eBook - ePub

Recovered Memories of Abuse

True or False?

Peter Fonagy, Joseph Sandler, Peter Fonagy, Joseph Sandler

This is a test

Share book

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Recovered Memories of Abuse

True or False?

Peter Fonagy, Joseph Sandler, Peter Fonagy, Joseph Sandler

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

These papers - from a conference with the same title - includes work by Lawrence Weiskrant (highlighting the concerns around false memories), John Morton (outlining contemporary models of memory), and Valerie Sinason (on detecting abuse in child psychotherapy). The second half presents a psychoanalytic theory of false memory syndrome, by the authors then offer a final overview.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Recovered Memories of Abuse an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Recovered Memories of Abuse by Peter Fonagy, Joseph Sandler, Peter Fonagy, Joseph Sandler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Chapter One

Memories of abuse, or abuse of memories?

The topic of recovered memories of abuse is of considerable social importance, and of personal concern—indeed of grief—to many individuals. But perhaps I should first say what I consider that this discussion is not about.

There are many interesting issues about which it is not. It is not about whether sexual abuse occurs: it does, and the consequences can be dire. Estimates of how frequently it occurs in our society might be relevant for judging base rates, but I shall not deal with such estimates, nor with the very difficult and fuzzy question of definition. It is not about whether satanic ritual abuse occurs. No one has yet provided any convincing and concrete confirmative evidence, here or in America, that it does in detectable frequency (viz. the report by Lanning, 1992, in the United States and by La Fontaine, 1994, in the United Kingdom). But no one can prove the universal negative—that is, prove that it never does occur nor has occurred. Exhortation that it might occur does not get us very far. Nor, equally, can one prove the universal negative about abuse by alien visitors from outer space, nor of the recovery of memories of earlier lives. Nor is my talk about the sincerity or otherwise of beliefs of therapists, although Yapko’s (1993) findings that 28% of a large population of graduate therapists in the United States believe that hypnosis can resurrect memories from past lives, and that 53% of them believe that it can retrieve memories going back to child-birth, are, to put it mildly, rather disturbing. We do not know the comparable figures for this country, and it was hoped that the British Psychological Society (BPS) would provide such evidence in its report (Morton et al., 1995). (In fact, the published report does not pursue such points, and, alas, I found the report itself to be weakly complacent in its outlook and deeply unsatisfactory in its analysis: for a critique see Weiskrantz, 1995.)

It is not about children’s testimony, about which there is now very disturbing and important experimental evidence by Steven Ceci and colleagues (Ceci & Bruck, 1993). Nor is it about the character, or the assassination of character, of any of the leading protagonists in the debate for and against false memories.

Finally, it is not about the sincerity and mental anguish of those who truly believe their memories of alleged abuse, nor is it about the anguish of those patients who equally sincerely fiercely deny the accusations.

What it is about is “recovered memories”—that is, memories of alleged abuse that surface after periods, usually of several years, of complete amnesia for alleged events. Usually, but not always, such recovered memories arise after exposure to particular therapeutic regimes. What evidence, if any, can one bring to bear upon the truth or falsity of such recovered memories, and what is their status in terms of what is known about memory mechanisms from the scientific study of the field of memory? These are the questions to be addressed. The issues will not be settled by a show of hands or a popularity rating of whether 8 out of 10 cats prefer a brand of cat food, or how many therapists equal one anthropologist. We need evidence, and above all we need to be clear about when in principle there is no evidence and even can be no evidence.

One reason for the current interest in the phenomenon of recovered memories is sociological, and no doubt there will be sociological post-mortems of the phenomena for years to come. We are witnessing a social epidemic. In America, in just two or three years, something like 10,000 families have claimed to be the victims of false accusations; in the United Kingdom, in one to two years, something like 350 families. No doubt one reason for this epidemic is the belated realization that childhood sexual abuse (CSA) does occur in Western society, and the social strictures or shame of acknowledgment of this in individual cases are being relaxed. The abused can come out into the open. Equally, there is no doubt a belief, which many have likened to the witch-hunts of old, that abusers abound and that they must be winkled out. This is, unfortunately, held together with a belief among many that practically any type of difficulty of personal adjustment, be it an eating disorder, or arthritis, or a particular style of clothing—the list is endless and extremely democratic—can be traced back to early sexual abuse, whether or not it can be remembered at first by the individual concerned.

The demographic data about the American families paints an interesting, at first surprising, prototype of both accusers and accused, based on questionnaire responses obtained (Freyd & Roth, 1993). Of the accused parents, 92% were over 50 years of age, were predominantly in the upper- or middle-class economic category, and were well-educated (40% university graduates). The accusing children were not youngsters—50% of them were between 31 and 40 years of age. One-third of these children’s memories were said to have been repressed for twenty to thirty years, and almost another third for thirty to forty years. Half of the claims were of abuse said to have taken place before the age of 4 years, and a quarter of the claims were to events before the age of 2 years. More than half of the allegations were of “many episodes” of abuse.

Demographic data for the U.K. families is in the course of being collected, but, at the first meeting recently in London of about sixty pairs of parents, they appear to be very similar to the American prototype—middle-aged and middle-class, and their accusing children quite mature and, on the whole, well-educated. In the majority of cases, the accusing children had broken off all relations with the parents after making the accusations, sometimes of quite horrendous character, and the therapists’ identities were kept secret. Somewhat alarmingly, a large number of the parents raised their hands in positive response to the question of whether their children were training to become therapists. This is not my topic, but how can anyone condone the deliberate breaking off of long-developed bonds of support, deliberately casting clients adrift in anger, creating new victims in the course of doing so, and yet claim to be a responsible therapist?

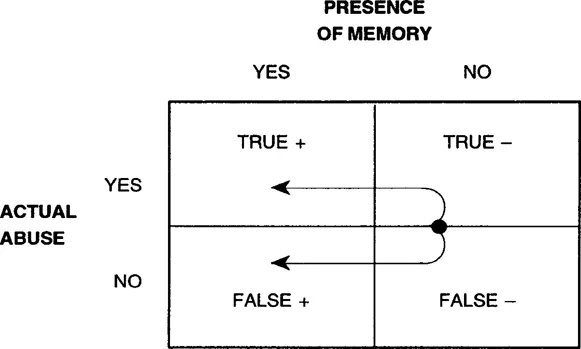

The situation, from a logic point of view, of recovered memory after amnesia is something like the diagram shown in Figure 1. Before the recovery, we do not know whether there was or was not genuine abuse historically, so the supposedly unrecovered information is placed in a neutral position between a false negative and a true negative. The decision is what status to assign to it when it becomes described by the accuser as a genuine memory: is it a true-positive memory or a false-positive memory? The crux of the argument is that the accusers and their therapists are claiming that a false negative becomes a true positive, whereas the False Memory Society parents—who insist on their innocence—are claiming that a true negative becomes a false positive. Both parties can be, and we must assume usually are, absolutely sincere. We cannot settle the matter by a show of hands or even by a lie detector.

Nor can the issue be settled by theoretical argument or by exhortation; both the upper and lower routes (Figure 1) appeal to mechanisms that could account for the switch from amnesia to “recovered” memories, whether true positives or false positives. The best-known claim of the upper route—from false negative to true positive—is for a dual mechanism, and both parts are necessary: (1) that the memories of the horrible and traumatic events were repressed, and (2) that they later became unrepressed, usually by particular procedures with special effectiveness for unrepression. Both of these require a bit of examination. First, what about repression as a mechanism? Here the arguments run rampant between those who claim it to be a powerful and often-demonstrated clinical phenomenon, and those (e.g. Ofshe) who deny its existence and assert just as strongly that there has never been a shred of evidence to support its existence. I believe that repression is a hypothesis—by its nature not a demonstrable fact. That there is real loss of recall, or even of recognition of past events, whether horrible, or even pleasant, or just neutral, is ubiquitous. No one doubts this. We know something of the factors that determine forgetting, such as encoding specificity, proactive and retroactive interference. We can also grant that the memories of some events are not lost, but are simply evaded out of embarrassment—such as when I avoid thinking about some dreadful faux pas I have made. What is a theoretical and not a factual issue is: when is loss of information forgetting and when is it repression? I know of no criterion that allows us to say when forgetting, which is a fact, should be classified as repression, which is a concept.

FIGURE 1

Still on the issue of the first mechanism of the pair, “repression”, it has been argued that certain types of events, extremely painful or horrible or traumatic, cannot be tolerated and are robustly or actively buried. The supposition is, presumably, that these events would normally be super-memorable because of their intensity and emotional quality, but are so strong that they cannot be tolerated by the subject. Here the issue is complicated. Most survivors of traumatic events, of concentration camp horrors, for example, have the opposite difficulty—they cannot forget, rather than being unable to remember. Admittedly, details are lost or simplified or amplified or otherwise recast, just as with normal forgetting, and sometimes this is just because the respondents are by now growing old, but there is not a loss of what Henry Head called the schema, or the general scenario. There are attested cases, however, of memory loss, so-called “functional amnesias” following trauma, such as the death of a loved one or a rape. These have been usefully reviewed in a sophisticated article by Schacter and Kihlstrom (1989). Typically, a traumatic functional amnesia is characterized initially by a fugue state, with amnesia for events occurring in the fugue state itself. In a second stage, there may be recovery from the fugue state but a loss of personal identity and considerable retrograde amnesia. In the final stage, after patients have recovered their identity and personal past, the events of the fugue state still remain lost but the initial events may have returned. It must be borne in mind that these are necessarily retrospective clinical descriptions—one cannot predict in advance when one is going to have an occasion to exhibit functional amnesia! Typically, by the time the third phase has been reached, the subject has repeatedly been put through recaps of his or her own life and circumstances ad nauseam by clinicians, friends, and family keen to restore the person to normality. How much is genuine retrieval of the original event, as opposed to new knowledge, must remain in doubt.

These are fascinating phenomena about which knowledge is still quite modest; they are not the typical scenarios in the cases of so-called recovered memories. The third stage of the functional amnesia, when memory returns, is not twenty or thirty years after the event but much sooner. Also, the events during the fugue state remain lost, whereas in the recovered memory cases masses of material both before and after the events, some of it astonishingly detailed, are reputed to be accessed. Finally, the fugue state is sufficiently enduring to be noted by parents, teachers, and other observers, whereas the cases of recovered memory do not come typically with such documentation of a prolonged clinical stage at the time of the alleged events, and especially are notably absent when the abuse is said to be have been repeated over several years, thereby requiring the generation of a functional amnesia for each episode. Aside from the ever-present problem of simulation of amnesia, there is a further possibility, which Ofshe and Watters (1993) raise as a suggestion—namely, that the traumatic functional amnesias are genuinely due to blackout similar to an alcoholic or other toxic state, or extreme fatigue as in the soldiers studied by Sargant and Slater (1941), sufficient to cause disruption of the biochemical process of memory storage itself. In that case, there will be a genuine loss of the laying down, the consolidation of long-term memory. By definition, a failure of consolidation is itself irreversible, or at best only partially reversible with permanent loss of detail or with confused detail.

We still have considered only the first phase of the dual mechanism proposed by repression theorists—the occurrence of amnesia. What about the second phase, the supposed undoing of the amnesia? One of the underlying assumptions regarding the recovery is also taken to bolster the repression interpretation of the amnesia itself: that there are special privileged routes into the repressed domain which can reveal its content. Of these, hypnosis is the most common, but also “truth drugs” such as sodium amytal—or it can be image analysis, or dream analysis, or, of course, the free association methods of classical psychoanalysis. Here we can be dogmatic. No one now accepts that there is any evidence that hypnosis or amytal treatment reveals memories of past events that are any more accurate than normal methods of recall. Indeed, the evidence is to the contrary: that its accuracy is typically less good, although the subject’s confidence may be much higher for material supposedly dredged up in hypnosis. Much more seriously, these methods depend directly upon the increased suggestibility of the subjects when they are in such states, when new beliefs can be injected that are remembered as real events. In any event, the courts have long refused to admit evidence based on hypnosis, and the use of sodium amytal in the Gary Ramona case (see Chapter 2) highlights the doubt that experts and the courts cast upon this technique. There may be methods of obtaining better retrieval of stored information. But there is no royal or privileged route to the historical truth of the original events through the dredging up of subjects’ utterances in these suggestible states. I believe this a point on which all authorities are in agreement, such as John Kihlstrom in the United States (Kihlstrom & Bamhardt, 1993) and Peter Naish (1986) in Britain, to name but a few.

If one considers normal mechanisms of forgetting, in contrast to a mechanism of active suppression or repression, then it has to be said that the prototypical examples of recovered memory simply do not fit the evidence from research of normal memory mechanisms in at least two respects. Firstly, the amount of graphic detail, extending in 10% of the U.S. cases to claims of bizarre satanic ritual abuse, supposedly recalled from events that allegedly took place twenty or thirty years earlier, is in stark contrast to the fragmentary, patchy evidence of long-term episodic memories going back that far. Normal memory is not like that. Secondly, over half of the memories relate to the period of infantile amnesia, which no one—I repeat, no one—has ever been able to reverse with evidence that bears close examination. The mean period of the end of infantile amnesia is about 4 years of age. Even allowing that there are some claims, themselves controversial, of the retention of episodes back to 2 years of age, recovered memories claiming to be of happenings at a few months of age, which are not uncommon in the recovered memory repertoire, are simply unbelievable. I shall say something later about possible research into the phenomenon of infantile amnesia that might be relevant to future developments, but here I just highlight this clear disjunction between recovered memories and other memory phenomena. Of course, it might be that these species of recovered memories were to have been found throughout history but not reported, but it does seem strange for there to be ten thousand of them in two or three years against a history of striking paucity before that time.

But let me take you back to evidence—or, more strictly, to its lack. In the thousands of prototypical cases reported, I have not come across a single instance of a genuine and reliable corroboration that stands careful scrutiny, independently recorded at the time of the alleged abuse. This may be my ignorance, but if there are such examples of corroboration, they must be relatively rare. This is not to say that the remembered abuse did not occur, simply that we do not know. Instead of evidence, much of the conviction stems not from fact, but from a hypothesis of repression, whose content is by definition unknowable, and reinforced circularly by a further hypothesis of the presumption, not a demonstration, of abuse to account both for the repression and for its reversal, completely without scientific or empirical evidence. Those within this charmed logical circle appear not to be moved or embarrassed in the slightest by the absence of such evidence.

But, in the end, we cannot with certainty say that they are necessarily wrong, especially as some of the proponents argue that such memories are especially linked to events that are shameful—although even there the shame would have had to be added later, since babies do not normally react with shame to having their nappies changed and their genitals cleaned. Recovered memories having these claimed properties do not fit with what we know about memory, especially if they are taken to reflect early infancy or even birth, but science is full of strange and unexpected discoveries, as my own research has taught me over and over again. So let us leave it as strange but—as with all universal negatives—beyond disproof.

Let us turn to the arguments on the lower route, via the true-negative memory to the false-positive memory. Is there evidence for the generation of mistaken memories, and if so, how do they arise? It is obvious that we must be talking about long-term memory and, technically, about what is known as episodic or event memory, about which more later. Here evidence abounds. I will start with a few anecdotes, because they concern well-known psychologists confessing to being embarrassed by just this phenomenon (I am indebted to a correspondent, Dr Kilroy, for these).

The famous child psychologist Jean Piaget clearly remembered his nanny’s fighting off a man who tried to kidnap him from his pram. He even remembered the scratches that she received on her face during the battle. When he was 15 years old, the nanny wrote to Piaget’s father and confessed that the story was a complete fabrication; she had been converted to the Salvation Army and now wanted to confess all her past faults. She even returned the watch that Piaget’s father had given her as a reward. Of course, perhaps the Salvation Army might have generated a false memory in her!

Another account is of Alfred Adler, who clearly remembered his fear as a child when he had to walk past a cemetery on his way to school. None of his schoolmates was in the least frightened, however. So, to train himself to overcome his fears, he remembered forcing himself to run over the graves until he had conquered his fear. At age 35 he returned to his home town and went to visit the cemetery. But there was none. There never had been one.

Even those clearest memories that we are reputed to have, the so-called snapshot memories, can include false material. Another we...