eBook - ePub

Housing: Participation and Exclusion

Collected Papers from the Socio-Legal Studies Annual Conference 1997, University of Wales, Cardiff

David Cowan, David Cowan

This is a test

Share book

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Housing: Participation and Exclusion

Collected Papers from the Socio-Legal Studies Annual Conference 1997, University of Wales, Cardiff

David Cowan, David Cowan

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Published in 1998, current themes in housing are explored in this collection of papers. The gamut of issues surrounding participation, such as tenant participation or decision-making participation, together with the forces leading to exclusion, such as in relation to ethnic minorities, are examined. The book will be relevant to all those in the housing movement together with those working in related disciplines.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Housing: Participation and Exclusion an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Housing: Participation and Exclusion by David Cowan, David Cowan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Housing & Urban Development Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 Bringing Tenants into Decision-Making

Introduction

Over the past two decades, as public funding for housing declined, Conservative central government policies favoured greater involvement in management by tenants and made some local authority funding for estate improvement conditional on their involvement. While in some localities the process has advanced further with the introduction of innovative management partnerships between landlords and tenants, everywhere the tenor has been shifting from viewing tenants as passive recipients of landlord bounty to customers or partners. This movement has not been confined to local authorities. Within the housing association movement, some associations have taken tenants onto management committees and have invested in training tenants to make them more effective participants. Against this background of gradual shifts in culture there have been major urban regeneration mechanisms such as City Challenge and Single Regeneration Budget through which tenants have been renamed as stakeholders and have been called upon to become decision makers alongside local authority officers and business people. This chapter explores the legal, managerial and policy changes that have contributed to this growth in participation and finally considers the potential of tenant participation to be a vehicle for social inclusion.

Defining Participation

The discussion begins with the vexed question: what is tenant participation? In the late ’80s alone the following all seemed possible definitions:

the involvement of tenants in decisions which affect their housing (Community Development Housing Group, 1986);

It means devolving real control over policy and resources at the local level, leading to programmes which are better targeted and more suited to tenants requirements and indeed resulting in a strengthening of local responsibility and democracy (Lord Ancram, 1986, quoted in Grayson, 1996, p. 55);

A two-way process involving sharing of information and ideas, where tenants are able to influence decisions and take part in what is happening (IoH/TPAS, 1989, p. 19);

The councillors defined tenant participation as providing tenants with information about council policy, the majority of staff thought it meant consulting with tenants before decisions were made and the tenants saw it as being involved in decisions about housing policy and the provision of the service (Platt, Piepe and Smyth, 1987, p. 1);

… we use the terms consultation and control. Other phrases are trotted out in writings on this subject, such as ‘participation’ or ‘involvement’, but it is not always clear what is meant by them. Control is used … to refer to the actual structural right to take a decision and is a stage beyond consultation (Bartram, 1988, p. 9).

From this we might agree that ‘participation’ is a slippery and essentially dynamic concept. It raises questions of power, ideology and influence in public policy-making and service delivery. ‘Its shifting meaning reflects the varying values and interests held by different stakeholders and the influence which they can wield in establishing their preferred definition’ (Furbey, Wishart and Grayson, 1996, p. 251).

The history of tenant participation in the UK is the story of how values have shifted so that we have moved from consultation to control, at least, in terms of what is possible in law and for which good practice models exist. This discussion begins by sketching in the major legal changes that have contributed to the increase in tenants’ power.

The Legal Framework for Participation in Management

The interest of government and the housing profession in tenant participation began in the late 1950s. The Central Housing Advisory Committee (1959) advocated the benefits of a better relationship between tenants and local authorities. In 1968 a government circular on council rents recommended greater tenant consultation and in the same year a private member’s bill was introduced which proposed setting up an advisory committee with tenant representation in each local authority. Though this failed, many local authorities were responding through the introduction of tenants’ charters to the general groundswell of opinion that, as landlords, they should be less remote. This concern may have sprung from the 1974 radical restructuring of local government which created large bureaucracies with all their attendant problems. It may also be that the growing scepticism over the architectural solutions of ‘experts’ (Ronan Point, the dissatisfactions with tower blocks and the dinosaur estates heavily criticized by Alice Coleman, 1988) created a space where the voice of everyday experience could be heard. It was in the late ’70s that the demand for participation came to the fore, mobilizing around the issue of collective and individual rights for tenants. There was pressure from below by tenants who had grown in power through the rent strikes of the ’70s. Support for tenant participation from above came as central government sought various ways to promote tenant involvement (Furbey et al., 1996). Motivations were not the same. Kay, Legg and Foot (undated) put together a powerful argument that economic pressure was the catalyst for cross-party support of the introduction of tenants’ legal rights. They argue that the recession and the implications for public spending meant that the problems of housing shortage and the quality of existing stock could no longer be addressed by large injections of public money. Giving tenants greater rights, central government felt, would increase their individual sense of responsibility, increase collective satisfaction and improve the effectiveness of housing management. Tenants’ rights, then, were to be a panacea in the face of fewer capital schemes, pressure on rents and undoubted, future discontent from tenants.

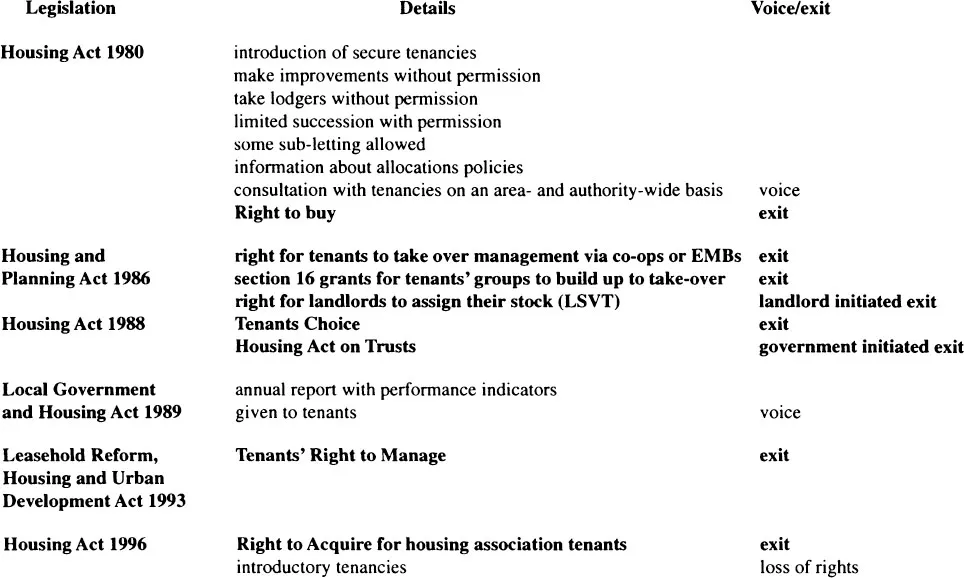

The National Tenants Organisation, established in 1977, proposed a charter of rights, part of which, in the following year, was set within the Labour government’s Housing Bill introduced in 1979. The coming to power of a Conservative government in that year saw most of these rights enshrined in the Housing Act 1980 with the addition of the first of the Conservatives’ exit strategies: The Right To Buy. Thereafter, legislation came thick and fast with every piece of housing legislation giving extra rights to tenants and seeking to alter the power relationship between local authority landlords (as opposed to housing association landlords) and their tenants. Figure 1.1 outlines the main points of the legislation as it touched upon tenants’ rights. It also attempts to analyse these according to whether they give increased rights; voice (that is a channel or arena for tenants to express dissatisfaction and create change from within); or exit routes (whereby tenants might express their dissatisfaction by moving from one landlord to another) (Hirschmel, 1970; Jensen, 1995). The figure also sets out whether these new options apply to individual tenants or to tenants collectively.

Figure 1.1 Legislative approach to tenants’ involvement in housing management

The Housing Act 1980, in the main, gave tenants basic individual rights surrounding their contract with their landlord. However, there was also the right to be consulted on an area and authority wide basis which was important in bringing the landlord into contact with a collective voice on area improvement issues which might affect many households, such as children’s play facilities, car parking, and landscaping. However, one of the most important collective concerns for tenants – the level of rents – was specifically excluded from consultation though in practice some local authorities have gone beyond the law and consulted with tenants on rent rises (Bartram, undated).

The main point for which this Act will be remembered is the introduction of the Right to Buy, which can be described as an individual exit route though it is doubtful whether any purchaser has bought because of a desire to escape local authority control (Murie, 1995). While the Act gave a right it did not confer equal access to it for council tenants. Many of those now in the social housing sector lack the waged income to purchase (Gilroy, 1994). Many others live in undesirable property in areas which have become war zones, where the concept of making such a major personal investment would be economically unsound. Clearly such an exit mechanism only works for a particular cohort of tenants. Other routes were needed for those without economic power.

The Housing and Town Planning Act 1986 gave local authority landlords the right to assign the management of their stock to an agent and through this came two different exit routes. The first of these was the opportunity for tenants as a group to become the agent and take over the management of their estates through a tenants’ management co-op. A new middle route also emerged at this time called an Estate Management Board, a legally constituted partnership between officers and tenants to jointly decide policy and its implementation on a given estate. This new model acknowledged the desire of many council tenants to stay with the local authority but at the same time to break away from the monolithic bureaucracy (Bell, Bevington and Crossley, 1990, p. 97). For the first time, training and development grants were made available for tenants’ groups through section 16 of the Housing and Planning Act 1986 but these were targeted only at those who were looking to take over stock or management of stock. They were not intended to be a general pump priming fund to empower tenants to come together as a collective in a dialogue with their landlord. Central government was interested in encouraging ‘exit’ in any form but not ‘voice’.

The second exit route was the opportunity for local authorities to seek a ‘voluntary transfer’ of all their housing stock to another landlord, usually a housing association. While local authorities, at first, overlooked this, it became more attractive as central government revealed the main planks of the 1988 Act which many housing providers saw as the hammer which would finally fragment local authority housing. These authorities, concentrated at first in the Conservative held southern district councils, began to set up housing associations and divest their stock to them (known as Large Scale Voluntary Transfer or LSVT). In this process tenants had the right to be consulted and the right to vote for or against the proposed switch. Early ballots saw a largely negative response from tenants but as the financial implications of the 1989 Local Government and Housing Act became apparent, with indications of higher rents and lower investment, more tenants saw the wisdom of moving themselves and their homes into the housing association sector (Cole and Furbey, 1994). It would be fair to say that Conservative central government was taken by surprise (though no doubt delighted) by this windfall increase in their primary housing objective — to dismantle the power of local authorities by reducing the scale of their property holdings. In practice, the mechanism merely operated to transfer housing stock from one bureaucracy to another.

An added impetus to local authorities to talk with their tenants was given by the Housing Act 1988 which created two new exit options: Tenants’ Choice and Housing Action Trusts (HATS). Tenants’ Choice gave local authority tenants only (not housing associations) the right to choose to replace their landlord with another (such as a housing association or a commercial company) or to become more directly involved in the running of their property by taking on the ownership and management (tenants’ cooperative, neighbourhood housing association, tenant companies).

While presenting an exciting range of choices on paper, few tenants’ groups felt motivated enough or dissatisfied enough to seek out alternative landlords and only two estates (both in Westminster) went down the route of tenant buy-outs via tenants’ companies and neighbourhood housing associations. The dismal lack of response ultimately caused the tenants’ choice mechanism to be ‘mothballed’ after only two years and repealed in the Housing Act 1996.

The announcement that Housing Action Trusts would be set up in estates around the country chosen by central government was greeted, not with apathy, but with great hostility. In these particular neighbourhoods, it was proposed that the local authority stock would be transferred to the ownership of a quango which would independently make decisions about improvement and management. Animosity was fuelled by the arrogance of government ministers who denied tenants the right to vote on the grounds that their understanding of the policy was incomplete. Finally forced to concede a right to vote on the introduction of each HAT, central government was caught unawares by the collective anger and unanimous rejection of the proposals (Woodward, 1991).

These two exit routes were, from government’s point of view, failures to hit the target. Tenants did not flock to change their landlord; indeed, they demanded the right to stay. However, from the perspective of the tenants’ movement, the major retreat by central government on Housing Action Trusts was a great victory for collective action. A number of tenants’ federations, like those in Kirklees and Sandwell, were developed during this period of campaigning, as was the Estate Management Board in Belle Isle in Leeds and hundreds of other tenants’ associations and federations. Hulme tenants having successfully defeated the HAT proposal for their estate forced major concessions and changes to the redevelopment and future management of their notorious deck access estate (Grayson, 1996).

In fact the Housing Corporation had foreseen this reaction and had suggested that tenants use the legislation, not as an exit route but as a mechanism for increasing their ‘voice’. It is interesting to note that the Housing Corporation imagined that the opportunity for power through Tenants’ Choice would galvanize tenants while the true catalyst was their disempowerment through Housing Action Trusts.

It may be that after you have considered the options under Tenants’ Choice you come to the conclusion that you want to stay with the council but want to try to work with them ...