![]()

Part I

Overture, Technique, Literature

![]()

Chapter 1

Overture

In view of all that has happened since the foundation of psychoanalysis, surely few dynamic psychotherapists would allow themselves to indulge in the following fantasy:

A method of psychotherapy is developed that is based entirely on psychodynamic principles; it is applicable to a high proportion of nonpsychotic patients; therapeutic effects appear within the first few sessions; and the whole neurosis disappears, so that termination comes smoothly, sometimes within 15 to 40 sessions, or within 70 with some more difficult patients; at termination no trace of the original disturbances can be found; long-term follow-up shows that this position is maintained; moreover, certain adverse phenomena that bedevil traditional dynamic psychotherapy and psychoanalysis—such as regression, intense sexualized or dependent transference, acting out, and difficulties over termination—do not become a problem. Finally, it is possible to train other therapists in the required technique, leading to the hope that the efficiency of therapeutic clinics is greatly increased, and waiting lists are much reduced.

The above passage is adapted from an article that appeared more than 25 years ago, based on observation of the work of Habib Davanloo (see Malan, 1980), and the present book is concerned with evidence that this fantasy has been fulfilled.

The method of therapy was named by Davanloo intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP)—though the duration sometimes goes beyond the usually recognized limit of 40 sessions. The present book is based on the therapy of seven patients treated by Patricia Coughlin Della Selva (PCDS), one of the authors. She was trained by Davanloo but has modified his technique to suit her own personality.

Brevity requires that three of these patients are only briefly summarized in the book, thus dividing the seven patients into four “detailed” (The Man Divided, The Cold-Blooded Businessman, The Good Girl with Ulcerative Colitis, The Woman with Dissociation) and three “summarized” (The Reluctant Fiancée, The Masochistic Artist, The Self-Loathing Headmistress). Nevertheless the latter provide much striking evidence, some of which is presented below and the rest in part III, the General Discussion. In fact little is lost, since all three of these patients have been described elsewhere, as indicated below.

At follow-up (with one possible exception: The Woman with Dissociation, chapter 7), all the original disturbances of these patients had not only disappeared, but had been replaced by what we may call “positive mental health”. This is the empirical definition of “total resolution”.

In order to give a foretaste of the quality of these therapies and their results, we give here vignettes from the three summarized patients.

The Reluctant Fiancée (age 36, 16 sessions, follow-up 8 years): The discovery of commitment and true happiness

This severely disturbed woman (described in Coughlin Della Selva, 1996, pp. 96ff., under the name of “The Woman with Headaches”) went into fugue-like states and became literally paralysed with fear at the very thought of marriage. In addition, she suffered (1) from lifelong depression with strong suicidal impulses; and (2) from headaches, at least once a week, which were so severe that she had been repeatedly hospitalized from the age of 8 years to the present time.

In her background she had been exposed to systematic physical and sexual abuse by her father, from which her invalid mother had never been able to protect her.

The criteria for resolution of her problems, formulated by two judges blind to the events of therapy, included: “Loss of all symptoms” and “To have a warm, satisfying, and committed relation with a man who reciprocates. To be able to accept and give love and tenderness without reserve.”

The main issues in therapy were: murderous rage against her father, followed by love; rage against a previous boyfriend; anger and love towards her mother; and grief about what she had missed in childhood.

At 8-year follow-up, she said: “I don’t have any of those symptoms any more—it’s a distant memory.”

In connection with her problem over commitment, she spoke as follows:

“Something amazing happened. Once I walked down the aisle there’s been no looking back. It was as if I was crossing a bridge from my old life into a new one. I saw him standing there at the altar, and suddenly a feeling of peace and happiness came over me. Now I am happier than I ever imagined possible. I just love being married. I have the family I always wanted and never had. It’s the same for my husband. We had a foundation of tenderness and trust. From that, passion emerged.”

The Masochistic Artist (age 39, separated, 32 sessions, follow-up 4 years): The discovery of sexual closeness

This patient (described in Coughlin Della Selva, 1996, pp. 161ff) was complaining of depression, anxiety, and guilt, which were precipitated by leaving her abusive husband.

She had never been able to reach an orgasm with a man and could only do so with fantasies, dating from the age of 6 years, of being raped and tortured.

The criteria for true resolution of her problems—formulated as before by two judges blind to the events of therapy—included: “To find a man who respects and loves her, with whom she can form a mutually fulfilling relation”; and “Disappearance of her masochistic sexual fantasies, with the ability to enjoy loving sex.”

The main issues in her therapy were anger against her father for sexualizing the relationship with her; anger and grief about her mother’s physical abuse and lack of caring; and mourning for her mother’s death.

At 4-year follow-up, she had a relationship with a new man who treated her kindly, and the masochistic fantasies had entirely disappeared. She made the following remarks about their sexual relation: “I love his body and he delights in mine. It’s an enraptured sense of this other being. I guess what’s different from before is that the desire is for him as a person, which is expressed physically and sexually.”

The Self-Loathing Headmistress (age 29, 58 sessions, follow-up 5 years): The discovery of joy

For this married woman (described in Coughlin Della Selva, 1992), all pleasure in life had been destroyed by a state of self-loathing and selfpunishment. She was afraid to have children.

Her mother, who clearly wished she could have got rid of her, seriously and deliberately neglected her. The patient lost the warm relationship with her father at puberty.

Criteria included the following: “Loss of self-hatred and self-punishment, with a major increase in her capacity to enjoy life. We would like to see her enter motherhood with confidence and enjoy her children.”

The main themes of therapy were anger with both parents and identification with her mother’s hatred of her.

At 5-year follow-up she recounted the following incident:

She and her 5-year old daughter had been watching a videotaped play in which a young girl was left alone and bereft after the death of her mother. The patient said: “She looked at me as if she would take me in with her eyes and keep me inside her. She said, ‘I will love you when you’re dead’. Wow! She’s only five! What was I to say? Well, I said—and even though I don’t know what it means—‘I’ll love you, even after I’m dead”. And she cried and cried. And I just held her, and it was a moment of such profound joy, just beyond the limits of this universe, beyond words.”

This unforgettable moment was experienced by a woman who, before therapy, could feel nothing but self-loathing.

We hope these vignettes speak for themselves.

We write as scientists, and the question may well be asked: What has science to do with concepts such as emotional closeness, happiness, or joy? Our answer is that if the science of psychotherapy cannot deal with these concepts, then it can only be concerned with superficialities and irrelevancies. If we do use them, then all that is needed is that the evidence on which they are based should be published in full.

The Aims of This Book

The following are some of the principal aims of the work presented here: to describe with examples how these extraordinary therapeutic results can be achieved; to help to instruct the reader in how to do it; to survey the literature confirming the efficacy of dynamic psychotherapy through randomized controlled trials; and to show how each element in the technique is supported by objective evidence, including that from neurobiology.

This is not all. We show how these therapies unmistakably confirm, with detailed evidence from videotaped interviews, many of the concepts and principles of dynamic psychotherapy. In addition, we have tried to introduce as much science into the study of these therapies as the subject can bear—neither too much nor too little. The initial interviews or “trial therapies” conducted by PCDS are routinely so deepgoing that it is possible for judges blind to the events of therapy to make accurate formulations of the patients’ problems and their origin, and to lay down the criteria that would indicate that the neuroses had been truly “resolved”. These criteria are then matched against the findings at follow-up, which makes potentially highly subjective judgements far more objective.

We have also explored the possibility of predicting the main issues that would be dealt with in therapy and that would lead to therapeutic effects, thus trying to convert each therapy into a scientific experiment.

The Relevance to the History of Psychotherapy Research

By now it is generally accepted that there are three primary sources of evidence for the efficacy of psychotherapy: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), studies of process, and studies of individual patients.

RCTs have always been regarded as the “gold standard” of research in psychotherapy, but they have serious limitations. Chief of these is their reliance on averages, together with “objective” outcome criteria, which reveal nothing about the true quality of the therapeutic results or about the distribution of scores for outcome in the experimental and control series—suppose, for instance, that in spite of the averages being essentially equal, the “best” results are clustered together in one of the two samples rather than in the other? Mental health practitioners need data on individuals, not groups, and in particular they are interested in knowing how (and if) improvements occur during a series of therapeutic interventions. Furthermore, practitioners need to know what particular interventions are followed by therapeutic effects. For these purposes, process research and studies of single therapies (N=1 studies) are required.

For many years there has been a recurrent theme in the literature—insufficiently heeded and with very little influence—consisting of disillusion with RCTs, because of their questionable relevance to clinical practice, and a corresponding advocacy of N=1 studies. This goes back to the 1960s, when it was expressed even by some leading researchers who had devoted their lives to “gold-standard” RCT studies, represented by Carl Rogers, Allen Bergin, and Arnold Lazarus (see Bergin & Strupp, 1972, and a review by Malan, 1973). Interestingly, this situation was exactly repeated in the 1990s. The following is a single illustration chosen from many: Safran and Muran (1994) reiterated Bergin & Strupp’s criticisms of RCTs and wrote: “There is an important need for more intensive analysis of single cases in order to yield clinically useful information.”

Now, in the 2000s, this view is gradually coming into its own. It is represented by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), which has “re-written nearly all its funding announcements to reflect the change in priority from large scale clinical trials in controlled settings, to research designed to study large numbers of diverse patients in real-world settings . . .” (Foxhall, 2000).

More recent spokesmen for this trend are Ingram and Mulick (2005), who write in a letter to the Editor of the APA Monitor on Psychology that, in addition to RCTs, at least two other methodologies “deserve to be included as part of the pillar of empirical validation”. One is qualitative research involving the study of small groups of patients, and the other consists of “single-case design methods in clinical practice, through which an appropriate treatment is empirically validated for a unique client, not for groups of patients who share a diagnostic label”. This is both encouraging and discouraging. It is encouraging that such a view is being expressed; yet it is discouraging that, instead of just being universally accepted and acted on, it still has to be expressed. We—quite independently—have seen this need, and the present book is a response to it. We are also responding to what Lazarus advocated in his interview with Bergin and Strupp (1972)—namely, the study of “patient– therapist pairs in all their complexity”.

An important theme running through these studies is that sometimes it is possible to demonstrate the effectiveness of a method of psychotherapy beyond all reasonable doubt, without the use of a control series. This applies in the following circumstances:

- The patients have suffered from crippling symptoms and other severe disturbances (e.g. self-destructive behaviour patterns, grossly unsatisfactory human relations) for many years, often since childhood.

- In some patients, years of previous therapy, both dynamic and nondynamic, have failed to produce improvement.

- Patients are taken into ISTDP and begin to show major improvements within the first few weeks, and at termination they show complete recovery. No relapse occurs during a follow-up period of many years, even when the patient is subjected to severe stress (e.g. see The Good Girl with Ulcerative Colitis, chapter 6).

- Careful records, taken from videotapes, show that improvements began immediately after certain types of event in therapy, particularly the de-repression of buried feelings of grief and anger about people in the patient’s early life.

- These feelings are experienced with such intensity as to leave no doubt of their significance.

- The connection between the patient’s disturbances, on the one hand, and the buried feelings, on the other, can be clearly inferred.

Under these circumstances, even the most determined sceptic would find it hard to maintain that the improvements were due to “spontaneous remission”, which just happened to occur during a period when, by coincidence, the patient was being treated with dynamic psychotherapy.

All these conditions were fulfilled by the seven therapies with which this book is concerned.

The Importance of Studying Outcome

Finally, it is worth saying that one of the main emphases throughout this book is on the extremely detailed and psychodynamically based examination of outcome—that Cinderella of psychotherapeutic variables, so inadequately studied in the literature.

![]()

Chapter 2

Introduction to the theory and technique of Davanloo’s ISTDP

Theoretical Underpinnings

The techniques used throughout this book were developed by Davanloo (1980, 1990, 2000) and evolved from his understanding of the psychoanalytic theory of neurosis (Fenichel, 1945). In particular, Davanloo based his strategic interventions on Freud’s second theory of anxiety (Freud, 1926d [1925]. This theory suggests that anxiety is a signal to the ego, warning of danger or trauma; “danger” here is any feeling, impulse, or action that could threaten the primary bond with caretakers. In other words, any feeling, impulse, or action that results in separation from a loved one, or the loss of his or her love, is experienced as threatening, evokes anxiety, and is consequently avoided, giving rise to intrapsychic conflict between expressive and repressive forces within the psyche.

The two triangles

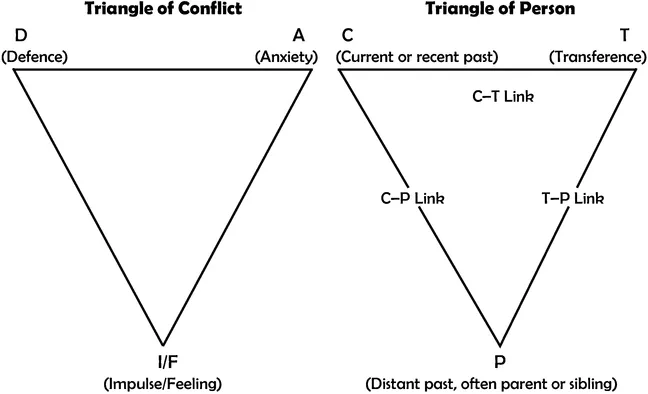

The Triangle of Conflict

This dynamic conceptualization of conflict can be depicted in operational terms by the Triangle of Conflict (see Figure 2.1, left). At the bottom of the triangle are the core emotions. When the expression of these emotions results in negative interpersonal consequences, they become associated with the aversive states of anxiety, guilt, and shame and are avoided via the use of defences (for more detail, see Coughlin Della Selva, 1996, pp. 6–7). The Triangle of Person (Figure 2.1, right) was added to the Triangle of Conflict (by Malan, 1979) in order to depict the interpersonal nature of human experience and emotional expression. What begins as an interpersonal interaction becomes internalized in the form of an intrapsychic conflict over time. In other words, if a child is consistently punished for the expression of anger, he will begin to get anxious when angry and will learn ways to avoid its expression. Let’s say that passivity and withdrawal become the child’s strategies of choice for avoiding the experience and expression of anger (and its feared consequences). Eventually, he may retreat to this position so automatically that even he is unaware of feeling angry inside. The defences come to replace the feeling itself and can result in character pathology (e.g., passive aggressive or avoidant personality disorders), affecting all future relationships.

FIGURE 2.1. The two triangles

The Triangle of Person

The Triangle of Person (Figure 2.1, right) depicts the way in which conflicts involving core emotions get over-generalized, affecting patients’ interactions with others in their current life, including the therapist.

The use of the two triangles aids the therapist in organizing the patient’s material and serves as a guide to intervention. For example, if

the patient arrives to his therapy session with anxiety, it is a signal to the therapist that some threatening emotion is being experienced, in all likelihood towards the therapist. This theoretical understanding guides therapeutic interv...