eBook - ePub

Feminist Review

Issue 37

The Feminist Review Collective, The Feminist Review Collective

This is a test

Share book

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Feminist Review

Issue 37

The Feminist Review Collective, The Feminist Review Collective

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1991. This issue of Feminist Review has a special focus on women's attitudes to religion and the attitude of religions to women.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Feminist Review an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Feminist Review by The Feminist Review Collective, The Feminist Review Collective in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

REVIEW ESSAY:

Alert for Action

Women Living Under Muslim Laws Dossiers 1–6

This article attempts to show the invaluable role that the Women Living Under Muslim Laws dossiers have come to play in our political work in Southall Black Sisters (SBS). They are produced and published by the French-based Network of Women Living Under Muslim Laws and encompass a variety of views originating from different ideological and political positions. We do not necessarily agree with all the perspectives reflected in the dossiers, but the Network and its unflinching support have become an essential part of our political struggle.

Women Living Under Muslim Laws first began to send us written materials about their work and activities soon after SBS and other women set up Women Against Fundamentalism (WAF). Some of us skimmed through the dossiers which were then filed away, together with the wealth of other information we had received on a number of issues connected to the WAF campaign. We did not really think about them again until we were forced to by the predicament of Rabia Janjua. Women Living Under Muslim Laws and their dossiers then took on a significance that went beyond our expectations.

Rabia Janjua was first referred to SBS by a health visitor from Hounslow. We were informed that she was in a very depressed state, having just given birth to a second son. Her husband had left her and she was facing a number of problems. She spoke no English. She was unable to come to our centre, so we visited her. She was living in a large bed-and-breakfast hotel in Hounslow. We met an extremely haggard-looking woman who was distressed and anxious about her circumstances. It was very difficult to understand and unravel her situation. She talked about the immigration authorities wanting to remove her and of her husband’s violence. Yet she did not have in her possession a single official document to help us understand what was happening. All her papers, she said, had been retained by a couple who were assisting her and making representations on her behalf to the Home Office.

We learnt that Rabia had been raped in Pakistan by her now enstranged husband. She had been forced to marry him because she was afraid that she would not be believed by her family or the authorities. They chose to run away but were eventually found and charged with Zina (unlawful sex). They had been detained for a month and were awaiting trial when they were granted bail. They jumped bail, however, knowing that they would face imprisonment and public flogging as punishment. As her husband was a British citizen, he returned to Britain, promising to call her over too. He kept his promise. In 1979, she joined him. However, he had led her to believe that she would only be allowed into this country as a visitor, and advised her not to declare their marriage to the immigration officials.

Married life was a nightmare for Rabia. She was beaten regularly, sexually abused, and her movements were strictly controlled by her husband. She learnt that he had been married and had countless affairs with other women before her. The beatings escalated over a five-year period and she was hospitalized on two occasions, the second time whilst pregnant with her second child. It was then that, with the help of a neighbouring couple, she sought the help of the courts to protect herself from further violence. Her husband retaliated by informing the Home Office that she had entered the country illegally, and he then left the country to avoid further court action against himself. The matrimonial home was repossessed by the building society, so she found herself with her two children in bed-and-breakfast accommodation.

This was the situation in which we found Rabia. The immigration officials were making arrangements to deport her. The couple who she thought were assisting her had, in fact, failed to inform her or anyone else of the negotiations, entirely unofficial, that had been taking place between them and the Home Office. One day, they turned up at her bed-and-breakfast accommodation and informed her that the Home Office required her and the two children to report to Heathrow airport that evening to be deported to Pakistan.

Rabia was helped by us to seek immediate legal and parliamentary assistance, and formal representations were made on her behalf to the Home Office. She was finally granted temporary admission, but had to report to a police station every day. Further applications were submitted for her to be granted permission to stay here on compassionate grounds and as a refugee, pointing out the social ostracization, as well as the Zina charge and ensuing punishment, that she faced in Pakistan. The initial response from the Home Office was to say: ‘It is claimed that Mrs Janjua may face imprisonment in Pakistan, but the avoidance of alleged crimes in another country cannot confer upon her any entitlement to remain here’.

The campaign, launched by SBS and later organized by WAF, on behalf of Rabia, was therefore not simply yet another familiar, anti-racist immigration exercise. Perhaps this explains the lack of support we received from a number of the usual antiracist groups and forums. It was also about challenging religious laws, in this case the increasingly Islamized laws of Pakistan, and particularly the Hudood Ordinance of 1979, covering the offence of Zina. We were forced to examine the lives of women in another world. Some of us were forced to understand, consider, rethink our views about ‘internationalism’. The plight of women, particularly from working-class backgrounds, like Rabia, challenged us to understand their position in Pakistan under such laws.

It was in this connexion that we turned to the Women Living Under Muslim Laws dossiers. They proved to be invaluable. We were hungry to know how the Zina and Hudood laws operated in Pakistan, and what the social and political implications were for women living there. Nowhere was the material as rich as that contained in the dossiers. They contained many articles written by women academics and activists in Pakistan on the subject of Zina and the Hudood Ordinance, spelling out how it came into being and its effects on countless women in Pakistan. We were able to present these to the Home Office, Rabia’s lawyers, and MPs as evidence of the risks to which Rabia and her children would be exposed if returned to Pakistan.

Sabiha Sumar and Khalid Nadvi write of the Hudood Ordinance, introduced in 1979 in Pakistan by a promulgation by the then martial-law government, and confirmed on the statute books in 1985:

The background to the Hudood Ordinance lies in the desire of the Pakistani government to bring laws…in conformity with the Quran and Sunnah (the sayings and deed of the prophet). It is an integral part of the much heralded Islamisation process…The Hudood Ordinance deals with the offences of prohibition (consumption of drugs and alcohol), zina (rape, adultery, fornication), theft and qazf (perjury)…Zina is defined as wilful sex between two adults who are not validly married to each other…Both types of zina are liable to the hadd punishment (stoning to death in public) if either a confession is obtained, or if the actual act of penetration is witnessed by four adult, pious and forthright males. Failing this the lighter punishment of tazir (rigorous imprisonment and whipping) applies…The implications arising out of the Hudood Ordinance are severe, and its interpretation by the courts has led to serious miscarriages of justice for women. Whilst zina effectively applies to adultery or fornication and zina-bil-jabr to rape, either by the man or the woman, the onus of providing proof in a rape of a woman rests on the woman herself. If she is unable to convince the court, her allegation that she has been raped is in itself considered as a confession to zina…and the rape victim effectively implicates herself and is liable to punishment. Furthermore, the woman can be categorised as the rapist herself since it is often assumed that she seduced the man.

(Dossier 3)

Sumar and Nadvi go on to show that it is mainly women from poor social backgrounds who find themselves thrown into gaol for the offence of Zina. Women often have no means with which to challenge the sometimes fabricated offences, because they are unaware of the few civil and legal rights they have. The Islamization process has effectively stripped women of their humanity and dignity and denied them their rightful place in Pakistani society.

The information made available to us by the dossiers enabled us to substantiate the threat posed to Rabia if she were to be forced to return to Pakistan. It also educated us on the violation of human rights that occurs in Pakistan in the name of religion. In spite of the election promises of Benazir Bhutto to repeal the Hudood Ordinance, they have remained in existence due to the powerful influence exerted by fundamentalist forces. In fact, the proponents of fundamentalism went further, enacting Islamic Sharia laws, with the aim of bringing all legislative, judicial and bureaucratic decisions in line with the Koran.

We were to take another important political initiative, which was to argue with major Human Rights organizations such as Amnesty International that women such as Rabia, facing what amounted to persecution on the basis of their gender and sexuality, should be included in their criteria of political refugees. We became aware that several Iranian women had tried to seek refugee status on the basis that, as women, they constituted a social group which was being persecuted in Iran under the harsh and extreme antiwomen Islamic laws. Their applications had failed. This compelled us to try even harder to obtain refugee status for Rabia, thereby setting a precedent for other women in similar circumstances.

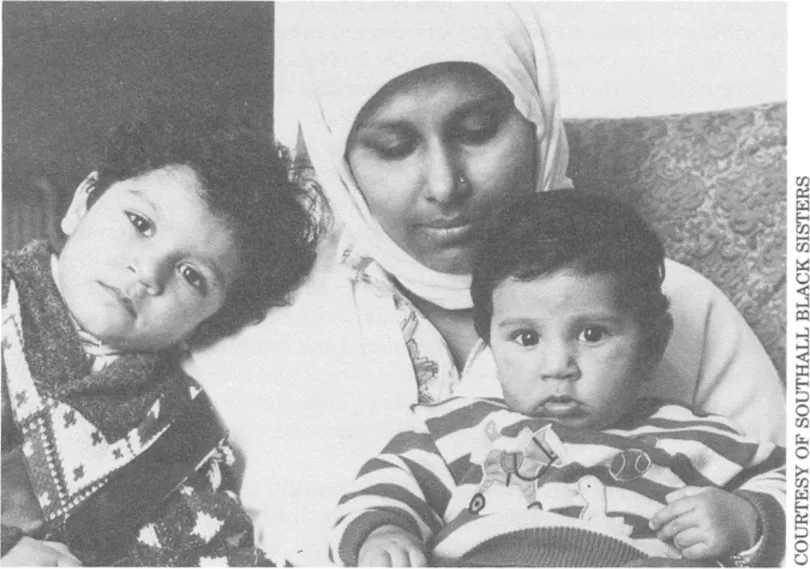

Rabia Janjua and her children

We wrote to the Network of Women Living Under Muslim Laws about Rabia and they immediately responded by writing letters in support of her to the Home Secretary, and supplied us with a list of human rights organizations in Europe. Through their Alert for Action leaflets, which inform women around the world of current campaigns or issues that need to be addressed urgently, they publicized Rabia’s case. They also put us in direct contact with women lawyers and activists in Pakistan, the same women who had contributed articles to the dossiers on Zina, to provide a legal opinion on the political and social implications of Rabia’s situation.

Our links with Women Living Under Muslim Laws were further strengthened when its founder-member, Marie-Aimee Lucas, came to London early in 1990 to try to establish a support group in this country. We learnt that the group was formed in 1984–5 in response to a need for attention to a number of cases that required urgent action, involving women living under Islamic laws or belonging to communities ruled by Muslim religious laws.

The aims and objectives of the group include, amongst others, the creation of international links between women from Muslim countries and communities and between Muslim women and other progressive feminists around the world. The excellent dossiers have been an important channel by which the group has tried to achieve these objectives.

Throughout, the dossiers explain, analyse, publicize and inform us of the struggles of Muslim women in various regimes both secular and religious around the world. They portray Muslim women struggling against the daily inhuman treatment to which they are subjected. The dossiers reveal that women are not merely victims—they are challenging, confronting, questioning and fighting back. We came across the story of an Iranian woman, Ginoos Yaftabadi, whose experiences were alarmingly similar to that of Rabia.

Ginoos was married to an Iranian man and, in May 1986, accompanied him to Japan where he wanted to study. She was eventually abandoned by her husband, who returned to Iran. In the meantime, she had filed for a divorce and entered into a relationship with an American citizen. She also had a child by him. In 1988, the father of Ginoos’s child returned to the States. In April 1989, her Japanese visa expired and the Japanese authorities began to take steps to deport her to Iran. With the intervention of a women’s group, the consequences of such action were highlighted. In Iran, according to the Iranian Civil Code, her divorce would not be recognized and her child would therefore be declared illegitimate. She would be guilty of the crime of Zina which is punishable by death by stoning. The Alert for Action circular in which Ginoos’s case was highlighted goes on to explain that between 1979–85, over a hundred women have been stoned to death, and nearly ten thousand Iranian women were tortured, gaoled or executed by the same regime in the same period. Her application for refugee status in Spain was refused. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees has refused to recognize Ginoos as a refugee.’ (Dossier 5/6)

One of the main objects of Women Living Under Muslim Laws, then, is to ‘increase women’s knowledge about both their common and diverse situations in various contexts, to strengthen their struggles and to create the means to support them internationally from within the Muslim world and outside’ (Dossier 3).

The quality of the information contained in the dossiers is unlikely to be found elsewhere. We certainly doubt whether major human rights organizations catalogue and pull together such experiences of crimes against women. It is all the more remarkable that the dossiers are produced with the aim of not only informing, but acting on aspects of women’s oppression.

We have come to forge a real alliance with Women Living Under Muslim Laws which has fed into many of the struggles in which we are engaged in this country, particularly our refusal to have a single version of the world imposed on us by religious leaders here. In their Introduction to Dossier 3, the issue thumbed through most by us, they write:

It is often presumed that there exists one homogeneous Muslim world. Interaction and discussions between women from different Muslim societies have shown us that while similarities exist, the notion of a uniform Muslim world is a misconception imposed on us. We have erroneously been led to believe that the only way of ‘being’ is the one we currently live in each of our contexts. Depriving us of even dreaming of a different reality is one of the most debilitating forms of oppression we suffer.

(Dossier 3)

This is perhaps the most important message contained in the dossiers and one which we, through our own work in Southall Black Sisters, Brent Asian Women’s Refuge and Women Against Fundamentalism clearly recognize. Many religious women attend our centres, and each brings her own interpretation of her religion, based on her own daily reality and specific experiences.

Religion is a personal matter and should be left to personal interpretation. This is of vital significance, particularly in the context of what Muslim fundamentalists in this country are trying to do. The call for separate schools for Muslim girls, and the reaffirmation of women as the guardians of the home, the private domain, are attempts to curb women’s aspirations and desires beyond their prescribed traditional roles as dictated in the Koran. The project of fundamentalists is to impose one version of Islam and leave no room for interpretation and doubt. Yet there is no uniform interpretation of Islam wherever Muslims live, so why should the fundamentalists seek to impose one now?

For fundamentalists like Kalim Siddiqui, who has recently launched a campaign for a Muslim parliament and manifesto in this country, the issue is not so much adherence to a specific ideology as gaining hegemony by creating a monolithic and homogeneous Muslim community that is easier to control and discipline, with himself and his like as its overall, undisputed leaders. It is about political power. In the process all sorts of dishonest arguments, often co-opted from the antiracist and feminist movements, are used to justify the need to maintain a separate Muslim identity and culture. Their solutions and their concerns are not about addressing racism or the discrimination faced by women. Rabia’s case, for instance, exposed these contradictions clearly. Not one single religious Muslim leader came out in support of the campaign, despite the fact that we were equally critical of the government’s racist immigration policies which compounded her predicament. Instead, we were contacted by a diplomat from the ‘welfare’ section of the Pakistani Embassy, furious that we should expose Pakistani laws in the way we were. No doubt if we had let him talk to Rabia, something he was insistent upon, he would have given her ‘an earful’ and perhaps have attempted to silence her for daring to shame the izzat of her country.

Many women supported Rabia...