and policy learning, and how can they be applied to monetarism in the United Kingdom?

Policy transfer and economic policy shirts

According to a survey on the literature by Dolowitz and Marsh (1996a, p. 344):

Policy transfer, emulation and lesson-drawing all refer to a process in which knowledge about policies, administrative arrangements, institutions etc. in one time and/or place is used in the development of policies, administrative arrangements and institutions in another time and/or place.

They do not use the terms policy transfer and lesson-drawing interchangeably, unlike Rose (1993) who refers to the overall process by which policy or institutions are transferred as lesson-drawing. Although Dolowitz and Marsh initially played down the differences in terminology in their review article, more recently they have begun to shift from this view. As the discussion at the first annual Policy Transfer Conference made clear, although policy transfer and lesson-drawing are not mutually exclusive terms, they do refer to different processes (Oliver, 1996a).

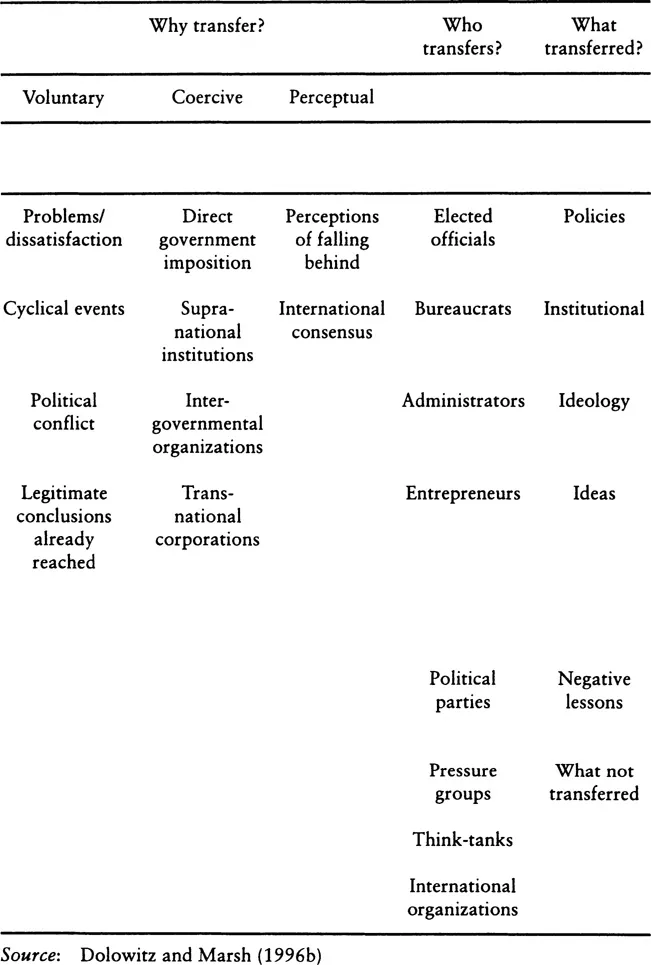

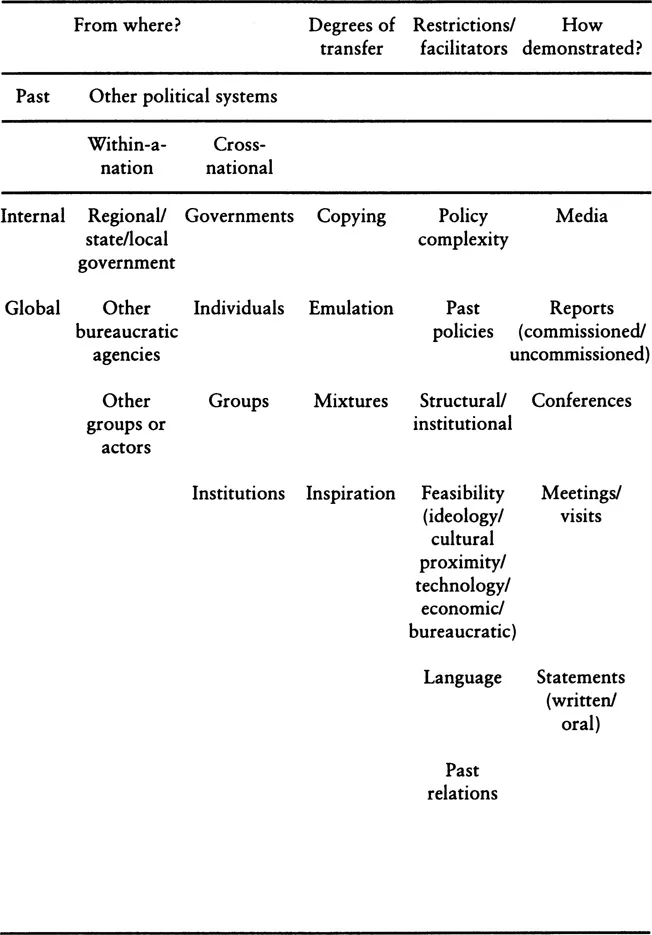

Table 1.1 presents a model of policy transfer. The first column (‘Why transfer?’) is divided into three, showing how the literature has categorized transfer studies. This tripartite division should not be seen as rigid. For example, Polsby (1984) has suggested that elections might force candidates to search for new solutions to existing problems, but this could be due to cyclical events at home (voluntary transfer) or because candidates are realizing that until they adopt new policies they will continue to fall behind economically and socially (perceptual transfer). Indeed, as will be seen, the introduction of monetarist policies by the UK government in the mid-1970s could combine all three explanations. There were problems with the existing Keynesian paradigm which led to voluntary transfer; the IMF required that the UK should set monetary targets, which was coercive transfer; finally, the international consensus (especially in the United States) began to shift to a more monetarist mode of thinking in the 1970s, which was coercive transfer.

However, it is far too simplistic to assume that the seven columns in Table 1.1 could account for the adoption and subsequent shifts in macroeconomic policy from the 1970s. Can it account for how the state, interest groups and other actors initiated shifts in policy? How does it address whether some of these agents and actors were more influential at shaping policy than others? More fundamentally, once policy has been transferred, can the existing literature explain how policy changes course and how lessons are drawn? The remainder of this section will briefly examine the three existing arguments in the political science literature which address why economic policies change course. The last argument will extend the discussion so that the wider questions raised above can begin to be considered throughout the remainder of the chapter.

The first explanation argues that macroeconomic policy is determined by the type of political party in government. The basis for this explanation follows the work of Hibbs (1977, 1982), who claimed to have found a link between ‘party stripe’ and economic outcomes in a study of 12 OECD countries during the 1960s. In short, he found that countries with higher inflation and lower unemployment rates were associated with ‘left’ parties while countries with lower inflation and higher unemployment were governed by ‘right’ parties. Similarly, work by Cowart (1978a, 1978b) in the field of monetary and fiscal policy and Castles (1982) in public expenditure concurred with Hibbs’s analysis.

Table 1.1 A model of policy transfer

The problem with this analysis, as Alt and Chrystal (1983, p. 116) have noted, is that the shift from Keynesianism to monetarism in both the United States and the United Kingdom in the 1970s happened during a time when there was a ‘left’ party in government. Moreover, Schmidt (1982) has challenged the empirical validity of Hibbs’s work and could find little support for the link between party incumbency and the trade-off between unemployment and inflation for the 1970s.

The second explanation, the PBC, argues that governments shift macroeconomic policy according to the date of the next election. In the run-up to an election, governments will follow a reflationary (‘Keynesian’) policy, but after being re-elected they will adopt a deflationary (‘monetarist’) approach. The work of Nordhaus (1975) and Tufte (1978) is the most prominent in this field, although both analysts disagree on what governments want to deliver to voters. Nordhaus argues that the aim of a pre-election expansion is specifically to achieve a full level of employment, while for Tufte, governments aim to produce a fall in unemployment and a rise in real disposable income.

Critics have pointed out that this approach also suffers from empirical limitations (Alt and Chrystal, 1983, p. 125; Whiteley, 1986, p. 82), leading one academic (Lewin, 1991, p. 63) to conclude that ‘research of the 1970s and 1980s gives only very weak support to the theory of political business cycles if, indeed, one can speak of support at all’. The PBC theory also presupposes that politicians assume that voters have short memories and no expectations, so that ‘voters are expected to make their choice at the ballot-box on the basis of what has happened to them over the last few months before the election’ (Hood, 1994, p. 65). This assumption, that the electorate do not learn from the actions of politicians, is tenuous as Nordhaus (1989, p. 4) has recognized. Moreover, although the PBC is more capable of explaining ‘why “left” governments as well as “right” ones should sometimes adopt “monetarist” macroeconomic policies’ (Hood, 1994, p. 67) than the political incumbency approach, both explanations tend to suffer from taking too narrow a perspective. As Thompson (1994, p. 28) has argued:

... both accounts are too heavily focused on the ultimate ends of policy, particularly unemployment and inflation. As a result, they have little to say about governments’ interests in relation to the means by which those ends are reached ... macro-economic policy concerns choices about means. Once this is accepted, it becomes a highly dubious proposition to suggest, for example, that ministers seek to accommodate voters’ preferences on whether inflation should be controlled by monetary or fiscal policy.

The third explanation in the literature examines the way in which institutional structures shape macroeconomic policy. Over the last two decades, political scientists have offered alternative theories on how public policy is formulated (Caporaso and Levine, 1992; Krasner, 1984; Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth, 1992; Wilensky and Turner, 1987). It is possible to bifurcate these analyses of the state into two: on the one hand there is an approach which has been labelled state-centric, while the other approach is identified as state-structural (Hall, 1993, p. 276).

Those who argue from a state-centric point of view (Krasner, 1978; Nordlinger, 1981; Sacks, 1980) tend to emphasize the autonomy of the state from interest groups, political parties and outside actors in the policy-making process. The last 25 years have seen an enormous growth in this literature, influenced by the work of Hugh Heclo (1974). In a pioneering study which examined social policy in Britain and Sweden, Heclo argued that the policy-making process could not be satisfactorily explained by the electoral process, by interest groups or by socioeconomic developments: ‘Forced to chose one group among all the separate political factors as most consistently important... the bureaucracies of Britain and Sweden loom predominant in the policies studied’ (Heclo, 1974, p. 301).

The opposite to this view is the state-structural approach (see Katzenstein, 1978, 1985; Skocpol and Ikenberry, 1983; Weir and Skocpol, 1985) which is ‘less concerned with the relative autonomy of state institutions than with the effects of different decision-making styles in terms of degrees of corporatism’ (Hood, 1994, p. 69). As Krasner (1984, p. 223) has noted, from the late 1950s until the mid-1970s, ‘political scientists wrote about government, political development, interest groups, voting, legislative behaviour, leadership and bureaucratic politics, almost everything but “the state’“.

While the terms ‘state-structural’ and ‘state-centric’ are unfamiliar in the lexicon of the economic historian, some of the ideas which are central to these arguments have been hotly debated among economic historians in a wider context, such as the role of interest groups and institutions (North, 1984; North and Thomas, 1973; Olson, 1982). Moreover, common to both the economic historian and the political scientist is lesson-drawing. As Heclo (1974, pp. 305–6) acknowledges:

Politics finds its sources not only in power but also in uncertainty -men collectively wondering what to do. ... Governments not only ‘power’ ... they also puzzle. Policy-making is a form of collective puzzlement on society’s behalf. ... Much political interaction has constituted a process of social learning through policy.

As will be discussed below, social learning draws on both the state-centric and state-structural approaches. Originally deployed by those working in cybernetics, organization theory and psychology (Argyris and Schön, 1978; Bandura, 1977a, 1977b; Steinbrunner, 1974), social learning was discussed by Etheredge in his two accounts (1981, 1985) of governmental learning. Yet until recently, social learning was presented in the social science literature in a sketchy form in contrast to the model developed in organization theory and cybernetics (see Ellison and Fudenberg, 1993).

Thus although the published research among political theorists was moving the concept of social learning towards a mainstream tool for social scientists, a full-blown model had not been developed or applied satisfactorily to a specific empirical setting and the debate was in need of a fresh stimulus. The breakthrough came in two stages and from the same source.

The social learning model

The first breakthrough came when Peter Hall (1990) contributed a chapter to a book which examined the role of social scientists, policymakers and the state. In this chapter, Hall (1990, p. 9) labelled ‘the overarching framework of ideas that structures policy-making ... a policy paradigm’. With explicit references to the work of Thomas Kuhn (1970), Hall argued that Kuhn’s analysis had a considerable validity within the social science sphere. Hall gave a new twist to the ‘growth of knowledge’ theory and takes the debate further than Dow (1985) or Mehta (1977), if only because he stresses the sociological and political issues associated with policy paradigms, rather than just the pure economics of paradigms.

Secondly, and more importantly, social learning was discussed at length in Hall’s (1993) seminal article in Comparative Politics. In this article, Hall transported social learning from a social psychology theory to a social science model. He did so by doing four things.

Firstly, he was able to show how contemporary theorists of the state had moved tantalizingly close to forming a model of social learning by identifying three central features from the state-centralists and state-structuralists. First, policy at time-1 is affected by policy at time-0: in other words, policy-makers respond to either past successes or failures in policy and conduct future policy with regard to policy legacies (Sacks, 1980; Weir and Skocpol, 1985). Second, those who are determining policy are experts within their fields. Heclo’s (1974, p. 308) model of Swedish and British bureaucracies demotes the influence of the politician and promotes the role of the specialist in detailed areas of policymaking. Third, social learning emphasized that governments act independently from societal pressure, to the extent that many interest groups and political parties play a very small part in developing policy (Heclo, 1974, p. 318; Sacks, 1980, p. 356).

Secondly, Hall provided the first explicit definition of social learning for the social sciences in which social learning is ‘a deliberate attempt to adjust the goals or techniques of policy in response to past experience and new information. Learning is indicated when policy changes as the result of such a process’ (Hall, 1993, p. 278).

Thirdly, Hall stated that policy-making should be seen as a process that usually involves three central variables: goals that direct policy in a certain area; the policy instruments used to attain those goals; and the precise settings of these instruments.

Fourthly, if these goals, instruments or instrument settings are altered, then there are four Orders of change’ which follow. First-order change occurs when the levels of the basic instruments of policy are altered. Second-order change is denoted when the instruments of ...