CHAPTER ONE

Is Knowing the Tax Code All It Takes to Be a Tax Expert? On the Development of Legal Expertise

Garry Marchant

University of Connecticut

John Robinson

University of Texas at Austin

Is a legal expert someone who knows the law? Knowing the law would seem to be a good starting point, but clearly, when choosing a lawyer, we look for much more than this. After all, clients want a lawyer who can win for them, but winning involves much more than knowing the law. One cannot rely on rules alone, because in the law rules such as statutes and regulations are insufficiently well defined, and thus the legal expert must resort to other sources of legal authority—primarily previously decided authorities to elaborate and explain the application of the law. This is not undesirable, because the law must be fluid and adaptive, bending as social and political circumstances demand.

As Judge Spaeth points out in the companion chapter to this one (chap. 2), no matter how codified a particular area of the law becomes, understanding and analyzing the legal principles relevant to a particular client’s situation remains dependent on tacit knowledge acquired through experience and observation. This dependence on tacit knowledge is true, even though the profession tries to minimize its role. There are courses at law schools on trial advocacy, legal research, and legal reasoning. These courses ultimately fall short, because there is no agreement even among the most experienced practitioners as to the single best way to analyze a problem or develop a legal argument. And so, in the end, the legal profession, like most other professions, relies on the ad hoc nature of experience to guide junior members of the profession in the development of their expertise and competence as legal practitioners.

Legal expertise is then defined as the ability gained from experience to understand and apply the rules, statutes, and legal principles to a novel problem by using previously decided authorities to build a legal argument. The lawyer must be able to determine the critical factors from the facts and issues presented by the client. Then they must build an argument, with the strongest possible support for the client. To win, the argument should be based on all available authority that supports the client’s point of view and counters an opposition’s point of view, without giving the opponent any opening to counter the original argument. Knowing the law is only a small part of this process; the expert lawyer must also be able to rank available precedent as to strength and appropriateness and identify and counter an opponent’s arguments. Legal reasoning is thus by nature dependent on the creative use of analogy to weave arguments that apply a favorable legal principle to a new and often diverse set of circumstances.

The legal environment makes it difficult to develop these skills and knowledge. First, only a small percentage of the legal arguments prepared by lawyers ever makes it to court. The courtroom is the only objective arbiter of legal argument, and the only place where the strength of an argument is tested, its weaknesses and strengths identified, and the outcome observed. But, of course, clients would prefer disputes be resolved without resorting to the court, so often disputes are negotiated and settlements are made. Such resolution may occur partly to avoid the cost of further conflict or based on the strength of the relative arguments of the opposing counsel. Lawyers must therefore rely not on objective outcome feedback, but on peer review, for much of their practical education. Additionally, the adversarial nature of the legal system focuses lawyers on winning for their client—on being an advocate. Although this may seem like a desirable systemic attribute, playing the role of an advocate focuses practitioners’ thinking on supporting their client and thus may distract them from considering alternative points of view and possibilities. Thus, the adversarial process may act to limit them to the range of possibilities in developing legal arguments. Perhaps the outstanding lawyer is the one who looks beyond the authority that supports his or her client’s point of view and, in doing so, discovers authorities that enrich and enhance his or her argument in ways unanticipated by the opposition.

The tacit nature of legal expertise has significant implications for the education of legal professionals, the management of a legal practice, and the quality of legal services. One of the key elements of legal expertise is the ability to look at a sequence of authorities and identify the principle the court has in mind based on their opinions. Legal education must focus on the development of inductive skills rather than deductive skills. Evidence suggests that using authorities to allow for the induction of principles is effective particularly when the authorities are atypical rather than typical exemplars. Also, in managing a legal practice, one of the most critical decisions a partner makes is which case to give to which associate, and associates are painfully aware of the resulting opportunities to learn and develop their expertise as a result. Because learning cannot occur frequently from feedback, peer review is used as a mechanism both for ensuring quality and as the means for mentoring and guiding the inexperienced lawyer.

IS A LEGAL EXPERT ONE WHO KNOWS THE LAW?

In legal settings, rules such as statutes and regulations are often ambiguous or indeterminate in their application to fact situations (Hart, 1961). This characteristic open texture of legal rules is useful, because legal rules must be fluid and adaptive so that they may survive for many years. In order to apply a rule to a specific situation, a lawyer must use a previous decided case. Lawyers have no choice but to rely on analogy to forge their position and interpretations. Legal rules are not typically well defined, nor are there intermediate rules that define the elements of these legal rules well enough so that a lawyer can determine the use of a general rule in a specific fact situation (Ashley, 1988). Even in highly codified areas such as taxation, the expert must resort to tax court authorities and IRS rulings to interpret and apply the code. Knowing the details of the tax code is insufficient to solve client problems; the legal expert must interpret how the code applies for a given fact situation by looking at how it and other similar or related provisions have been interpreted.

For example, Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 1033 allows nonrecognition of gains on certain involuntary conversions if the proceeds of the conversion are reinvested in “similar” property. To determine the scope of what constitutes “similar” property, the tax expert might look at court opinions that decide authorities under the auspices of IRC Section 1031, which allows deferral of gains and losses when property is exchanged for “like kind” property. An analogy between these two statutes is possible, because both statutes allow deferral if property is replaced with equivalent property. Thus, even the diverse and highly codified area of tax law abounds with potential applications of analogy. It is the area of taxation to which we confine the following discussion and draw examples, because it is the ideal extreme case, so codified and practiced in such diverse settings by lawyers and nonlawyers alike that to the person on the street it is the area of the law least likely to depend on tacit knowledge. Yet, as we show, an effective tax practice is very much dependent on tacit knowledge for analysis, judgment, and the development of legal expertise.

Legal Reasoning and Analysis in the Tax Domain

The legal task environment, and particularly the area of taxation, is rule based. Statutes are fixed by legislative enactment, but their application is an open question based on an understanding of the language used in the statute. Thus, there are two types of tax authorities that may be brought to bear in legal reasoning:

- Tax statutes.

- Interpretations and applications of the statutes in Treasury Regulations, court decisions, and IRS rulings.

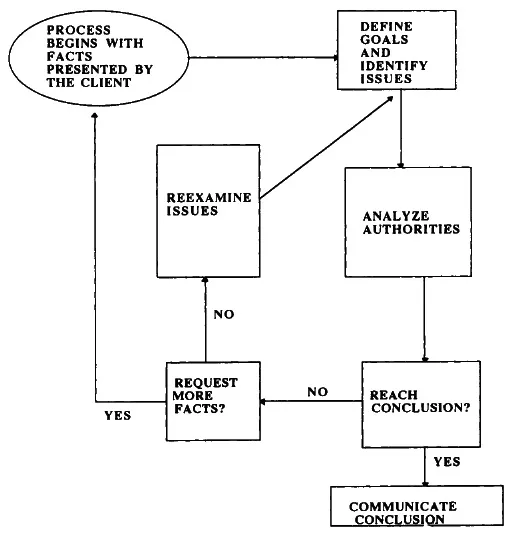

The analysis of these authorities leads to the interpretation of the statutes and the selection of an appropriate tax treatment. The method of analysis and reasoning is an iterative procedure (see Fig. 1.1), in which the practitioner identifies the goal or objective, evaluates the available authorities, and returns to request more facts or identify new issues before reaching any conclusions (Marchant et al., 1989).

FIG. 1.1. The process of legal reasoning.

The legal reasoning process comprises four steps (Buchanan & Headrick, 1970). In the first step, the practitioner must develop and evaluate the goal of the analysis based on the information provided by the client. The second step involves the use of other instances to identify the relevant facts in the client’s story and to rank the importance of the issues. The third step is the selection of the appropriate treatment from the set of statutes and authorities that can be applied to a fact scenario. Finally, the fourth step involves the use of analogy: When, as is frequently the case, a situation with identical facts cannot be found, an analogy to either the facts or the treatment is used (Buchanan & Headrick, 1970; Gardner, 1987; Levi, 1949; MacCormick, 1978). Thus, legal reasoning is dependent on the use of analogy, because analogy is the basis for comparing and evaluating authorities and thereby interpreting and applying the statutes. Two general strategies can be identified in the tax domain that utilize these four basic steps of legal reasoning. These strategies—compliance and planning—define the parameters of the cognitive processes inherent in legal reasoning in the tax domain.

The Compliance Strategy. The first strategy, compliance, emphasizes the interpretation of both facts and the relevant law for the benefit of the client (Buchanan & Headrick, 1970), and consists of the following basic steps:

- Specify an objective.

- Identify relevant facts.

- Search for authorities that apply a rule that leads to the desired consequences, given the identified facts.

- Evaluate and compare the facts and legal issues in these authorities. Test the facts against the given application of the rule.

- Accept, reject, or modify the application of the rule.

This process is appropriate in the compliance setting, where the transactions are already completed (Black, 1981).

Consider the following example of a compliance problem, which illustrates the inductive framework of legal reasoning in the tax domain. Suppose that the practitioner is presented with a client who has made support payments to a spouse before the issuance of a divorce decree. Depending on his or her expertise, the practitioner may draw on his or her knowledge of the tax laws to identify the relevant issue as the deducibility of the payments as alimony under IRC Section 71. However, because some payments preceded the issuance of the divorce decree, the practitioner may have found it necessary to consult the tax authorities to ascertain if all of the payments qualified for deduction. As the practitioner analyzed the authorities, he or she may have also found it necessary to inquire about additional facts, such as whether any written agreement existed prior to the issuance of the divorce decree and whether the client was living apart from his spouse. All of this information is sufficient to establish an immediate goal of generating an opinion as to the proper tax treatment of alimony paid before a divorce decree has been issued.

The facts and the practitioner’s knowledge may not provide the practitioner with enough information for the specific type of situation to be identified and an opinion proposed. The practitioner’s knowledge and the facts provided by the client form a basis for the practitioner’s mental representation of the current problem. This knowledge representation forms a mental model of the problem, which the practitioner uses to move toward a solution. Mental models are made up of bundles of knowledge organized into sets of associated knowledge categories at various levels of abstraction. These categories form expectations about the client’s scenario based on the assumed relationships between categories. These expectations can be over-ridden by specific information, but otherwise they provide the best guess as to the probable solution to the problem (Minsky, 1975). The categories that represent the practitioner’s current mental model might include the general-level category “divorce and alimony,” a midlevel category relating to “separation agreements,” and the active goal of “determining the deductibility of the payments.” No specific level information has been identified yet, and so none is included in the mental model of the current legal problem. This representation is a subset of the legal professional’s domain-specific knowledge. Domainspecific knowledge of the legal professional would include basic concepts, procedural skills, and contextual attributes (Anderson, Marchant, & Robinson, 1989), and forms a critical component of the professional’s expertise (Chiesi, Spilich, & Voss, 1979).

For the purpose of this example, assume that there are four possible specific categories that might lead to a solution: oral agreement, written agreement, retroactive decree, and no agreement. In this case, the practitioner’s preferred interpretation of the facts is that a written agreement exists, because the client may then deduct the payments. But this cannot be confirmed, given the current state of the practitioner’s knowledge. This current state is identified by two conditions. The first condition is that there are predecree support payments, and the second condition is that no solution can be confirmed. These conditions combined lead the practitioner to request more information about the agreement from the client. For the purpose of illustration, assume that the situation is relatively unambiguous and that the proper tax treatment is straightforward once the type of agreement is identified. The client might indicate, in response to the request for more information, that the agreement was oral and that no written document existed prior to the issuance of the divorce decree. This response results in additional input from the client that gives the specific category of oral agreement, the support necessary for its inclusion in the practitioner’s mental model of the problem. Because this specific category is goal relevant, the lawyer’s mental model now moves toward problem resolution.

The inclusion of the goal-relevant category, oral agreement, prompts the revision of the current mental model based on the new knowledge represented by the features of that category. The combination of this knowledge with the goal of generating an opinion about the proper tax treatment of the alimony leads to the generation of the response that alimony is not deductible. The combination of the generated response and the goal-relevant category also leads to the production of expectations about future outcomes, such as that the response will lead to higher taxes or will lower the risk of an audit by the IRS. These expectations could also be revised, based on observed future events, such as an IRS audit. This process allows professionals to learn and revise their rules and beliefs on the basis of outcomes.

The Planning Strategy. The second basic research strategy, emphasizing planning and risk assessment, concerns the recommending of actions that satisfy the client’s goals while avoiding unfavorable consequences (Buchanan & Headrick, 1970). The three stages of the planning strategy are:

- Identify possible actions for client.

- Match facts and generalizations from authorities with the possible fact scenarios generated in the first stage, and determine potential risk.

- Predict the likelihood of success for possible fact scenarios, and rank order alternatives.

This strategy varies from compliance in that the facts are controllable over some range of alternatives. These alternatives meet a broad set of objectives, including business objectives as well as a favorable legal outcome. The planning strategy corresponds to the tax planning process, which is described by Black (1981) as “an open fact situation where tax practitioners assess alternative tax strategies for structuring contemplated events” (p. 301).

Consider the following example of an open fact tax research problem. Suppose that the practitioner is approached by a client who intends to incorporate his or her existing business by contributing the assets of the business to a new corporation in exchange for stock. Depending on his or her expertise, the practitioner may suggest the issuance of debt in addition to the stock or, alternatively, the election of Subchapter S status. The practitioner recognizes the potential of double taxation of the business’s profits and assumes that the client wishes to avoid it. The principal advantage of debt is that the payment of interest to the client would be deductible by the corporation, whereas dividend payments are not. A Subchapter S election more or less avoids the corporate tax.

In terms of cognitive processes, the appropriate knowledge is retrieved based on the scenario presented by the client. The client-provided scenario leads the practitioner to identify as the relevant goal the maximization of after-tax income within the corporate form. This generated goal then directs, within the practitioner’s mental model, the search for goal-relevant knowledge and the generation of plausible alternatives. Based on the goal of maximizing after-tax income, the tax expert will retrieve the various knowledge categories related to incorporation. The expectations related to these categories will provide a basis for judgments as to taxability, depending on the alternative scenarios for incorporating a business. This set of expectations for incorporating a business includes a number of plausible alternatives, including Subchapter S election and the use of debt in the capital structure. Once a goal-satisfying alternative is found, the practitioner’s mental model will generate expectations, based on the identified alternative, that will form the tax advice to the client.

Assume that a Subchapter S election is the strongest goal-relevant alternative and forms the basis of the tax practitioner’s mental model used to generate expected consequences of incorporation. The use of the Subchapter S election category allows the practitioner to conclude that this alternative minimizes taxes and thus meets the goal of maximizing after-tax income of the business. The practitioner will then use the current mental model, based on his or her knowledge of a Subchapter S election and the goal of maximizing the after-tax income of the business, to generate a set of expectations as to the taxability of this corporate form and the constraints imposed by using this election. This planning scenario is communicated to the client as the best alternative given the provided information.

The tax practitioner’s current knowledge could be modified if additional information were provided by the client. Suppose that the client indicated that he or she wished to issue a second class of stock to relatives. This additional information would necessitate a revision of the practitioner’s mental model, because one of the constraints in electing Subchapter S is that the corporation have only one class of stock [IRC Section 1361(b)]. The practitioner will search at a more detailed level to ascertain under what circumstances a Subchapter S election is consistent with the existence of two classes of stock. Relevant authorities and cases are identified, so that the mental model may be revised to fit the new goal. The appropriate authority is selected through a process of rule competition. Rule competition is a process by which knowledge is filtered, so that only the knowledge that best fits the client’s scenario is added to the mental model of the problem. The authorities selected are determined by their relative strength, based in great part on how often they have been used in the past, and by the degree to which they match the authority to the client’s scenario. The selection of an appropriate authority requires the comparison and evaluation of existing authorities with the presented or prospective facts. In the situation where no authority is specifically on point, the practitioner must resort to analogy to reach a conclusion. In the legal domain this is by far the most frequent occurrence, and so the institutionalization of analogy in legal reasoning as the rul...